Scientist saves ferrets from extinction… with sperm

By Greta Johnsen

Scientist saves ferrets from extinction… with sperm

By Greta Johnsen“They call me sperm girl,” Rachel Santymire says with a smile.

She’s standing in her lab at the Lincoln Park Zoo, where she’s the Director of the Davies Center for Epidemiology and Endocrinology. She’s been studying sperm preservation since graduate school.

Next to her is a microscope, where slides of dead sperm are already prepared for a demonstration. The table is clean, with just a few framed pictures— one of some black-footed ferrets, one of prairie dogs, and two of sperm.

Santymire says she’s always loved the black-footed ferret. Native to North America, the carnivore fills an essential role in the prairie ecosystem, eating prairie dogs and living in their burrows.

By the 1980s, there were only 18 black-footed ferrets left in the world, so conservationists rounded them up and tried to breed them in captivity.

But despite their best efforts, the species just wasn’t viable— and that had a lot to do with the black-footed ferrets’ sperm.

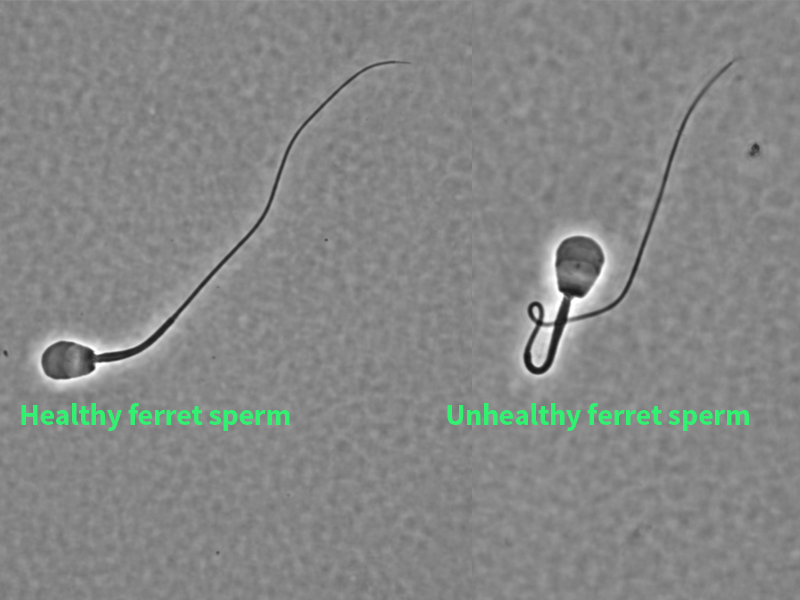

Santymire shows me a sample in her microscope, pointing out the virile, hydrodynamic swimmers and the malformed, tangled flounderers. For some reason, Santymire says, the offspring of those original 18 ferrets had high percentages of inefficient sperm, which made it nearly impossible for female ferrets to become impregnated.

But luckily, scientists had saved sperm samples from Scarface, one of the original 18 ferrets. He’s long dead now, but his sperm, which is much more virile than his offspring, lives on, frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Santymire says scientists had always assumed it was possible to freeze and re-animate sperm— but it wasn’t until she tried it with Scarface that the process worked.

“We were able to take semen that had been under liquid nitrogen for 10-20 years and then thaw it, use it for artificial insemination, and we’ve had eight babies born from that,” Santymire says.

And the implications are significant.

“Because we’ve been able to do this with the black footed ferret,” Santymire says, “we are sort of the model species for future endangered carnivore and other species.”

Greta Johnsen is a reporter and anchor at WBEZ. Follow her @gretamjohnsen

Photos courtesy Lincoln Park Zoo