Should ban on mandatory life without parole encompass old juvie cases?

By By Linda Paul

Should ban on mandatory life without parole encompass old juvie cases?

By By Linda PaulIn the summer of 2012, in a case called Miller v. Alabama, the U. S. Supreme Court ruled that mandatory life without parole sentences for juveniles are cruel and unusual punishment, and therefore unconstitutional.

The key word here is “mandatory.” In the 1980s and 90s there was a lot of talk about young “super predators” and almost every state enacted tougher punishment for juveniles who committed violent crimes. Illinois was no exception.

The Supreme Court said that mandatory sentences don’t let a judge consider extenuating circumstances such as the person’s age, home life, how involved he was in the crime, and the potential for rehabilitation.

But the decision didn’t entirely rule out life without parole sentences for juveniles—though the Court said they should be used only sparingly.

Thorny legal question

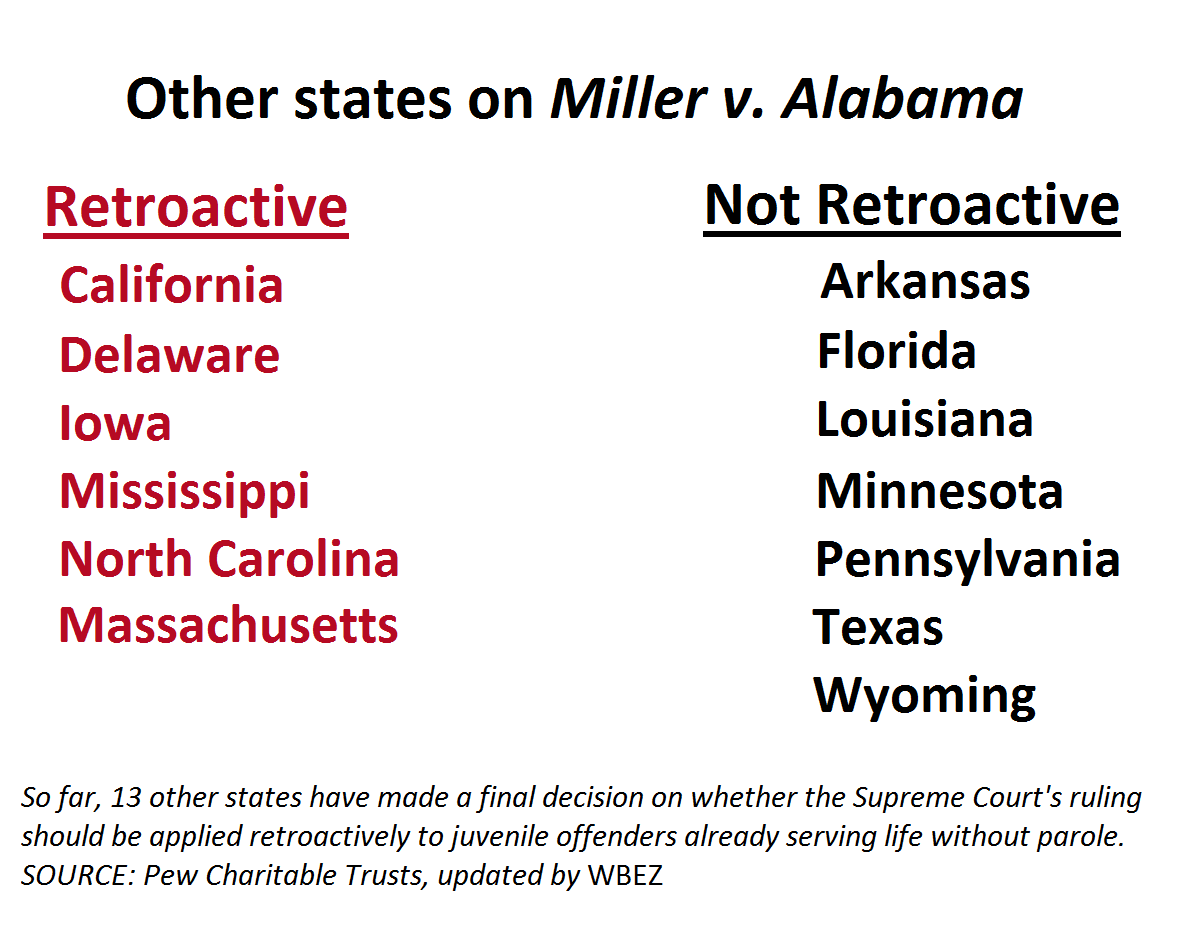

In its wake, Miller has raised a thorny legal question: Should it also apply to people in prison who as juveniles received mandatory life without parole sentences but now their appeals are over, and their case is closed?

The question has come up because several such people have requested new sentencing hearings. And Illinois’s Appellate Court, citing the Miller decision, granted at least five of them – unanimously.

One of those five people is Addolfo Davis. Davis was arrested two months past his 14th birthday and he’s never seen the streets since.

Today he’s 37 and has spent almost two-thirds of his life behind bars. It’s Addolfo’s case that will be presented in oral arguments today, January 15, before the Illinois Supreme Court.Patricia Soung, who will represent Davis, tells WBEZ that on the night of his crime he went with two older co-defendants, at their instruction, to rob an apartment.

“Two people were shot and killed that night by the two older co-defendants,“ she tells us. “Davis was convicted of double homicide as an accomplice,” she says, and ultimately received a mandatory life without parole sentence.

The lawyers won’t just be arguing the facts of the Davis case this day. They’ll also debate whether Miller v. Alabama is so ground-breaking that it should apply to cases that are already settled.

Patricia Soung explains that “the United States Supreme Court created two categories of rules that should be applied retroactively – ‘substantive’ and ‘watershed’ rules of criminal procedure.”

In her opinion Miller is so sweeping that it falls into both categories.But not everyone agrees.

High bar

How exactly the court differentiates substantive from watershed is complex and open to interpretation.

I’m not the only one who thinks these definitions can get murky.

Matt Jones, associate director of the Illinois Office of the State’s Attorney, Appellate Prosecutor, thinks so too.

“It’s a sort of, I know it when I see it,” he says, talking about whether a rule rises to a level worthy of being considered retroactive. “Can we have a fair criminal justice system without this new procedural change?” Matt Jones asks. “If we can’t — then it’s the kind of rule that has to be applied retroactively.”

However. If we can have a fair system without the change, he says, it’s something that should be implemented moving forward to improve the system “but not something that we should necessarily go back and undo every case that has been done,” he explains. “Even if there are questions about whether each and every case was fair.”

Jones says the U.S Supreme Court almost never considers a new rule earth-shaking enough to actually do this.

“And I will tell you that the only instance that they’ve ever cited as an example of that was Gideon – the right to counsel.”

Counsel, that is, for defendants in criminal cases who couldn’t afford to pay for an attorney. That seems like a rather high bar. One that Miller doesn’t reach, according to many prosecutors across Illinois. I asked Patricia Soung if she’s worried that the Miller decision isn’t significant enough to meet that standard.

Turns out, she’s not.

“Gideon provided due process where none existed before and Miller does the same thing,” she says. “It gives you counsel where you essentially had no counsel at sentencing. The proceeding was made hollow because you were denied an opportunity to have your counsel present, mitigating factors in the same way as in Gideon a defendant without counsel had no opportunity to provide an adequate defense. So in both cases we’re talking about providing due process where no due process existed at all.”

Introducing the possibility of re-sentencing hearings for juvenile life without parole cases from long ago introduces a difficult problem. There could potentially be hundreds of victims and first-hand witnesses who’ve been assured that the perpetrators are imprisoned for life.

“Not only are the family members dragged back through this process,” Matt Jones explains, “but now key witnesses who depended upon this certainty that a conviction means a conviction, that life means life— are now going to have be dragged back potentially through the process. Now with a re-sentencing you may not have to have those key witnesses come back, but their lives are similarly put on pins and needles awaiting the outcome of this person getting out. And life doesn’t necessarily mean life for those witnesses.”

These are gut-wrenching concerns, and so the Illinois Supreme Court will be venturing into complicated and emotional territory.

Court watchers expect a decision by the summer.

Clarification: While today’s oral arguments were pending, Cook County State’s Attorney Alan Spellberg declined WBEZ’s request for an interview. With permission from the Cook County State’s Attorney’s office, WBEZ used tape of Spellberg from an interview conducted in March of 2012 whrn we were preparing a story about Addolfo Davis’ bid for clemency.