The Comics: From Page to Stage

By By Jonathan Abarbanel

The Comics: From Page to Stage

By By Jonathan AbarbanelAlthough not based on a comic book or a comic strip, the new musical Hero at the Marriott Theatre in Lincolnshire revolves around a father-and-son who own a comic shop in Milwaukee, where the son—himself a gifted artist—records his ho-hum life in his sketch book as if he were the hero of a graphic novel. You don’t actually learn much about graphic novels or superhero comics (except that Blackhawk is the richest superhero), but the context got me to thinking…

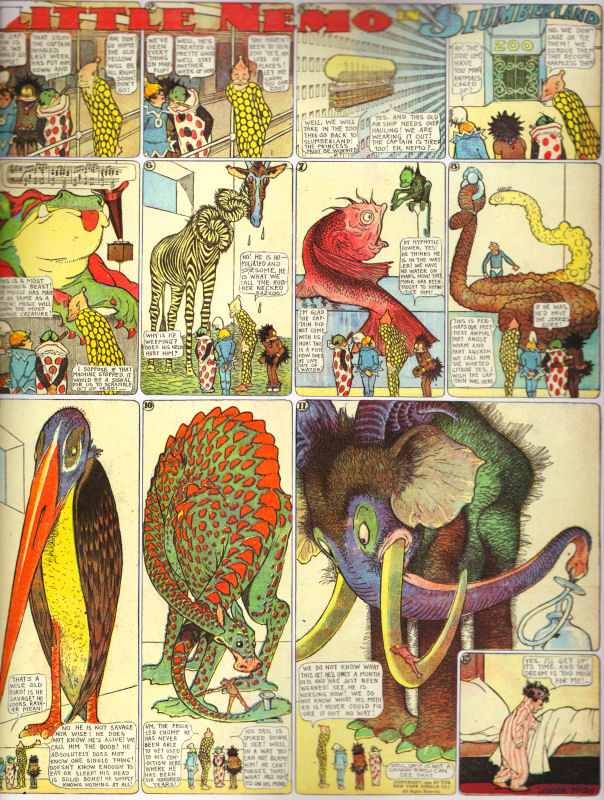

But the history of theater and comics goes back at least to 1908, when a Broadway hit of the season was the musical Little Nemo, with a score by Victor Herbert, based on the wildly popular fantasy comic strip (then in the New York Herald), Little Nemo in Slumberland, written and drawn by the great Winsor McCay (also a pioneer of animated films).

In between, there have been such musicals as It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane, It’s Superman, Annie and Annie II, You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown and The Addams Family, based on the single-panel cartoons of Charles Adams. Also, there was The Mad Show, a 1966 Off-Broadway precursor to Mad TV, inspired by the far-more-than-a-comic-book Mad Magazine, and we mustn’t forget Songs of the Pogo, a three-person revue of Walt Kelly’s work, seen only in Chicago in 1992.

The appeal of comics as a source for theater probably is obvious, beginning with the large potential audiences among the readers of various strips or books. Next, the fantasy aspects of some comics—Little Nemo and Spiderman are prime examples—lend themselves to visual spectacle. Finally, the literary quality of comics tends towards the exaggeration of characters and situations, especially among those comics featuring super heroes and arch-villains, and the simplification and repetition of storylines.

Even so, the process of comic page-to-stage transformation isn’t a sure thing, as the fate of It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane, It’s Superman proves (it was a failure). Whether in book form or strip form, comics are like soap operas: they come with oodles and oodles of backstory, they have villains who never are dead no matter how many times they’re killed off, and the heroes never quite woo and win the love interest. Intertwined storylines go on and on and on. Theater must solve the problem of creating a story with a finite beginning, middle and end, and with sufficient exposition to make characters and situations clear.

Then, there’s the matter of tone: get it wrong and you’re doomed, which is precisely what happened to It’s a Bird … Superman. The 1966 show survived only three months on Broadway because it decided to spoof the comic book and also invented a villain rather than using one from the Superman books themselves.

Comics may be easier to adapt to the stage if they are suitable for a revue format, as was the case with Peanuts, Pogo and Mad Magazine. The Addams Family—still touring but closed on Broadway after a 21-month run—might have fared better as a revue show vs. a book show. A number of the famous single-panel gag cartoons of James Thurber were incorporated into the very successful 1960’s show, A Thurber Carnival, although that still-performed revue also had Thurber’s short stories upon which to draw.

Turnabout is fair play and the career of Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa is a prominent example. He’s the author of Sensational Spider-Man, Marvel Knights 4 and Fantastic Four comics and also the author of a dozen plays, with Say You Love Satan, Dark Matter, Based on a Totally True Story and Good Boys and True among his works staged in Chicago at theaters from storefronts to Steppenwolf. Many of his plays, although not all of them, draw on horror/fantasy genres common to comic books. Ironically, Aguirre-Sacasa authored a revised book for It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane, It’s Superman at the Dallas Theatre Center in 2010.