Watching “Minari,” I Saw My Immigrant Experience On The Screen For The First Time

The struggles of growing up Korean American in Annandale, Virginia, came flooding back to me in Lee Isaac Chung’s new film.

By Esther Yoon-Ji Kang

Watching “Minari,” I Saw My Immigrant Experience On The Screen For The First Time

The struggles of growing up Korean American in Annandale, Virginia, came flooding back to me in Lee Isaac Chung’s new film.

By Esther Yoon-Ji KangWhen our family arrived in the United States in 1989, we quickly discovered the magic of yard sales and alley finds. At yard sales, we bought housewares for a quarter a piece, a 1970s couch for $40, an armful of toys and stuffed animals for a buck. In back alleys, we found free mismatched dining chairs and mid-century modern telephone tables — now very much back in vogue, I hear.

At the time, we were living in a roach-friendly apartment complex in Annandale, Virginia, a hub in the Washington, D.C. area for many lower-income immigrants during the 1990s. It was poorly-lit and cramped, but it was a place to make our own after a two-month stay at the home of a Korean woman who hosted new immigrants. One day, my father came home with a 10-by-15 piece of carpeting from an alley nearby. At that time, we thought it was a rug, but now I realize it was a scrap piece of leftover carpet — the kind a stingy landlord might install in a slipshod rental-unit renovation.

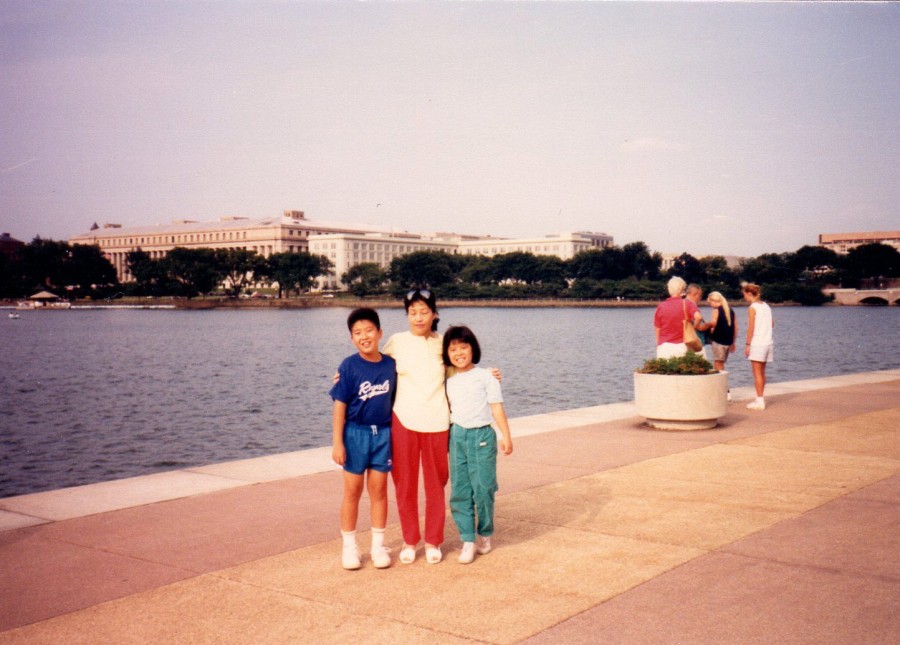

My dad wanted to wash his new alley find, but he didn’t know about carpet cleaning services — nor could he afford it. So our entire family — my parents, brother, grandmother and I — headed down to a nearby creek with the rolled-up carpet. I cannot trace my father’s reasoning for washing the carpet in that creek; I imagine that very act probably contaminated the scrap even more. In any case, on that summer day in 1989, our family washed the carpet along the bank of the creek. I was 9 years old, and I still remember the feeling of the cool stream around my ankles.

This was a memory buried deep in my mind, likely suppressed by the same shame that kept me from inviting friends to our apartment or taking the food we ate at home to school for lunch: Poor is bad, different is bad — both notions so egregiously false I wish I could travel back in time to tell my child self that these are lies, to tell her to hold her head high.

The memory of my family by the creek — from our “hardcore years,” as my brother and I jokingly refer to them — bubbled to the surface as the closing scene of “Minari” faded to black and the credits rolled after a virtual screening I attended in November. The new film — based on the childhood memories of Korean American director Lee Isaac Chung and starring Korean American actor and Second City alum Steven Yeun (“The Walking Dead,” “Okja,” “Burning”) — has been garnering praise and generating awards buzz. It was even the subject of some controversy recently, when the Hollywood Foreign Press Association rejected the film from entering the Golden Globes’ Best Picture race because it was predominantly in Korean.

“Minari” has been described as a story about a Korean American immigrant family — a concept so specific and loaded for me that as soon as I hit “play” on the trailer a few months ago, I began to tear up. My instinct then was to “claim” the film right away: This one is about, and for, Korean-American immigrants and their children. This one is almost better than “Parasite.” That one was a South Korean film, and I was so proud when it swept awards season, but this one — this one is about my parents and my brother and my grandmother and me in the United States of America. This one is ours.

That’s what a lack of representation does: It makes you rabidly proud and irrationally possessive of something that finally reflects you.

Chung, the filmmaker, has said his intent was to make a film for everyone. During a Q&A after the virtual screening, he said, “We just didn’t want this film to be something that people compartmentalize as being, ‘this is an immigrant story about this director’s parents.’ It felt like it needed to go to that register of creating more of a human story that could work … on a universal level.”

The film does that, I think. But the way it conjured up memories of my own family’s early years in the U.S. — painful, hilarious, harrowing, bizarre ones — tells me there is a specific power, a particular magic, in seeing an authentic reflection of something approximating one’s own experience, especially for people of color. As entertained and moved as I have been by countless films and TV shows throughout my life, none in recent memory has evoked so much stuff, for lack of a better word, as this film has.

The way Yeun’s character, the patriarch, would raise his voice or sit alone, stewing in his white, sleeveless undershirt, reminded me of my own father and the fear he sometimes invoked in my brother and me. As children, we didn’t understand his perpetual anger and anxiety. Now I recognize them as byproducts of what I call “immigrant life stresses” — finding jobs only to lose them months later, not being able to understand the language of the world around him, scrambling to make rent each month, trying to maintain ties with relatives back in the motherland, daily losing his grip on the elusive American dream.

Of all the imagery in “Minari,” though, the most powerful, for me, was the way the character of Monica, the wife and mom played by South Korean actress Han Ye-ri, wiped her tears during her arguments with Yeun’s character. She always wiped them swiftly, with dignity, as if they were a waste of time. That’s how my mother cried when she argued with my father over, well, immigrant life stresses. In South Korea, she was a brilliant, spunky social worker who helped orphans. Here in the States, she worked in a Kmart stockroom, a dry cleaners, a shoe-repair shop and a convenience store. This year, she was forced into retirement at age 70. The law firm where she worked as a conference-room aide — setting up lunch and coffee for attorneys half her age, cleaning up after their meetings — laid her off when work-from-home became a semi-permanent policy during the pandemic.

In the “Minari” Q&A, Chung said he started off his career “thinking that I wanted to make films that aren’t about my life.” But after making this film, he acknowledged that “it felt precious … to have something that I can show to my family both to my parents, in which they feel like they were seen and heard, and then also to my daughter, something I can leave behind to her, that she can see where we come from.”

Beyond being a gift to Chung’s loved ones, “Minari,” for me, is a reminder that we need more, not fewer, stories like this today — more movies, more books, more poems. To help us understand one another beyond stereotypes and caricatures, to find common ground, to make many feel seen for the first time and embolden them to tell their stories.

Seeing one’s own life, culture, and perhaps more importantly, their economic class, mirrored in a film is not a common experience for many immigrants — and more broadly, for people of color. Recently, Hollywood has held up films like “Crazy Rich Asians” and “Always Be My Maybe” as examples of Asian-American representation. But they still portray a life that does not reflect mine beyond the color of our skin. “Minari,” which features a leaky mobile home and a cursed farm for much of its running time, is a truer reflection of the precarious struggle of my family and many others like us.

All my life, I’ve watched characters like Kevin McAllister in “Home Alone,” Kelly Kapowski on “Saved By the Bell” (the original series, not the 2020 remix), the well-coiffed 20-somethings on “Friends.” They were entertaining enough, but difficult to relate to. Frankly, meaningful representation wasn’t something I even knew to expect. But more than three decades since that summer day by the creek, I am thrilled to finally see a film that represents my family and me. It joins a growing canon of thoughtful films about the immigrant experience.

It allows me to say: This one is about us. This one is ours.

Esther Yoon-Ji Kang is a reporter for WBEZ’s Race, Class and Communities desk and WBEZ’s Education desk. Follow her on Twitter @estheryjkang.