What’s behind the taste and smell of Chicago’s tap water

By Jennifer Brandel

What’s behind the taste and smell of Chicago’s tap water

By Jennifer BrandelJaemey Bush grew up in northwest suburban Glenview and now lives in Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood. Is she some kind of tap water enthusiast or something? No, but she’s definitely a tap water drinker and she passed us a glass and a question:

Why does Chicago tap water have a distinct smell? Suburbs don’t have it.

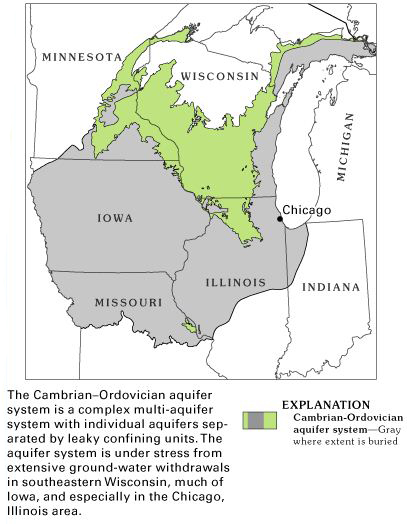

But the water that gushes out of many local taps is sourced from below ground. The northwest suburbs, for example, draw from the Cambrian-Ordovician Aquifer, which, like other aquifers, holds water in permeable rock formations.

Sourcing is not necessarily an “either/or” scenario, however; some southwestern and western suburbs (as well as cities such as Aurora) blend water from rivers (surface water) and aquifers (groundwater).

“Surface waters usually have lower mineral content than ground water,” she says, “because groundwater is touching all those rocks under the earth. They naturally have more minerals.”

Dietrich explains there’s no agreement about what makes water source tastier than another, but “In general, studies have shown that Americans like medium- to low-mineral waters. The Europeans really like high mineral waters.”

• Microbial contaminants such as viruses and bacteria, which may come from sewage treatment plants, septic systems, agricultural livestock operations and wildlife.

• Inorganic contaminants such as salts and metals, which can result from urban stormwater runoff, industrial or domestic wastewater discharges, oil and gas production, mining or farming.

• Pesticides and herbicides including synthetic and volatile organic chemicals, which are byproducts of industrial processes and petroleum production. Gas stations, urban storm water runoff and septic systems can contribute these, too.

• Radioactive contaminants, which may be naturally occurring or be the result of oil and gas production and mining activities.

These bullet points are from Lake Zurich’s 2012 Water Report. Similar language is found in water reports from every municipality, thanks to federal and state laws.

Most of these contaminants can affect taste, but you may ask: “Don’t we treat water?” If it’s from a municipal supply, yes. But treatments differ and all the filtering and chemical tinkering changes taste, too.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) sets what’s considered safe and legal when it comes to levels of contaminants. That doesn’t mean there’s no salt or metal swimming around in your drinking glass, for example; the EPA limits how prevalent they can be. In other words, the agency doesn’t say what’s clean so much as it declares what’s clean enough. That means there’s always a little stuff left behind from treatment, and that’s got potential to make water taste either fantastic or funky.

But she says another aspect of the Lake’s water is that it “has taste- and odor-causing compounds caused by seasonal algae growth.” Putz says the algae can make the water taste or smell fishy, and that this flavor is most common in the spring and fall during algal blooms and die-offs.

To neutralize that fishy scent, she says they use activated carbon, which is akin to charcoal used to clean fish tanks. Putz says another taste factor is the fact that “We keep our water fresh. It doesn’t sit in your pipe very long. We pump on demand and we pump exactly how much we need to pump out to consumers. We don’t have water towers in Chicago.”

To help avoid exposure to harmful metals, Mueller says, the AWWA and the USEPA recommend flushing your faucet for a minute whenever you haven’t used it in more than six hours. They also recommend that you drink and cook with cold water.

The taste of “very American” water

For Jaemy’s sake I promised not to get into the subjective element too quickly, but now the time’s come to meld the science of water quality with our experience of the stuff. She stated a strong preference for water from her hometown, Glenview. She’s picked up on a distinction and — paired with a preference — that’s an opportunity for competition, an impulse that’s played out in the water utility industry for years.

Dietrich has taken part competitive tap water tastings and can describe their methodology. She says the water should be served in glass (as plastic and other materials can affect the water’s taste) and at room temperature. Judges, she says, should agree on a rating scale and lay out what language they’ll use to describe what they’re tasting. Lastly, it’s ideal, she says, to cleanse the palate in between tastings. Unsalted crackers are up to the job.

If this seems as fun to you as it was for us, download this handy water tasting guide that our intern Logan made (based on this tasting guide from Terrific Science) and hydrate ‘til you’re silly.

The taste habit

Despite the many factors outlined above that can contribute to the odor and flavor of tap water, there’s another crucial variable that can change everything: you. Not only do the enzymes in your mouth, the strength of your sense of smell, and the sensitivity of your tongue play a role in how water tastes to you, but so does your brain.

Deirdre Mueller of the AWWA says “It’s very subjective. Most of us tend to prefer the water we were raised on. If you grew up on Chicago water, that’s the water you’re used to. That’s the water that you like to drink.”

If that is indeed the case, then one answer to Jaemey’s question may simply be: Chicago’s water smells and tastes funny because you grew up with Glenview’s water … and all the stuff in that water made quite an impression.

Alexander Jerri conducted many of the interviews used for this report.