Why Don’t Black Chicago Neighborhoods Gentrify?

By Natalie Moore

Why Don’t Black Chicago Neighborhoods Gentrify?

By Natalie MooreOn 64th and Ingleside in the Woodlawn neighborhood, Romarez Moody’s converting a two-flat greystone into a single-family dwelling. The touches are fancy: heated floors, fake chandeliers for closet lights.

And lots of space.

“You can ride a bike and it gives you the Huxtable feel of a home,” Moody said while showing off the second floor hallway.

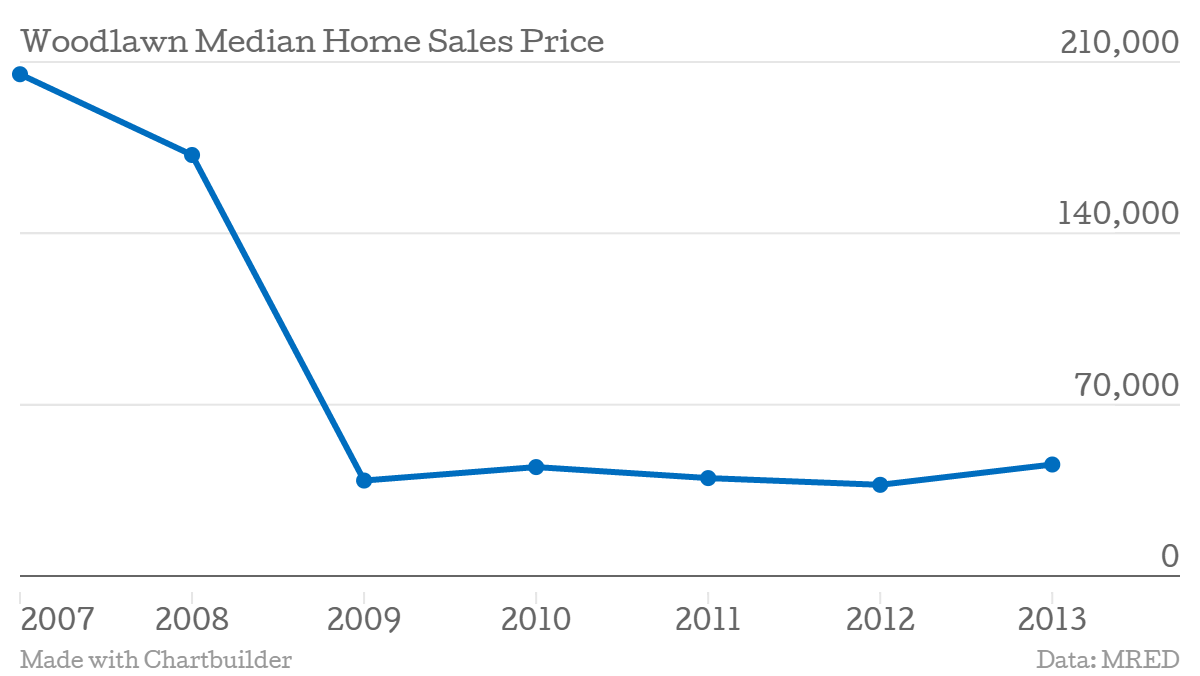

Moody’s selling these homes for $500,000. That’s pretty steep considering Woodlawn’s median home sales price was just $46,000 last year. The investor is taking advantage of the recession aftermath.

“There were several short sales, which brought new buyers into those properties at an affordable price. That drove down the market and made it more affordable for developers to come in and do what we’re doing here,” Moody said.

Before the housing crash, Woodlawn was on an upswing with condo conversions. Back then the median home sales price was $200,000.

Other nearby black communities were also revitalizing — neighborhoods like Bronzeville, Woodlawn, Washington Park and Oakland. Some worried that gentrification was underway.

“Instead of it being white people in Bronzeville it’s black people of middle class and upper middle class basically taking advantage of good housing prices,” said Janet Smith, a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago who studies neighborhood change.

“It raises this question, is there black gentrification?”

According to Smith’s research the answer is “no.” Several black Chicago neighborhoods experienced change over the last decade or so. Improvements were made in these South Side enclaves. Then the economy crashed. One reason these areas improved — but didn’t gentrify — is that they started out so far behind.

Smith and her team at UIC used census data to create the Gentrification Index.

She says while wealthier black newcomers moved into greystones, boosting home prices and median incomes, that only went so far.

“What’s going to do the rest? What’s going to bring in the grocery stores? The boutiques? The kind of things that go along with the whole package,” Smith said.

People tend to think of gentrification as white people displacing people of color. But race is just one of the factors in UIC’s index. At its core, gentrification is about class so in theory, black gentrification is possible — except it never quite happens in Chicago.

“If there isn’t sort of an infusion of a lot of capital to support that, or if in the case of black consumerism what we find is retailers still have an aversion to black consumers. Even if they have the green, they’re still black,” Smith said.

Recently, Harvard University researchers found that in Chicago, gentrification seemed to grind to a halt in places where the population was 40 percent black.

And yet looks can be deceiving.

People may drive by elegant homes, notice all the public housing that’s been demolished and wonder, how is this not gentrification?

Smith is referring to empty land once occupied by public housing. Much of the mixed-income replacement housing hasn’t been built.

But in other cases, it has.

Oakwood Shores replaced the Ida B. Wells public housing low rises.

Mary Smith used to live in Ida B. Wells.

“It’s much better because it was so much drugs over there then. It’s a little drugs but not like when the projects were here. Every morning you come to go to work, they were still out. Never go to sleep. Never go to sleep,” Smith recalled.

Now she lives on a subsidized housing voucher in nearby Washington Park, but is still connected to the area and appreciates the new amenities.

“I love over here. But I ain’t far away. That’s why I come back. This is where I originated from. So I ain’t never just gonna forget it. They got the track over there. We didn’t have that at first. I’m glad they put one. I can walk now. Lose some weight,” Smith added laughing.

Smith and her friends frequently hang out at Mandrake Park on 39th. The park has lots of recreational facilities, a playground and even tennis courts. Back in the late ‘90s former Alderman Dorothy Tillman worried those courts would attract white people and lead to gentrification.

Turns out the area is still mostly black, and again, never experienced gentrification.

“The labels gentrification, upgrades, that’s not really my concern,” said attorney Stephen Mitchell, a Bronzeville resident and co-owner of Gallery Guichard. “When I moved here in ‘99 over the years after that, the property values were skyrocketing. Every black professional that I knew, they were all clamoring to get into Bronzeville. The prices had went up. You had all this equity in your house.”

But momentum fizzled after the market crashed, leaving buppies hundreds of thousands of dollars under water.

Now life in the neighborhood is slowly coming back.

You can hear it on a recent Friday night at Gallery Guichard, with its big picture windows that look out over 47th street. An art competition is the cause for celebration. Art from the Black diaspora hangs on the walls. Martinis flow. House music pulses.

“We’re sort of on an upward trajectory because people do see the businesses coming up here at the gallery we opened. The Walmart is here on 47th on Cottage. People know about the Mariano’s that’s coming on 39th and King,” Mitchell said.

In a way it’s a return to Bronzeville’s past, when 47th Street bustled with activity. Of course that same past includes a legacy of segregation that restricted housing and limited blacks’ economic opportunities.

This complicated history resonates with activist Harold Lucas. As Bronzeville rebounds, he’s on a mission to make it a tourism heritage district.

“I think it’s going to be an upscale community. You will see upscale venues. I think you’re going to see a lot of small plate stuff just like you see on the North Side. I think you’re going to see that same element coming out of the spirit of African Americans with a very deep understanding of what my sweet potato pie should taste like,” Lucas said.

That means a neighborhood where black entrepreneurship is thriving and the cycle of poverty is broken.

Even if it’s not technically gentrification.

Natalie Moore is WBEZ’s South Side Bureau reporter. nmoore@wbez.org Follow Natalie on Google+, Twitter