With new garbage grid, Mayor Emanuel trashes symbol of Machine power

By Elliott Ramos

With new garbage grid, Mayor Emanuel trashes symbol of Machine power

By Elliott RamosOld grid New Grid

Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel killed the last of the Democratic Machine last week.

Well, not quite.

The finalization of Chicago’s new Grid Garbage Transition marked a dramatic change to the city’s refuse collection grid. Its workings were left largely unchanged in the past 100 years.

That system has strong and storied ties to Chicago’s Democratic Machine, which used city services as political levers to curry favor with voters — and as a vehicle to dole out patronage jobs.

“Adopting the grid garbage collection system allows us to replace an outdated method that started when garbage was still collected by horse and buggy and divert personnel resources to support the citywide expansion of recycling,” Emanuel said in a statement last week.

Chicago’s garbage collection was based on the boundaries of the city’s 50 wards, the recent re-map of which was the subject of controversy and a federal lawsuit.

While ward boundaries zig-zag across much of the city’s geography, the daily garbage routes put even the most gerrymandered territories to shame, resulting in a kaleidoscope of pickups, rarely viewed by the public.

It’s those convoluted routes that Emanuel says costs the taxpayers $18 million in labor and fuel.

According to the mayor’s office, by moving to a grid garbage collection system, “the Chicago Department of Streets and Sanitation will reduce its average daily refuse collection truck deployment from nearly 360 trucks to less than 320 trucks each day, while using fewer crews and fuel.”

Garbage collectors and garbage truck drivers have largely been union workers, but the status quo of sanitation services has evolved throughout the years, especially in Chicago.

“In the old days, when I was alderman, we still had 50-gallon drums,” said Dick Simpson, a former alderman and current University of Illinois-Chicago professor.

Simpson served as alderman for the 44th ward from 1971-1979. He said the office would get complaints if garbage wasn’t picked up or if there were special pickup needs such as mattresses.

And he said good garbage collection was good politics.

“Mostly it was used to make the voters happy and to get the voters to vote for you,” he said.

Simpson said addressing other city services such as tree-trimming, fixing curbs and street repair often went a long way with voters too.

When Chicago’s Democratic Machine was at its zenith, party bosses, committeemen and precinct captains utilized the ward-controlled distribution of city services to give priority to those loyal to the party. And since many services were under the control of an alderman, it cleared the way for patronage jobs.

Simpson said the patronage system still hasn’t died out, but it’s been cut back.

“Under the Shakman cases, there were 20,000 patronage workers,” he said.

“Under the Sorich trial, the clout list of people seeking patronage appointments under Richard M. Daley were 5,000,” Simpson said, referring to the conviction of Robert A. Sorich, a former patronage chief of Daley’s.

That trial was sparked by an infamous Sun-Times investigation into Chicago’s hired truck program. It was found to have mob ties and employ deadbeat contract workers.

“Is everyone on a garbage truck a patronage worker? Not necessarily, but quite a few were and quite a few are,” Simpson said.

Simpson said that at one time, there was one driver and three loaders for each garbage truck. One was supposed to be sweep the alleys. With supervisors involved, there could be as many as five people for each garbage truck.

But as truck designs and garbage cans changed, so did the need for manpower.

The transition to the standard rubberized plastic bins began in the early ‘80s. Modern garbage trucks can clasp onto the 96-gallon bins for automatic loading. It allowed for one laborer to be dropped from each truck crew.

Before the plastic bins, larger crews were needed because of the hodge podge of receptacles used by residents was inconsistent — and messy. And before that, well, as Emanuel said: it was collected by horse and buggy. And that was only for residents in nice neighborhoods. Many Chicagoans did not even have the luxury of garbage cans and relied on dumps scattered across the city.

The creation of Chicago’s garbage grid did not fully take shape until the turn of the 20th century. Around that time, cities across the U.S. were dealing with increasing household and industrial waste, sometimes including coal ash and dead animals.

A report made to City Council in 1905 by the commissioner of public works sought to address serious issues with garbage at the time.

The commissioner was none other than Joseph M. Patterson, a storied Chicagoan, who went on to found the New York Daily News. He was also grandson to Chicago Tribune founder Joseph Medill.

Patterson was blunt in his report:

“Those who have interested themselves in the problem of garbage disposal in Chicago are agreed on this proposition: The dumps must go. Dumps poison the air for miles around; and if ground made by dumping is dug up years afterwards it is found still putrid. Dumping is a barbarous anachronism for a twentieth century city.”

Patterson documented how New York, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh dealt with municipal trash. He recommended the council adopt the method of “reduction,” which involved pressing liquid out of solid trash to make it better suited for burning or dumping.

While a 2011 Wall Street Journal article points out that Chicago currently uses three workers per garbage truck, the 1905 report called for a garbage teams of up to five workers per wagon. Each used about four horses. The report, with entries by the Assistant Superintendent of Streets, indicated that a typical team averaged two loads per day, with a ward employing between 8 and 19 garbage teams.

By 1914, a similar report indicated that burning trash was more commonplace and newer methods of transportation such as street cars were used to transport ashes. By this time, waste management began adopting barges and transfer stations to move garbage to a centralized location away from densely populated areas.

But even as new technology and transportation options took root, management was still handled by ward offices.

As the city’s population grew in the early half of the 20th century, so too did its political apparatus, with European ethnic groups settling into defined enclaves.

Ethnic identity was a major part of Machine politics, which sometimes capitalized on poor English skills of immigrants to function as a middleman between communities and the government. Those service jobs were often taken care of by precinct captains.

In Chicago, each ward elects a party committeeman, who would recruit precinct captains charged with getting out the vote.

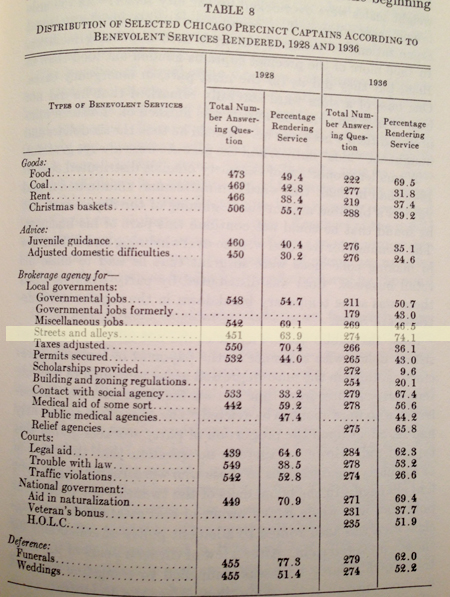

A survey, published in the 1937 study by Harold Gosnell titled Machine Politics: Chicago Model outlined services rendered by captains from 1928-1936. Among the services rendered were brokerage for streets and alleys, as well as providing legal aid, help with weddings, providing coal and handing out Christmas baskets.

These were generally used as trash receptacles, and up until the ‘70s were in use by many residents to burn garbage and leaves.

As the concrete receptacles fell out of use, residents switched to steel garbage cans.

Tim Samuelson is a cultural historian for Chicago’s Department of Cultural Affairs.

“Years ago in many neighborhoods, you requested a new garbage can from the alderman or the neighborhood Streets and Sanitation office. It was typically a recycled oil drum - sometimes repainted and stenciled with the politician’s name on it,” he said.

Then a shift to the plastic carts began in the 1980s, under the watch of Mayor Harold Washington. He began to more aggressively roll out and replace the city’s steel cans in 1985, according to a report by the city’s Department of Planning issued that year.

“When there was the change to uniform plastic carts, many local politicians were unhappy that this ages-old tradition of providing a garbage can to constituents was over,” Samuelson said.

That however, still did not stop some politicians from playing favorites, with some homeowners managing to secure multiple bins for for their homes throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Now, all that seems to have changed, with even aldermen acknowledging that it makes more sense for garbage to be handled by the city.

“As a former Chicago Department of Streets and Sanitation ward superintendent, I have first-hand knowledge of the city’s refuse operations and of some of the unique challenges each community can present,” said Ald. Michelle Harris (8th). “I’m pleased the department has developed a thoughtful system that meet the needs of residents while making smarter use of our resources.”

The sentiment was echoed by fellow Alderman Anthony Beale of the 9th ward.

“The ward-based refuse collection system is outdated and inefficient,” Beale said. “By transitioning to the grid system we can eliminate waste and redirect those valuable resources to support other service areas.”

While it remains to be seen how much the city will save off the new grid, much of the city’s attention has been focused on Chicago’s long-delayed recycling program, which floundered under Daley’s administration with the now defunct blue-bag system.

But one thing’s for sure: ward-based garbage in Chicago has been trashed.

Elliott Ramos is a data reporter and web producer for WBEZ. Follow him at @ChicagoEl

Documents

1905 Report to the City Council on Garbage Collection and Disposal by Chicago Public Media

1914 Report of the City Waste Commission of the City of Chicago by Chicago Public Media