Why some Chicago streets got numbers, others were stuck with names

By Carrie Shepherd

Why some Chicago streets got numbers, others were stuck with names

By Carrie Shepherd

As you may recall, Mark Sheldon of Evanston first posed this question to the Curious City gang, and I took on the investigation in late May.

He asked: Why does the North Side of Chicago have names for streets and the South Side have numbers?

Admittedly, I thought an answer would be easily accessible; maybe it would take a couple of calls to some local historians and maybe a tad more reporting beyond that. After all, I had a “go-to” crew of Chicago historians in mind, among them: Ann Durkin Keating, a leading force behind the Encyclopedia of Chicago, and Tim Samuelson, Chicago Cultural Historian. They offered various theories, ranging from the idea that the South Side’s use of numbers instead of names stems from the fact that it makes commutes easier, to the idea that it’s simply easier to number streets than to come up with novel names. The historians all agreed they had learned/read/heard the answer at some point, but they couldn’t quite recall the exact answer.

I was at a standstill. Frustrated, I thought: “I’m really going to let Mark down.” My editors Shawn Allee and Jennifer Brandel — the brains behind the series — reassured me that not every Curious City question has an answer, and it’s OK to reveal what I know without being a complete failure.

But I wasn’t totally convinced and, apparently, that kind of thinking didn’t convince Dennis McClendon, either. He’s a history buff who frequently leaves comments on the project’s website. I called him up and he explained that he happens to be a cartographer and loves nothing more than digging deep into the history of Chicago’s framework.

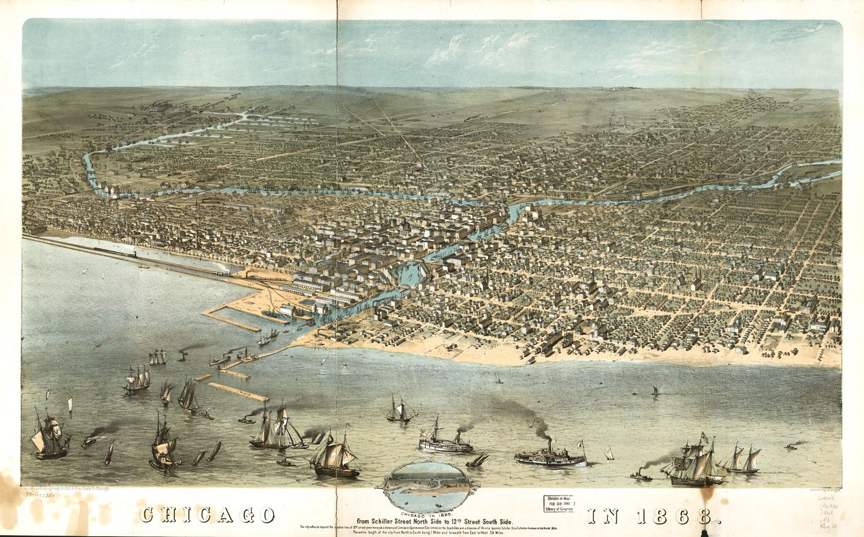

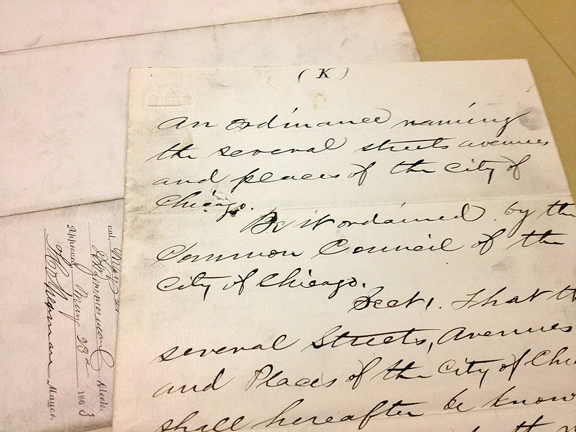

As I explained in an earlier story, McClendon has long been fascinated by this question about street names vs. street numbers, and he’d already combed some digital archives for an answer. He learned from an online search that an ordinance proposed in 1861 requested the switch from names to numbers in the South Division (South Side). This was a helpful lead, but the digital archives don’t tell the whole story; while they can provide the name and date of the ordinance, you have to take a trip to the basement of Northeastern Illinois University’s library to get the actual meat of these public records.

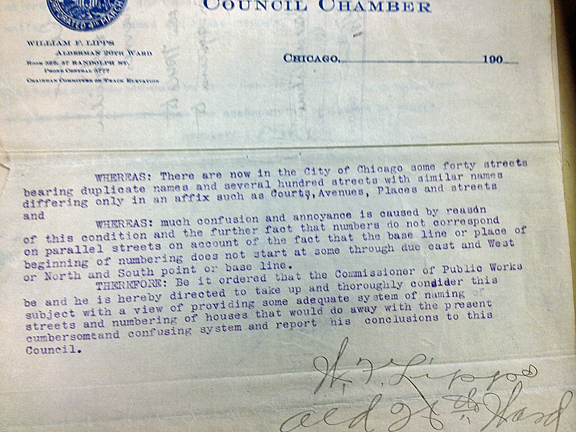

The problem we faced was that, while relevant ordinances contain terms such as “plan for naming streets,” we couldn’t find exactly what I needed; there was a lot of information about the use of North, South, East and West in street names, but nothing about actually referring to streets by number. The depository also has a lot of information about how Chicagoans got in the habit of numbering streets in the first place. One ordinance that talks about making street signs more visible contains a relevant passage. Here it is, couched in 1869-speak:

“To a stranger visiting, or even to the Denizen, in his walks throughout his Native City, one of the primary requisites to the facilitating his business or his pleasure-is to have the streets or public places named clearly and conspicuously everywhere to his vein.”

Still, I couldn’t tell exactly why — or when — officials started the switch to numbers on South Side streets.

I left the depository basement feeling a little defeated, despite having spent hours scouring the place and forming new bonds with the archive librarians. But as I returned to organize the chronology of what I had discovered, I realized something: I’d forgotten to look at the 1861 ordinance that McClendon suggested!

So, there you have it! The point of numbering streets on Chicago’s South Side was to create an easy-to-follow logic for commuters and visitors. Just like our original historians predicted.

It may not be the sexiest answer, but it makes sense, right? And, there may be more to come: McClendon found an old Chicago Tribune article that had street names one month in 1863 but then numbers later in the year. It’s an interesting development that has us wondering whether there’s more to plumb.

Question asker Mark Sheldon said, “That raises the question of why they didn’t do that to the entire city, right?” Indeed! We are not finished with this one.