Bayard Rustin: The Civil Rights Movement’s invisible man

By Robin Amer

Bayard Rustin: The Civil Rights Movement’s invisible man

By Robin Amer

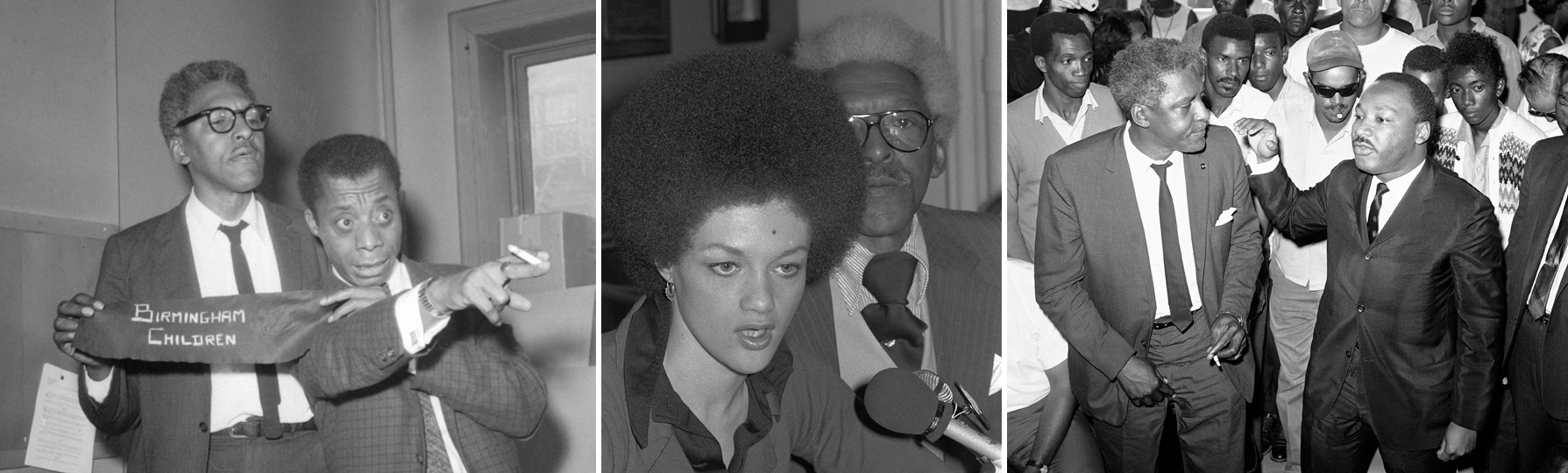

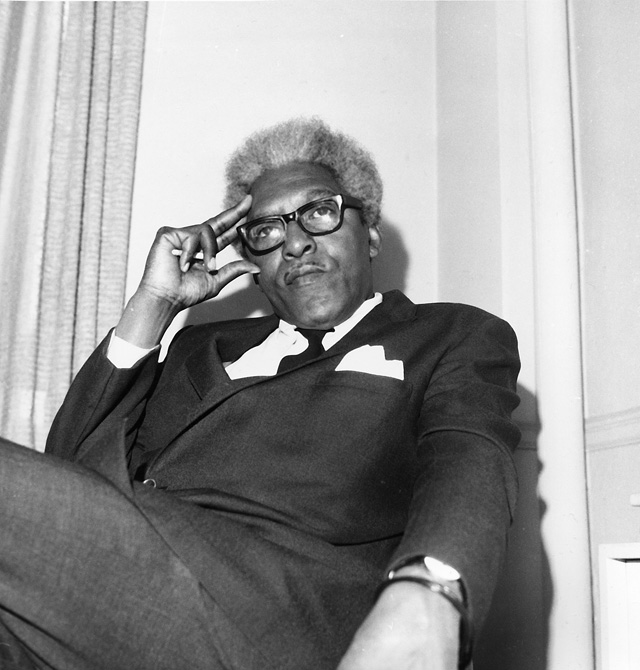

Look at the above pictures of some of America’s civil rights leaders, and you’ll see faces that are immediately recognizable. At their side, though, is a figure you might not recognize: bespectacled, focused and always in a tie. In one photograph he is Dr. King’s right-hand man and advisor. In another he stands behind Kathleen Cleaver as she defends her husband, Eldridge, former Minister of Information for the Black Panther Party. In the third image, he stands by the side of James Baldwin, one of the era’s most powerful thinkers. The man is Bayard Rustin. He’s little known today, but he had a profound influence on the Civil Rights Movement.

Rustin was by all accounts a dyed-in-the-wool radical: Raised by his Quaker grandmother, he was a devoted pacifist who traveled to India to study the non-violent teachings of Gandhi and brought those protest techniques to the movement. He helped launch the first wave of Freedom Rides.

At least a decade before Rosa Parks, Rustin refused to give up his seat at the front of a Tennessee bus. (According to a 1942 essay by Rustin, when police tried to drag him from his seat, he pointed to a white child across the aisle and said, “If I sit in the back of the bus, I am depriving that child of the knowledge that there is injustice here.“)

Additionally, Rustin was a longtime advisor to several movement leaders, including Dr. King and A. Philip Randolph, who organized and led Chicago’s Pullman Porters into the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first predominantly black labor union. Rustin was the lead organizer — and by some accounts the mastermind— behind the 1963 March on Washington, during which King made his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

So why did Rustin, a man who by all accounts was one of the most gifted organizers and public intellectuals of his time, not rise to the same level of prominence and regard as the powerful and influential people he advised? Why was he, as one commenter put it, “expunged” from the pages of history?

The wrinkle in Rustin’s story, and one reason you may not have heard of him, was that Rustin was also openly gay. He came out to his family in West Chester, Penn., as early as 1929, decades before it was remotely safe or acceptable to be a gay man in America.

Rustin’s honesty about his sexual orientation was thus at times a liability to him, even as it was a testament to his remarkable openness. He was arrested in Pasadena in 1953 on a morals charge – committing a sexual act in a public place, in this case, a parked car. He was sentenced to 60 days in prison and the case made headlines around the country.

According to filmmaker Bennett Singer, the director behind Brother Outsider, the 2003 documentary about Rustin, some people think Rustin was set up. Regardless, the incident was used against him many times, both by enemies of the Civil Rights Movement –North Carolina Congressman and segregationist Strom Thurmond attacked him from the floor of the U.S. Senate—and by his own brothers in arms. According to writings of Rustin’s referenced in the film, powerful U.S. Rep. Adam Clayton Powell, the first black man from New York to serve in Congress, allegedly threatened to spread a rumor that Rustin was having an affair with King if the two men didn’t call off protests planned for the 1960 Democratic National Convention in L.A.

Friends and family describe the delicate political calculus, both personal and public, that Rustin had to engage in with respect to his identity and his movement commitments. Sometimes he was able to step into the limelight; other times he was forced to take a step back.

In the audio above, two people close to Rustin discuss the impact this dance had on his legacy and his name recognition. The first is Eleanor Holmes Norton, congressional representative for Washington, D.C., as heard in Singer’s film. Holmes Norton met Rustin as a law student and then became his protégé. The second person is Walter Naegle, Rustin’s partner from 1977 until Rustin’s death in 1987. Both Holmes Norton and Naegle were close to Rustin, but they have very different takes on why he may have chosen to stay in the background.

Dynamic Range showcases hidden gems unearthed from Chicago Amplified’s vast archive of public events and appears on weekends. Bennett Singer and Walter Naegle spoke at an event presented by the Chicago History Museum in February. Click here to hear the event in its entirety.