Wire: Rock’s greatest super geniuses (after Eno)

By Jim DeRogatis

Wire: Rock’s greatest super geniuses (after Eno)

By Jim DeRogatis

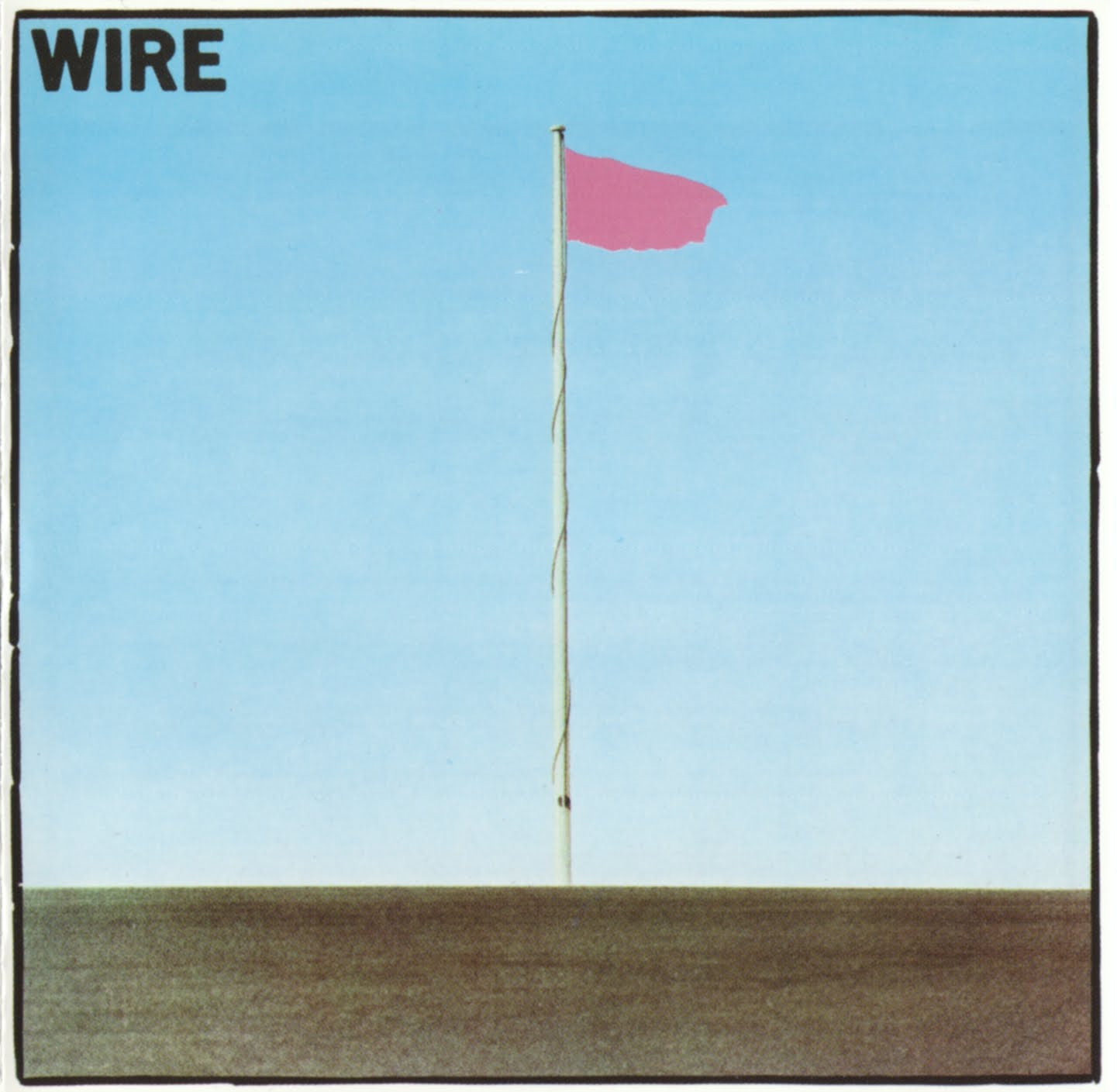

Asked to assess the most important part of the legacy of long-running English art-punks Wire, most fans will cite the quartet’s first three albums—Pink Flag (1977), Chairs Missing (1978), and 154 (1979)—which chart a startling arc of growth and creativity that echoes and inspires to this day.

If you value my opinion at all, and you do not own these recordings, you should download them immediately. Your life will be richer for it, and I’ll wait.

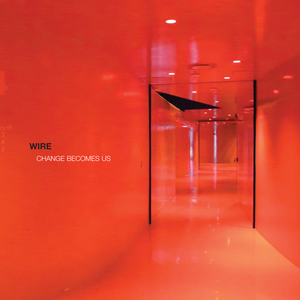

Done? Good. Because here I will venture that as extraordinary as that music is, a case can be made based on Read & Burn: A Book About Wire, an impressive 400-plus-page appreciation of the band by Wilson Neate newly published by Jawbone in the U.K. and distributed by Hal Leonard in the U.S., and Change Becomes Us, the group’s 13th studio album recently released on its own Pink Flag label, that Wire may prove to be best celebrated for its endless flood of Big Ideas, forever challenging the way rock bands interact, create, and evolve, to the point even of denying that the group has anything to do with rock at all.

In terms of philosophizing about the business of making an awesome noise, the only thinker who’s done more is that Great Theorist himself, Brian Eno.

Over the course of an on-again, off-again, ever-evolving 37-year career, Wire has introduced each new musical “object” (read: album or EP) with a grand theory: sonic, rhythmic, structural, technological, or all of the above and more. Some have been solid, undeniable, and timeless, some crackpot, misguided, and quickly dated, but all were declared in the moment with an unwavering dedication and sense of purpose. Eno had his Oblique Strategies; Wire has its Concrete Tactics. Of course, not every Big Idea has been a fruitful one, and as a guide for sorting through and trying to make sense of them all, veteran fans and new initiates alike can’t do better than Read & Burn.

Neate, an ex-pat Brit who earlier wrote in-depth about the group’s first album for the Wire’s Pink Flag installment of Compendium’s 33 1/3 series, tackles with equal passion, depth, and insight each distinct era of this complicated career: the initial burst that brought us those three classic albums, which was followed by a break of about six years; the “dugga dugga” days that began with the Snakedrill EP in 1986; a misguided period in the early ’90s when the artists were consumed by their own computers and foolishly marginalized drummer Robert Grey; and, after another break of about a decade, the ferocious incarnation that started early in the new millennium and which continues today, albeit with the loss of guitarist Bruce Gilbert.

Though the book is rich in varied perspectives from all of the key players, Read & Burn is less a conventional biography than one critic’s opinionated and insightful illumination of a daunting body of work by four extremely different and willfully perverse individuals. Neate’s theories about these arch-theorists take precedence over their own, which only is fair: This is his account, and the fact that every member of Wire not only has a different vision of Wire but often rewrites earlier versions makes concepts such as “definitive” and “objective” impossible, if they ever were desirable at all.

Here, the author slightly undersells the brilliance of Pink Flag, though he admits that’s largely because he’d already done the effusive gush in his earlier book, and he wanted to take a different approach this time (positioning the album more as a product of the punk explosion than as a radical reinvention of it). But in a brief Beat foreword, Mike Watt more than makes up for this, offering his own take on why this album has been so formative for bands ranging from the Minutemen, Mission of Burma, R.E.M., and Minor Threat to Blur, Guided by Voices, My Bloody Valentine, and Savages, to name but a very few.

To be sure, if Wire has given us one Big Idea on which a lesser band could base an entire career, it’s given us 100. Neate’s personal take on any one Wire album, era, or idea only encourages discerning readers to go back into the stacks, listen anew, and judge or reconsider for themselves; I can’t remember the last music book that sent me scurrying to play so many sounds again with fresh and eager ears. In the end, maybe you’ll think more highly of, say, The Ideal Copy than Neate or some of the band members do; perhaps you’ll hate Manscape even more. It’s all part of the fun.

Neate’s own Big Idea may be a bit more problematic. Basically, he argues that vocalist-guitarist Colin Newman’s rather dictatorial “pop” perfectionism always has ideally been balanced by Gilbert’s love of noise and embrace of chaos and confusion. (“Any form of disinformation is useful,” the sinisterly impish Gilbert once told me.) I more or less agree, and Gilbert’s “spanner in the works” is missed to some extent on the new album. But nothing ever is simple and clear-cut in Wire-Land, and Neate’s construction of the four-legged table somewhat shorts the contributions of bassist-vocalist Graham Lewis, the most lustful, poetic, and dare I say fun member of this posse of sometimes dour intellectuals, as well as adding to the near-universal under-appreciation of Grey, who not only is that rare drummer whose style and sound (minimalist though they may be) mark him as a singular voice, but who is genuinely a very nice man with a calming presence that cannot be underestimated in balancing the difficult forces of nature of the other three founding bandmates.

In any event, the fact that no member of Wire will be entirely approving of Neate’s reading of the charms and methodologies of Wire is one of the book’s strengths: This is just one exceedingly well-written and very passionate take on the band’s story and output, and too bad if the band doesn’t like it. As Lewis sang on 154: “I should have known better/Than to become a target/Albeit a target which moves.”

Ah, yes: the moving target. If all of this talk of ideas and theories seems joyless and pretentious, that neglects the fact that in consistently moving forward, Wire often disavows much of what it’s done in the recent or distant past. No one can take the piss out of Wire better than Wire itself. But the rush toward whatever is coming next always is so enthusiastic in concept and eager in execution that it’s impossible not to be swept up, loving the journey if not the destination. Plus, there usually are laughs aplenty along the way.

Personally, I’m vastly amused by Wire’s current rejection of one Big Idea from the Snakedrill/Ideal Copy days: the complete refusal to indulge in soul-killing nostalgia by playing any of its old material during its first extensive tour of the U.S. in 1987. (But then I would chuckle about that, given my own history with the band.) This doesn’t make that idea any less valid or brave: How many other artists ever have resisted giving the people what they want because they’re more excited about being here now or going somewhere new in the immediate future? Nor is it hypocritical; consistency, after all, is the hobgoblin of small minds. Finally, it certainly doesn’t invalidate the Big Idea behind Change Becomes Us, which attempts a different way to embrace the past in the present with an eye toward the future (or something like that).

When Wire first went on hiatus in 1980, it left behind a considerable body of work-in-progress, some of it heard in various forms of development on the sketchy 1981 live album Document and Eyewitnesses, as well as on scattered solo offerings and various obscure releases in the years that followed. The Big Idea on album number 13 is to return to these 32-year-old pieces and complete or reimagine them now, with Mssrs. Newman, Lewis, and Grey older if not necessarily wiser, and considerably younger guitarist Matt Simms assuming the role of Gilbert (sonically, if not philosophically; on board now for three albums, he has yet to assert himself on that front).

Think of someone picking up an unfinished Shakespeare manuscript and rewriting and completing it in the current vernacular, then doing a Burroughs cut-and-paste. That’s Change Becomes Us.

Now, as often is the case, something is just a little off in the realization of this idea. The original material is obscure even for Wire super fans, so the reimaginings are not necessarily as revealing or as much fun as they might have been. The only song that really grabs me in its juxtaposition of past/present/future is “Ally in Exile,” which opens the album in its new rendition and under its new title of “Doubles & Trebles.” What might have come of Wire 2013 reworking any one of the three masterpieces that started its career? I’d have been much more interested in hearing that, but then the lack of Gilbert might have been much more telling, whereas his twisted presence at least hovers in the background here, since he was in the thick of the original creation.

But with any new Wire offering, the idea only is one aspect of things. For all of the band members’ disdain for some of the words I’ve used—“fun” and “rock” chief among them—let us not forget that another purpose of the newest objet d’art is for us to listen to and enjoy it, however “American” that concept may be. (For this band, “American” and “rock” are pejoratives so nuanced with multiple levels of snarky meaning that no one who isn’t a perverse, nearly 60-years-old legendary English art-punk ever will fully comprehend them, while “fun” no doubt is a word that would leave even these loquacious chaps shuddering in speechless revulsion.)

Nevertheless, a fun rock album is what Changes Becomes Us is, and there ain’t nothing wrong with that. The connections to one possible abandoned future post-154 can be heard in a sonic palette that is more lush, moody, and ambient than that of more Spartan recent offerings such as Send (2003), where the snarl took primacy. Yet the new one also is more playfully inventive and subtly skewed though no less tuneful than Red Barked Tree (2010), a “poppier” effort by Wire standards. With or without Gilbert, the quartet still gleefully brings the noise, and the now properly honored human element and relentless drive of Grey is central; he always will be the soul of this particular machine.

The dreamscape of “Keep Exhaling,” the ambient and lilting “Re-Invent Your Second Wheel,” the highly caffeinated “Stealth of A Stork” (with Newman’s frantic yelps of “Change!” every time the chords shift), the gonzo anthem “Eels Sang” (“Eels Sang Lino” in its earlier incarnation), and the absolutely lovely “& Much Besides” rank with some of the strongest and most memorable songs Wire ever has given us—though “song” may be another of those words that makes this band sneer, so conventional is the very notion.

Is Change Becomes Us the musical or conceptual equal of the three albums Wire gave us at the start of its history? No. But the band seems at long last to have accepted that matching or bettering those peaks isn’t possible, while moving forward to climb new if more modest ones is a worthy and possibly even enjoyable endeavor. As a whole, the four albums Wire has given us since 2003, with the latest being the most ambitious and the logical summation, certainly are more consistent and rewarding than any since the first three. So it’s fitting that all of this looking back and summing up is happening now, on record and in print.

Which is not to say that Wire isn’t about to blow it all up again with the next Big Idea any second, god love ’em.

(Wire performs at the Pitchfork Music Festival in Union Park on Friday, July 19.)

Wire, Change Becomes Us (Pink Flag)

Rating on the four-star scale: 3.5 stars.

Follow me on Twitter @JimDeRogatis or join me on Facebook.