Minorities in Illinois politics: By the numbers

By Sam Hudzik

Minorities in Illinois politics: By the numbers

By Sam HudzikToday we continue our series Race: Out Loud with a look at how politics and politicians have changed over the last few decades.

Unlike many communities in the Chicago area, the halls of government are integrated. Still, politics is far from color blind, as racial and ethnic minorities fight to win - and hang on to - influence and power.

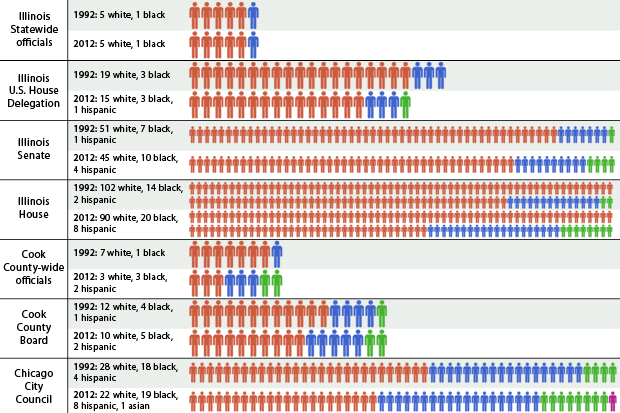

The numbers: June 1992 to June 2012

Latinos get a seat

Before 1983, there had never been a Latino in the Illinois legislature. Then there was a lawsuit, a federal court order and a candidate. By decree of the Democratic machine, a seat would go to Joe Berrios, a loyal precinct worker from Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood.

As Berrios tells the story, he got quite a welcome from his neighbor on the House floor.

“I sit down and I said, ‘Hello’ to him. You know, I’d never met the man before, but this was my seat,” Berrios recalled during a recent interview. “And his comment - now, this is after about an hour of sitting there - he goes, ‘Man, I can’t believe you speak English.‘”

“And I looked at him and said, ‘What? What are you talking about?’ And he goes, ‘Well, I’ve been here a few years and you know I figured the first Hispanic come down here would come in here with a big sombrero. We’d have to get a translator.’ And I looked at him and I go, ‘Excuse me?‘”

Berrios is now Cook County’s assessor - the first Latino to hold that job. He was also the first Latino on the Cook County Board of Review and the first Latino chair of the Cook County Democratic Party.

The first Latino in the Illinois Senate, Chicago Democrat Miguel del Valle, was greeted by similar ignorance when he arrived in Springfield in 1987.

Del Valle recalled that other senators were surprised his computer or typewriter could print in Spanish. They also asked him if Mexicans were considered Latinos and posed questions about Latino cultures and food.

Beyond those insights, Del Valle shared with the other lawmakers his personal experience of arriving in Chicago at age four from Puerto Rico, unable to speak a lick of English. That story, he said, helped save bilingual education programs from a funding cut.

“That’s why, in a representative form of government, it’s so important to have this cross-section that’s reflective of the society you live in,” said Del Valle, who later served as Chicago’s first Latino City Clerk. He ran an unsuccessful campaign for mayor in 2011.

Today, there are a dozen Latinos in the state legislature. Behind these numbers: a rising Illinois Latino population, and federal law requiring legislative districts with Latino super-majorities that could - but don’t always - elect Latino lawmakers.

Still, the representation growth has not kept up with the population growth.

Here’s now it breaks down: Latinos make up nearly 16 percent of Illinois’ total population, though less than 7 percent of the General Assembly.

By comparison, blacks make up less than 15 percent of the population, and roughly that same share in the legislature.

‘Did nobody slap me in my face?’

State Rep. Mary Flowers of Chicago began serving in the Illinois House in 1985, so she is the longest currently serving state lawmaker who is black. And in all her time, the Democrat said, she’s never felt blatant racism in politics.

“Did nobody slap me in my face? No. Did nobody try to tell me where I couldn’t park, where I couldn’t walk, where I couldn’t eat, the things that I couldn’t say? No,” Flowers said. “But then the laws and the legislation that has been passed in the last twenty years has been to the detriment - as far as I’m concerned - of a society of people.”

Flowers said that detrimental legislation relates to education and to crime that, perhaps unintentionally, she said, hurts Illinois’ black residents more than the rest.

Two decades ago, there were 21 black state lawmakers. There are 30 today.

Despite the increase, Flowers said black influence in state government has fallen in that time. She said members of the black caucus are less and less on the same page, in part because many represent more diverse districts, with a mix of residents who are white, black and Latino, city and suburban.

“People have to represent their districts. So therefore what’s happening in two or three communities in the city, that’s my priority. That’s not my colleague’s priority,” she said.

“Obviously politics has come a long way,” he said.

Davis said recent years have shown that black politicians don’t need majority black constituencies to get elected.

“A good example is Carol Moseley Braun, who got elected [in 1992] United States senator and did not have anything approximating a majority black electorate,” Davis said.

Same goes for a host of victories by black politicians in Cook County-wide elections, and then, of course, Barack Obama’s 2004 U.S. Senate and 2008 presidential wins.

A Republican color deficit

Davis is one of three black members of the U.S. House from Illinois, a number that hasn’t changed in more than 30 years, even as the size of the state’s delegation has shrunk. Illinois’ black members of Congress have all been Democrats, except for the very first one, Oscar De Priest, a Republican who served in the House from 1929 to 1935.

The last time there was a black Republican in the state legislature was 1983. State Rep. Jesse Jackson (of no relation to the civil rights family) opted to run as a Democrat when seeking a second term, and was defeated in the primary.

EXTRA: A Legislative Research Unit report on racial and ethnic minorities who’ve served in the General Assembly as Republicans (PDF)

As for Latino Republicans in the General Assembly, there’s only been one. Frank Aguilar, of Cicero, served from 2003 to 2005. There were none before him and there’ve been none since.

And that means when Republicans gather in Springfield, Aguilar said, “There’s no Latino Republican right now in the caucus to bring up Latino issues. There isn’t anybody so they’re not going to talk about it because no one’s bringing them up.”

That’s a problem, Aguilar said, for Republicans who need Latino political support, and also for Latinos.

“Someone says, ‘Well Frank. You’re the balance of the force.’ Well, you know, there’s got to be a voice in both parties. You know, it’s a two-party system,” said Aguilar, who now works as Cicero’s community affairs director.

Council map wars

With that, we turn to Chicago’s City Hall, where bipartisanship isn’t an issue these days; all the aldermen are Democrats.

In the last twenty years, black aldermen have seen their numbers basically hold steady, while the number of Latinos doubled, from 4 to 8, and will possibly grow under a new ward map approved this year.

No group got exactly what it wanted in that map - not blacks, Latinos, Asians or whites. The Polish certainly didn’t.

Once a forceful group in Chicago politics, the city’s Poles have seen their numbers in the council dwindle as Latinos and blacks gained seats. Now, as Mike Zalewski pointed out, he’s the only alderman with a Polish name.

“It’s not good that we have such a large Polish population and the number of Polish alderman has dramatically dropped off. But it’s up to people to get involved,” Zalewski said.

A fortune for color blindness

Zalewski has seen his ward grow more and more Latino. He said he represents them as fairly as he does his Polish residents, just as he said his colleagues of all stripes represent the Poles in their wards

And that brings up a key question: when will race and heritage no longer be a major factor when we’re talking about legislative maps and political representation?

“I want to see the day when it doesn’t matter who you are, what your ethnicity is, and you’re elected because of your capability and because of the fact that you’re responsive to constituents,” Del Valle said. “I want to see that day come.”

But, that day, Del Valle said, hasn’t come yet.