A century of waste: The evolution of Chicago’s garbage collection

By Simran Khosla

A century of waste: The evolution of Chicago’s garbage collection

By Simran Khosla

Working with dirty data can be messy, especially if it’s some of the old numbers found in yellowing-pages on library shelves.

Recently, we stumbled upon a treasure trove of statistics on early sanitation practices in Chicago.

In the early 1900s, the Department of Public Works published annual reports, complete with fold-out tables filled with data and hand-drawn maps of city service.

We compiled the information in the archives and combined it with current data from the city to give you a graphic look at how Chicago’s garbage collection system has evolved over the last century.

In 1905, the city’s garbage collection system was struggling so much that the Department of Public Works described it

“If there should be anyone who thinks otherwise (Chicago’s garbage collection is done well), he can be easily converted by watching from his alley the manner in which it is necessary to load his refuse on the city wagon; by following in the wake of a swill-soaked wooden wagon, particularly on a hot day; by observing the arrival of the wagon at the big clay pit dumps, surrounded by people living in some cases right at their edges; by witnessing the struggle of the horses in the mass of garbage, broken glass and tin cans in an effort to get their loads in position; by noting the laborious process of unloading with pick and fork, requiring from thirty to forty minutes; by experiencing the insufferable stench that must be endured by the people in the neighborhood; by realizing the immediate effect on their health and the danger for years to come from building over such a mass of corruption, in some cases 80 feet deep.”

A survey was conducted to see how garbage collection in the city was taking place. We transferred the hand-made tables into Web versions and created a map of the garbage collection system circa 1905.

|  |  | |||

| Click for full image | View as table | Click for full image | |||

The graph below shows how much garbage the city of Chicago was producing month by month in 1910 and in 2012.

Population estimates were detailed on the 1914 report, and 2012 population is based on estimates by the US Census Bureau.

In total, the city of Chicago produced 99,537 tons of garbage in 1910 and 892,034 tons in 2012. That’s about 97 pounds of garbage per person in 1910 compared to 657 pounds per person in 2013

But don’t be fooled, though it looks like we’ve increased the amount of garbage produced per a person nearly sevenfold, data work is rarely that simple. University of Illinois at Chicago Urban Planning and Policy Professor Ning Ai specializes in waste management. She explains, it’s difficult to draw a direct comparison between these numbers.

“Compared to a century ago, garbage not only differs in generation rate, but also in composition. Intuitively, the amount of garbage increases along with economic growth. For example, many packaging materials in the waste stream have changed from glass to much lighter-weight plastic and paper. Thus simply comparing the numbers either using the volume (e.g., by cubic yards) or weight (e.g., tonnage) may not reveal the challenges of waste management fully or even accurately.” Said Ai.

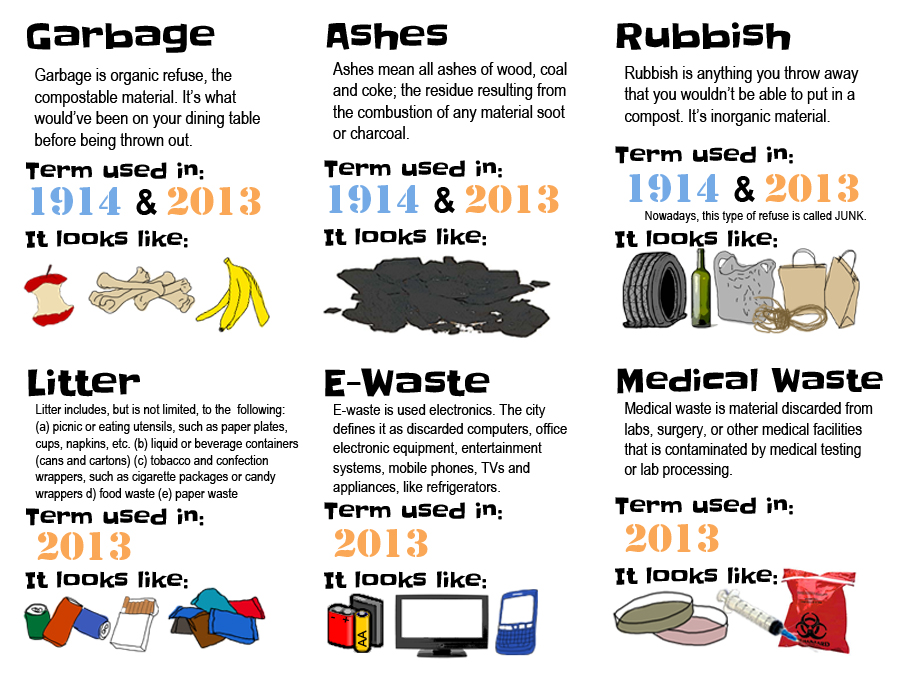

Today, we have entire categories of garbage that never existed in the 1900s. Check out some of the various categories of garbage that existed back then compared to the new stuff in today’s municipal code.

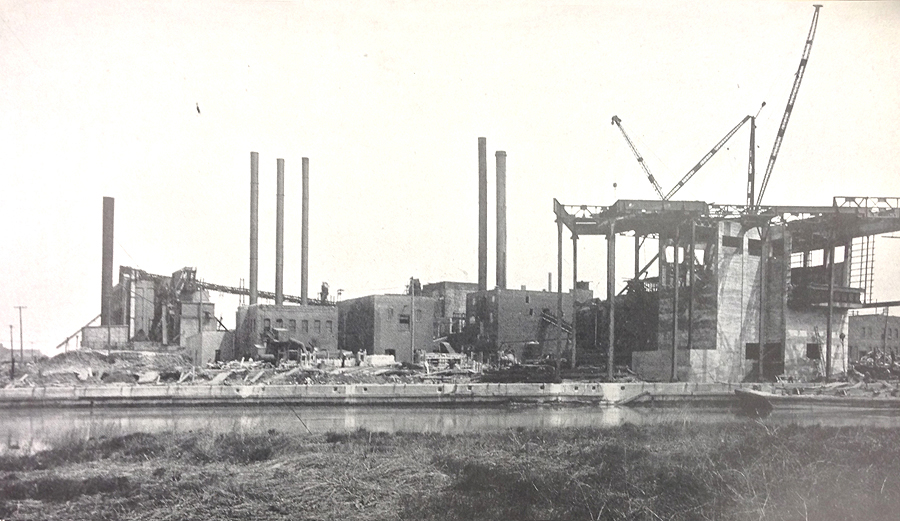

In the early 20th century, the organic refuse, also known as garbage, would be processed and reduced down so more garbage could be placed in landfills without taking up more space. Much of the inorganic matter would be incinerated because ash also took up less space in the fast filling city dumps.

Back then, landfills were the enemy, a 1905 Department of Public Works report said, “The dumps must go. Dumps poison the air for miles around and if ground made by dumping is dug up years afterwards, it is found still putrid.

Over a century later, landfills are still a massive problem for refuse collection in the city. The Chicago metro region has six active landfills, five of which are currently designed to reach full capacity within 10 years according to the Illinois Environmental Protection Act of 2011.

ldquo;Public opposition out of environmental and economic concerns have also made it increasingly difficult to build or expand waste disposal facilities in the city. The total costs of transporting the waste and dumping in a remote site are typically lower than disposing of within the city, and it is “out of sight, out of mind.” Said Ai.

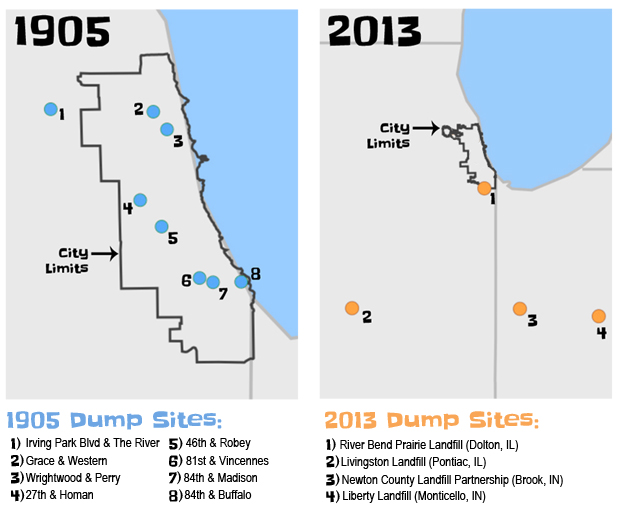

Most of today’s dumping sites are located well outside of the city limits. Below we compared Chicago’s dumping sites in 1905 to city dumping locations identified by Anne Sheahan of the Department of Streets and Sanitation.

Ai added that the cost of these preparations and the cost of transporting large quantities garbage to remote landfills also has a big environmental impact.

“The Chicago Department of Streets and Sanitation is currently working to roll out residential blue cart recycling citywide and is scheduled to be complete by the fall of 2013,” Sheahan said. “We will continue to work with residents through community outreach to encourage regular recycling across the city, which is not only good for the environment, but it can result in considerable cost savings for the city.”

Simran Khosla is a WBEZ intern. Follow her @simkhosla. Email her at skhosla@wbez.org.