Inmates housed in flooded basements, and Gov. Quinn keeping reporters out

By Rob Wildeboer

Inmates housed in flooded basements, and Gov. Quinn keeping reporters out

By Rob Wildeboer

Today we turn our attention to another prison that Quinn is keeping out of public view.

Vandalia is in southern Illinois, and some inmates there are housed in basements that regularly flood and are likely filled with mold. We’ve talked to several former inmates who say when they complained about the living situation they were threatened by prison employees. One of them is a man named Louis Wilkins.

Because of his drug and alcohol addictions, Wilkins has spent much of his adult life in and out of prisons. He did his most recent stint at Vandalia.He ended up there because he had been working construction for a friend and the friend refused to pay him for work he’d done.

There’s no need to go into all the details, but being ripped off was the final indignity in a long string so Wilkins decided to take action. He broke into his friend’s truck, stole some equipment, and as you’ve already figured out, he was caught.

Wilkins pleaded guilty and was sentenced to four years. At Vandalia, he was assigned to live with a hundred other men in a basement room. When he first got there other inmates warned him that after it rains the basement floods.

He figured that meant a few wet spots here and there.

Not so.

Wilkens says there was an inch of water across the entire room, and they’d use shop vacs to clean it up but the water kept coming.

“They put us actually on shifts at night, he said. “I’m laying here sleeping I got somebody next to me using the shop vac, you know, and this here for like two three four days at a time that we would have to do this here, constantly, around the clock.”

Wilkins says, in the bathroom, when you flushed the toilet, sewage would seep through cracks in the floor.

I talked to several Vandalia inmates who said it was so hot and humid in those packed basements that condensation would collect on the ceiling and drip down on them.

Recently released inmates, including Wilkins, said there was also a lot of mold and the prison’s fix was to simply paint over it.

But Wilkins says I don’t have to believe just him.

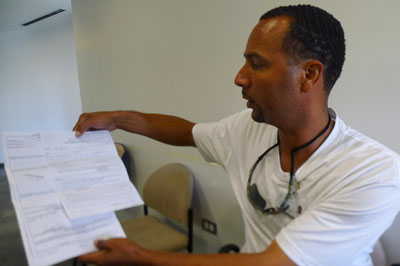

He picks up a print out of a report on Vandalia done by the John Howard Association, a non-partisan group that monitors prisons.

“Like my word ain’t too good because I’m a convicted felon but the word of these people who come down here, their word weighs a little bit more and it’s all in their report,” he said. “Thank God they made it there and they got in. I can actually show you.”

The 19-page report details the John Howard Association’s observations and then provides explanations given by prison administrators.

For example, John Howard saw a flooded basement.

The Vandalia administration said it was an anomaly.

John Howard noted bare wires hanging from the ceiling where there used to be a light fixture.

The administration responded that the incident hadn’t been reported.

John Howard volunteers breathed air in dorms that was dank and smelled strongly of mildew and mold.

The administration had a staff member assess the air and their report found that Vandalia is better “than most facilities at inhibiting mold growth.”

I’m no expert, but that doesn’t sound like the gold standard of mold suppression, and in their report John Howard researchers seemed skeptical too, noting that the findings were hard to reconcile with their observations.

We wanted to go see Vandalia for ourselves and report back to you on conditions that seem to warrant a closer look.

We’ve been seeking access for several months, but Gov. Pat Quinn is keeping us out.

According to Quinn spokeswoman Brooke Anderson, reporters can’t visit the minimum security prison because of safety and security concerns.

So, what exactly are the safety and security concerns?

That’s one of the questions we have for Quinn, but Anderson has refused to go on tape to answer our questions.

And now, I’ve talked to several former inmates like Louis Wilkins who say, when they tried to voice concerns, they were threatened with retaliation by prison employees.

“You know, I had to pipe down on the situation because I was trying to go to school to get my GED.”

Wilkins says when he asked for grievances, the forms inmates use to write out complaints, the correctional officers said he needn’t bother because they’d just throw out the grievances anyway.

And he says they also threatened to put him in segregation, which would have meant he couldn’t attend GED classes.

In a written statement, the Department of Corrections says the allegations of threats are disturbing, but it has found no merit to the claims, though the department says it’s a serious matter and will be reviewing the issue further.

As for Wilkins, he says he stopped complaining so he could get his GED but he’s simmering with anger for how he was treated.

“I committed a crime and the judge sentenced me,” he said. “He did not say, Mr. Wilkins, you will be sentenced to four years living in unhealthy conditions to be treated, or housed like an animal. I wouldn’t even house an animal like that.”

Alan Mills is an attorney with the Uptown People’s Law Center in Chicago, which is suing the Department of Corrections over conditions at Vienna, the prison we reported on yesterday.

“If you’re going to choose to lock up almost fifty thousand prisoners, then you have to pay the bill for doing it in a humane decent way. The constitution doesn’t say you have constitutional rights if you can afford them. The constitution says you have to do this, so Illinois either has to let some people out of prison or improve the conditions, which is going to mean spending more money,” he said.

Mills says they’ve got a lawsuit against Vandalia that they’re ready to move on, but there’s a problem.

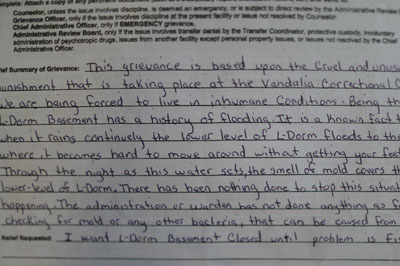

In order to file a lawsuit, inmates have to complete the grievance process at the prison—a lawsuit can’t be filed as long as a complaint is still pending.

Mills says he believes prison administrators are purposely sitting on those grievances to make a lawsuit impossible.

“I mean some grievances get dealt with within a week. After six months, I know from my personal experience that clearly somebody is slowing things down.”

In a written statement the Department of Corrections insists they strive to promptly respond to all grievances and appropriately address concerns raised in complaints.

As for the lawsuit Mills hopes to file, it’s focused solely on conditions, he said, “This is purely a forward looking lawsuit. We are not trying to figure out what living in these conditions is worth to somebody and therefore trying to get damages for all these individual prisoners. Nobody’s trying to get rich off this. All we’re trying to do is change the conditions so that Illinois does not run such a horrible prison anymore in the future.”

Illinois spends more than a billion dollars a year on prisons, about $20,000 per year per inmate.

The conditions inside matter because the prisoners in Vandalia—they’re going to be released.

And like Louis Wilkins, a lot of them are getting angry.

Wilkins says he sometimes wakes up crying and can’t get back to sleep as his mind races over his experiences at Vandalia and the politicians and administrators he holds responsible.

Wilkins said, “Eventually they will have to answer to God. You know they might don’t see their punishment here on earth but they will one day, when they get in front of the maker they’ll see it.”

Wilkins says he often thinks of the people still imprisoned at Vandalia.

He says they may have committed crimes, but they should not be forced to live like that.

John Howard Association-Report from Vandalia