Read Some Of The Legionnaires’ Emails That Gov. Rauner Is Fighting To Keep Secret

By Dave McKinney, Tony Arnold

Read Some Of The Legionnaires’ Emails That Gov. Rauner Is Fighting To Keep Secret

By Dave McKinney, Tony ArnoldEugene Miller laid feverish and gravely ill in his bed at the Illinois Veterans Home in downstate Quincy. He hadn’t eaten for a few days, drifted in and out of consciousness, and winced in pain whenever nurses attempted to reposition him.

The adult children of the 86-year-old U.S. Army veteran consulted with the home and his doctor, according to his family’s account, and on Aug. 26, 2015, authorized the facility to make no extraordinary effort to prolong his life.

Shortly thereafter, a stunning phone call from the state-run facility arrived: Would Miller’s children agree to have him tested for Legionnaires’ disease?

The family approved and waited two days for the results. On Aug. 28, 2015, they learned he tested positive for the waterborne form of pneumonia. Along with that news came word from the home of three previous Legionnaires’ cases, dating back to July. Just four hours after the family got the test results, Miller died. Emails would later reveal that at the time of his death, the state had known for nearly a week that it was dealing with a Legionnaires’ epidemic at the home.

Immediately, Miller’s children wanted to know why they weren’t told earlier, and more importantly, whether their father’s life might have been saved if he’d been offered antibiotics sooner. To this day, they don’t have answers.

Stricken by guilt and anguish, Miller’s son, Tim, sat down a day later and composed a Facebook message to a county health official.

“My father is one of the two who passed away at the vets home. I know you are not responsible with how they handle things but it’s been really devastating to know that our choices for my dad’s care would have been different if we knew about the legionnaires [sic]. We did not find out … that my dad had it until four hours before he died,” Miller wrote.

“We have to deal with the fact that maybe we did not do all we could have. The situation was handled badly to say the least but the lack of communication in [my] mind killed my father, a hero who served his country only to die in its care,” the post read.

“I hope no other families have to sit and watch their loved one die in the same way we did and then to find out it may have all been prevented.”

The contents of Miller’s heartbreaking Facebook message circulated to the highest reaches of two state agencies under Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner’s control, including to the state public health director. WBEZ and state lawmakers separately have been trying to obtain emails relating to what would become repeated outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease at the veterans’ home. The disease has contributed to the deaths of 13 residents and sickened dozens more in 2015, 2016, 2017, and again this year. But the Rauner administration has fought to keep them secret.

Despite those roadblocks, WBEZ has obtained nearly 1,400 emails between state public health officials, local public health officials, and the state agency that oversees the facility in Quincy, which is about 310 miles southwest of Chicago along the Mississippi River in west-central Illinois. The records – including Tim Miller’s note — cover a period between the first outbreak in August 2015, up to this month. They are published below.

A joint Illinois House-Senate committee fought the Rauner administration for weeks to get access to emails related to Legionnaires’. The panel’s investigation into the state’s response to the outbreaks began after a WBEZ investigation in December. The series of reports by WBEZ shed light for the first time on the specific victims, what they went through, and how state officials delayed telling the public about the 2015 Legionnaires’ outbreak. Eleven families who lost loved ones are now suing the state for neglect, including the Millers.

What’s in the emails?

WBEZ received the emails through an open records request to the health department of Adams County, where the home is located. The county has been coordinating with the state to respond to the repeated outbreaks at the Illinois Veterans Home, known as the IVHQ. The exchanges show officials under stress and in full-bore crisis mode. At times, they appear not to comprehend the scope and danger of what would later emerge as a persistent public health crisis in Quincy.

The officials also focused on how the outbreak would play in the press.

The emails include internal discussions about how the media was portraying the Rauner administration’s effort to manage the outbreak. Spelled out in detail are “talking points” that state press aides used to cast a positive light on news coverage about the evolving crisis. Officials haggled over the wording of the first press release about the 2015 Legionnaires’ outbreak. A top epidemiologist at a Quincy hospital derided one draft as “smoke to cover peoples [sic] butts.”

The Rauner administration has not directly addressed what state officials wrote in the emails. But Rachel Bold, a spokeswoman for the governor’s office, said Tuesday they have been “deeply saddened by the loss of family members,” and they continue to work with the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to eliminate risks at the home.

“The safety of our veterans and staff at the Quincy Veterans Home is, and always has been, a priority for this administration,” Bold said in the statement. “We take very seriously the importance of protecting our nation’s heroes.”

Now, in a hyperpartisan campaign season, calls for Rauner’s administration to be more transparent have only grown louder, especially as the state has reported four more Legionnaires’ cases in Quincy in the past two and a half weeks.

What’s the fight over releasing emails?

In December and January, WBEZ filed open records requests with the Illinois departments of Veterans’ Affairs and Public Health seeking emails related to Legionnaires’ at Quincy. Both requests were rejected. But WBEZ is not the only entity being stymied.

In January, the governor’s office rejected a broader documents request from the special legislative committee investigating the outbreaks.

That month, Rauner’s top government lawyer, Lise T. Spacapan, informed the co-chair of the House-Senate panel, state Sen. Tom Cullerton (D-Villa Park), that potentially “hundreds of thousands” of documents might need to be reviewed, requiring “thousands” of work hours.

“The burden of your requests would outweigh even the significant public interest in this information,” Spacapan wrote to Cullerton.

Last Thursday, the governor’s office provided a box with approximately 1,000 heavily redacted paper emails to members of the legislative committee, Cullerton told WBEZ on Tuesday.

WBEZ obtained some of the emails the Rauner administration has been trying to keep under wraps from the Adams County Health Department. It’s unclear how many other emails exist about the state’s handling of the outbreaks, as the state refuses to release them.

When he was read several of the documents for the first time, Cullerton said, “From those emails, the only thing they’re doing is trying to cover their ass. Pardon my French.”

Family lawsuits: ‘It’s part of doing business’

Complaints from 11 families suing the state for neglect over the initial outbreak evince a common theme: They claim state officials didn’t give them enough information to make medical decisions that might have saved their loved ones’ lives. Within the cache of emails obtained by WBEZ, reaction to the Facebook message from Tim Miller offers a unique portal into how families were frustrated about a lack of information during the spread of Legionnaires’ in 2015.

By Aug. 29, 2015, the day Miller sent his Facebook message, at least three other residents had already died of Legionnaires’ and nearly three dozen people had gotten sick, according to a later report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Shortly after Miller sent it, the text of his Facebook message was emailed around. The original recipient in the Adams County Health Department forwarded his note to the public relations spokespeople for state Public Health Director Nirav Shah and state Veterans’ Affairs Director Erica Jeffries.

Shah spokeswoman Melaney Arnold quickly pivoted to messaging.

“It is understandable how upsetting this is, but for talking points — if pressed — testing/diagnosis for Legionnaires’ disease takes time,” she wrote in an email that same day. “As soon as we knew a diagnosis, we shared the info,” adding that “emotion is going to start driving the news stories, so I envision things getting much more difficult moving forward.”

Yantis went so far as to forecast lawsuits from the families of residents sickened by Legionnaires’.

“It’s part of doing business,” Yantis wrote. “We just need to be consistent and do the right things.”

‘Helps rebut the FB message’

On Aug. 30, 2015, a day after Miller sent his note, Yantis circulated a flattering Quincy Herald-Whig news story headlined, “Residents, family laud Illinois Vets Home staff as Legionnaires’s [sic] disease cases climb.” Shah and Jeffries were on the email chain, as were other state and Adams County officials.

“Coverage like this does not get much better,” Yantis said. “Talking points and responsiveness to the reporter help shape the story. Team effort.”

Shah, the state public health director, then responded with an apparent reference to Miller’s original Facebook note about his father’s death: “Great story. Helps rebut the FB message we saw yesterday. Thank you!”

On his own, Shah then forwarded that news clipping to the governor’s office, as did Jeffries, the Veterans’ Affairs director. “The good news is — the media and community have rallied behind the Home,” she wrote to then-state chief operating officer Linda Lingle, who appeared to be Rauner’s intermediary on the 2015 Legionnaires’ crisis. That note turned up in a batch of emails the governor’s office released to WBEZ in December.

Shown the state responses to his email for the first time, Tim Miller expressed outrage.

“What angers me the most about this situation, they’re putting all this effort into PR, giving each other pats on the back, ‘great job,’ ‘way to go team,’ ‘let’s come up with some canned statements,’ ‘let’s all be on the same page.’ Basically, it was like they drew a line in the sand and said, ‘It’s us against these grieving families,’” he said.

“To go through all that effort to rebut a grieving son’s Facebook message when we were burying my dad is inexcusable, and again, it just goes to show their concern at the time …was not for the families and the sick, but it was for how they looked and one-upping us and rebutting our grief,” Miller said.

The state responds

Arnold, who still works for the Illinois Department of Public Health, did not directly address the emails that arose from Miller’s initial Facebook message.

In a statement, she wrote, “We understand the pain and frustration of the families affected by Legionnaires’ disease and offer our heartfelt sympathies.”

She wrote that her department notified the Illinois Veterans Home “within 27 minutes” of learning of the second lab-confirmed case of Legionnaires’ on Aug. 21, 2015.

The current spokesman for the Illinois Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Dave MacDonna, said after receiving that notification, veterans’ home staff began reaching out to residents’ families to tell them about the outbreak. He also said Director Jeffries called and wrote victims’ families to express her condolences. Some families dispute that claim.

Yantis, who no longer works as a spokesman for the state, declined to comment.

In her statement, Arnold again referred WBEZ reporters to the same flattering Quincy Herald-Whig story from three years ago, which included “two individuals — a family member and an IVHQ resident — who were complimentary of the communication from IVHQ and the facility’s handling of the situation.”

The Miller family still has questions

Miller said he feels let down by the governor’s handling of the crisis in Quincy. Nothing the governor has done, including staying at the facility for a week in January, has explained why families were kept in the dark about Legionnaires’ in 2015 or given them closure, Miller said.

“I’m disappointed in how he tries to just make this situation no big deal, how everything is just sunny skies, blue skies, and terrific, and we’re still here two-plus years after my father’s death with the same questions we had,” Miller said. “Ultimately, that’s what we were looking for: a hero. Someone who was just going to say the truth, not candy-coat it, and just give us the information.

“And, we never got that.”

Shortly after Eugene Miller’s death, Jeffries did call and leave a message for Miller’s brother, Dennis, who was his father’s power of attorney. But Tim Miller said her call went unreturned because the family believed she would repeat the earlier claims of the home’s medical director, which they found offensive. According to the family’s account, the doctor said that Eugene Miller was dying anyway, and it didn’t matter if he had Legionnaires’.

“We, at that point, had heard our fill, and that was enough,” Tim Miller said.

A spokesman for the Illinois Department of Veterans’ Affairs did not comment on the family’s recollection of events after their father died, other than to confirm that Jeffries did leave a phone message.

The Millers’ experience was just one story during the early crisis when Legionnaires’ struck a facility that the CDC said lacked a formal water management plan and no Legionella-specific prevention plan. At the same time, other emails show state officials working hard to control the way the health crisis would be portrayed to the public.

Aug. 26, 2015: ‘There is no cause for alarm; this is a manageable situation’

A previously undisclosed email chain involved deliberations over the crafting of an Aug. 27, 2015 press release issued jointly by the state Veterans’ Affairs and Public Health departments confirming eight cases of Legionnaires’ at the home. By that point, the state had known for six days it had an “epidemic” on its hands.

The day before the press release went out, part of the email chain included a draft release and messaging bullet points, including one from Yantis, the Veterans’ Affairs spokesman, reinforcing that “there is no cause for alarm; this is a manageable situation and we are focusing talents, efforts and appropriate resources to meet the needs.”

The draft release ended with a rundown of how staff at the facility had cleaned ice machines and common bathing and shower areas, among other things, to try and kill the waterborne bacteria that causes Legionnaires’.

The head epidemiologist at Quincy’s Blessing Hospital, where many of the Legionnaires’ victims were taken for testing and treatment, questioned that phrasing in an email later that night.

“The last paragraph sounds like the cleaning is a new activity; did they not clean these before and what did they do as a result of the first cases in July? A smart reporter will eat the spokesperson alive,” emailed Dr. Robert Merrick.

“They should have had you write the release,” Merrick continued in his note to the hospital staffer. “Overall I think it is poorly written, confusing and in my view just a smoke to cover peoples [sic] butts.”

The press release later issued publicly by the state had the reference to cleaning removed.

Merrick declined to comment. Steve Felde, a spokesman for Blessing Health System, said Merrick’s opinion was not necessarily that of the hospital.

Later that day, while work on the first press release was happening elsewhere, the stress of the situation was beginning to show. In one exchange that involved a discussion about lab specimens, one state public health official quipped they’d already eaten quite a bit of chocolate. Shay Drummond, the former Adams County health official, responded: “I could use some chocolate right now!”

In her statement for this story, state public health spokeswoman Arnold said that “press releases are not intended to serve as notification to families.

“The intention of a press release is to answer questions about the outbreak, not to create confusion. Outbreak investigations are thorough, comprehensive, and take a significant amount of time to conduct. IDPH and IDVA issued the press release about Legionnaires’ disease at IVHQ when we had information needed to protect the public.”

Aug. 28, 2015: ‘Not continuing to put this in the media’s eye’

On Aug. 28, 2015, the day after the first state press release was issued, Arnold sent an email to Yantis at veterans’ affairs and to a top official at the Quincy home. The subject line: “Media strategy.”

Warning of a “big jump” in illnesses, Arnold nonetheless advised against issuing another press release but suggested simply putting the numbers on her agency’s website.

“We’re being transparent, but not continuing to put this in the media’s eye,” Arnold wrote.

Yantis agreed and laid out a series of theoretical “media triggers” that could prompt questions, including Legionnaires’-related deaths of residents or staff, residents being moved out of the home by their families and the emergence of potential whistleblowers, which he defined as “staff / residents purporting insider info on how [the Illinois Veterans Home-Quincy] and others screwed this up.”

As state officials discussed the PR of the crisis, more families of veterans’ home residents were getting worried, according to one email sent later that afternoon.

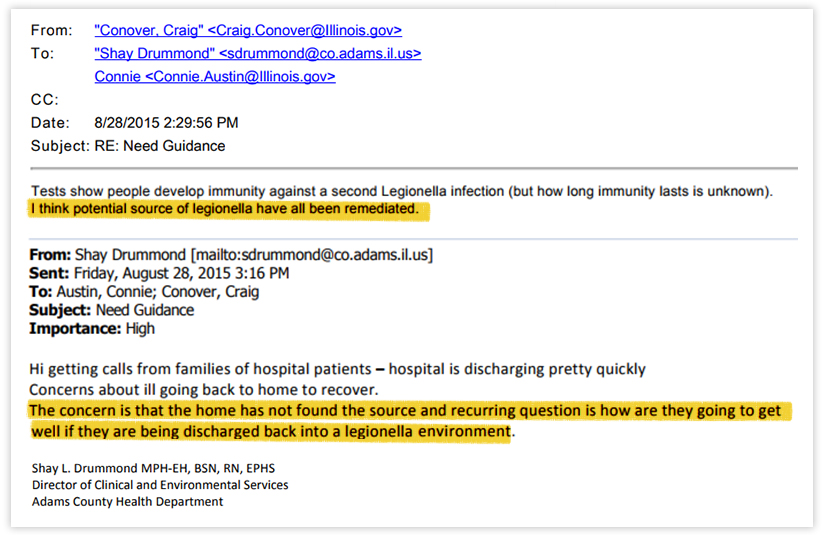

Drummond, with the Adams County Health Department, wrote to a pair of state officials that she’d been getting calls from families of patients being treated at the hospital. Their loved ones were being discharged “pretty quickly,” and they were worried about sending them back to the Illinois Veterans Home.

“The concern is that the home has not found the sources and recurring question is how they are going to get well if they are being discharged back into a legionella environment,” she wrote.

Craig Conover, with the state Department of Public Health, responded, “I think the potential source [sic] of legionella have all been remediated.”

Aug. 31, 2015: Bringing in the National Guard?

By the close of August, the state had confirmed at least four deaths related to Legionnaires, and more than two dozen people had been sickened. State and local officials began to acknowledge the problem could get bigger than they were equipped to handle.

In one email, Drummond, with the Adams County health department, broached bringing in the National Guard if the facility needed a “massive group effort” to help with the outbreak. A state Veterans’ Affairs official even suggested deploying Boy or Girl Scout troops, or college or high school students, with adult supervision.

Jeffries, a veteran who oversees the agency in charge of the Quincy home, showed some willingness to explore the idea of putting troops there, adding the state was already coordinating with the National Guard in case more medics were needed.

“We’ll have to think about the messaging for that though,” she said. “It might raise some alarm.”

Dave McKinney and Tony Arnold cover state politics for WBEZ. Follow them on Twitter at @davemckinney and @tonyjarnold.

Editor’s note: This story has been changed to remove a reference to TIm Miller’s voting record. Miller had told WBEZ he voted for Rauner in 2014, though public records don’t reflect him voting in that election.