Growing up in the Chicago suburbs in the 1980s and ’90s, Joe Principe was a kid filled with a little rage and plenty of restlessness. Like other teens, he was searching for an outlet in music that grabbed him by his adolescent collar.

“I got into punk when I was really young, probably fourth grade … I would go into [my sister’s] bedroom and steal her cassettes. And I remember coming across Dead Kennedys’ Plastic Surgery Disasters.”

The music spoke to him. Kids like Principe gravitated towards punk music in all its iterations — hardcore punk, grindcore, even pop punk — because punk meant freedom. It was about challenging the status quo and powers-that-be.

Principe started going to punk shows at a hodgepodge of Chicago-area venues: VFW halls, house shows, church rec rooms — basically any place that would take the young teenager. Like today, there weren’t any established all-ages music venues in the city.

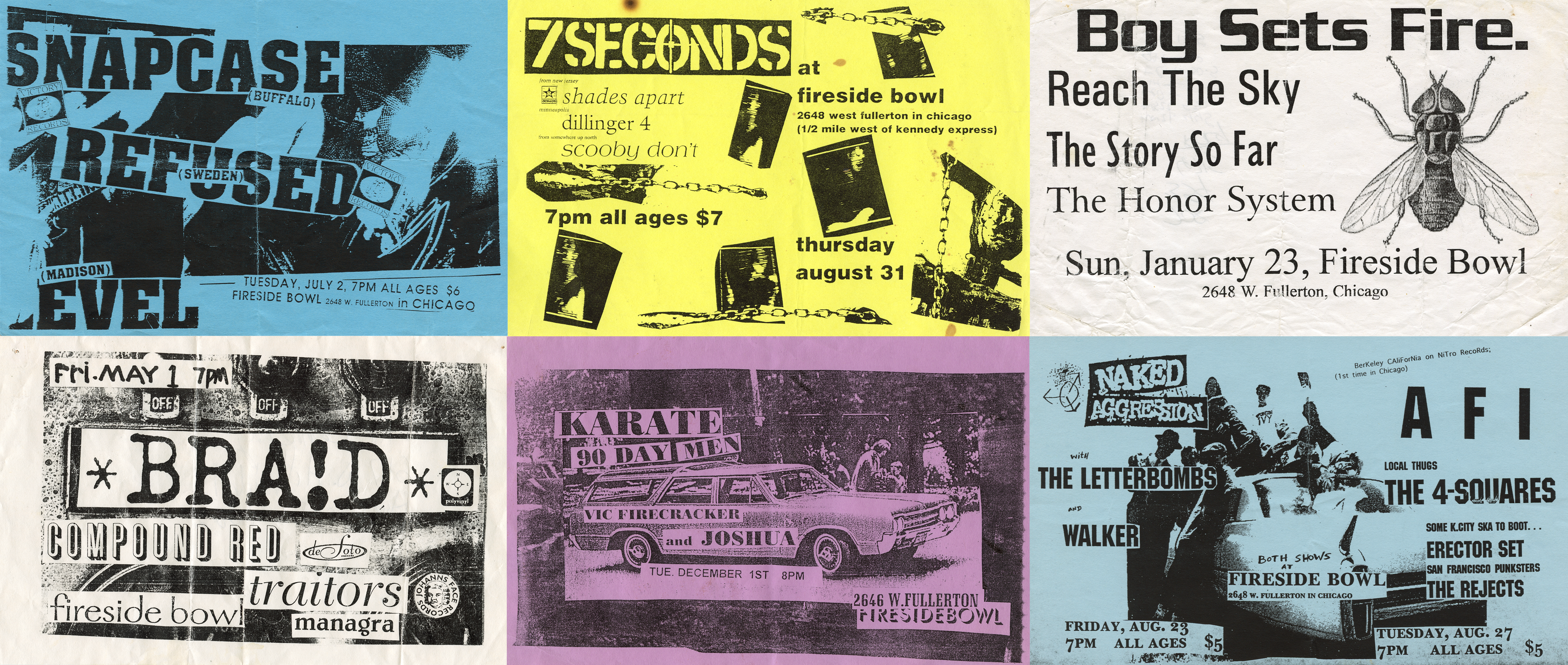

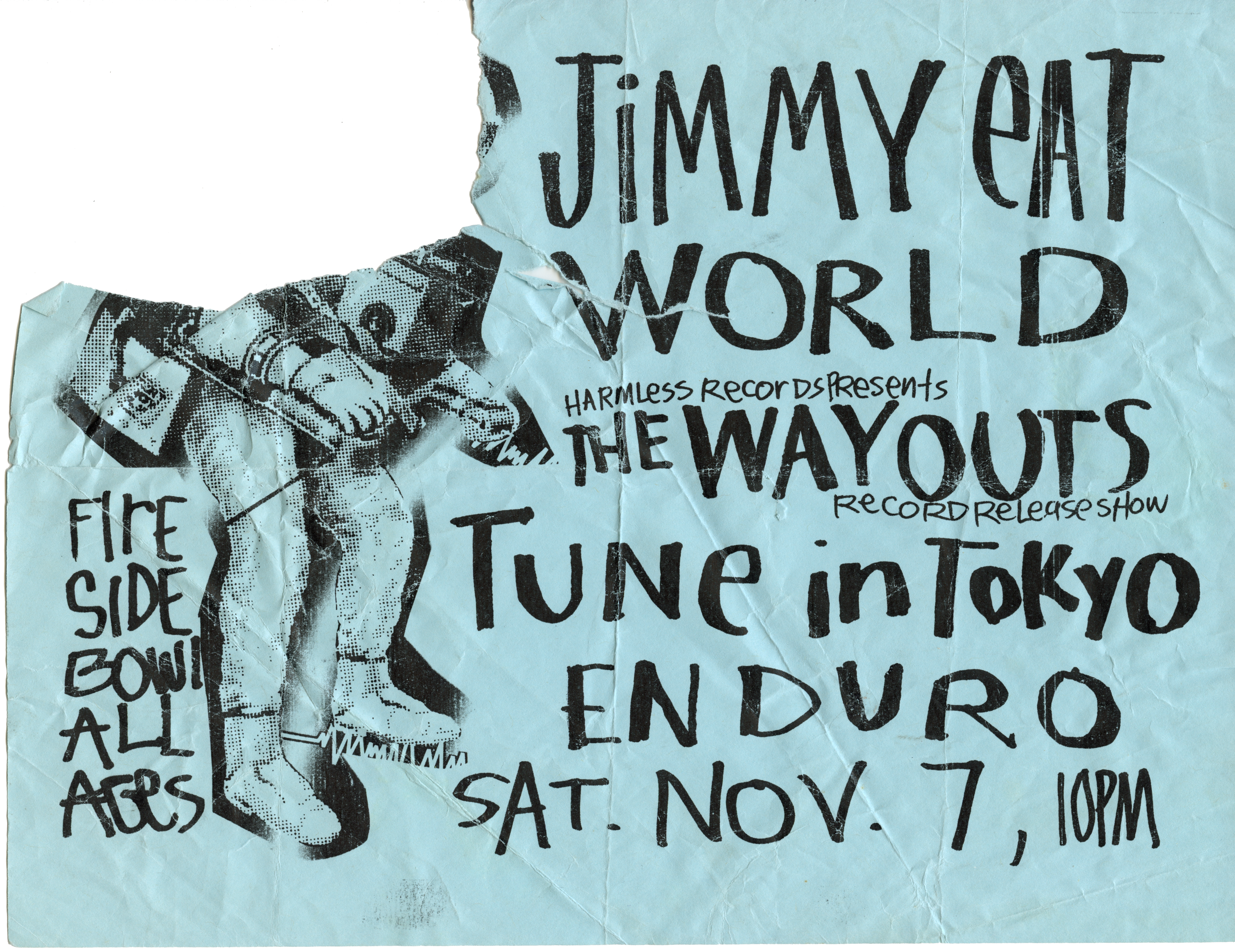

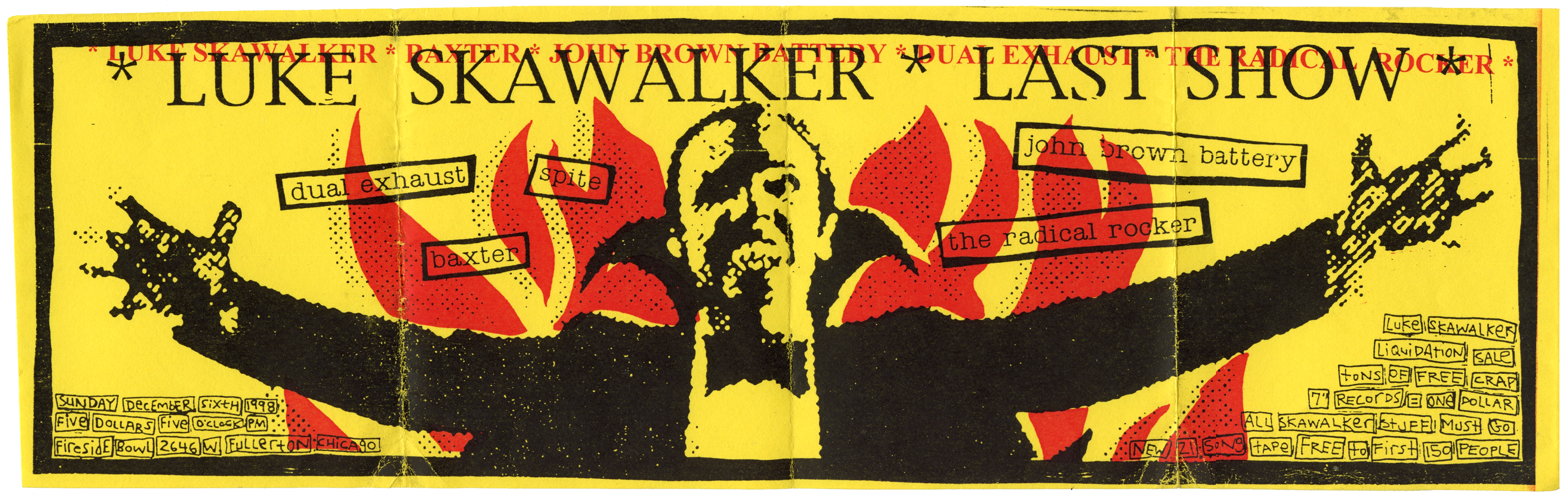

But there was a moment, nearly 30 years ago, when a run-down bowling alley opened its doors to punk musicians and fans from across the city. A whole generation of young people, Principe included, laced up their Doc Martens and came to the Fireside Bowl in Chicago’s Logan Square neighborhood to mosh, dance and shout along to the anthems of the era. For a little over a decade, the walls shook and the music blared at the rare all-ages punk venue.

The Fireside’s origins

With bowling on the rise as a popular pastime in the U.S., the building that’s home to the Fireside Bowl converted to a bowling alley in 1941. It’s believed the building was named the Fireside Bowl after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s radio addresses, the Fireside Chats.

According to Jim Lapinski, his father Rich Lapinski purchased the building in 1964. Lapinski said that his late father put a lot of love into the bowling alley, but he also ran it into the ground. By the early 1990s, the Fireside Bowl was on the brink of going under, and Jim Lapinski took over the business.

“It was kind of a rundown hole-in-the-wall … [it] was in really bad shape at that time,” Lapinski recalled.

A regular at the bowling alley named Russ Forster started organizing “disco bowl” nights. Forster was also part of the local punk scene, and ran a punk music label.

One day in the early 90s, he mentioned the Fireside to local musician Martin Sorrondeguy as a potential one-off show venue.

“He said, ‘There's this bowling alley, and it's about to go out of business or something,” Sorrondeguy remembered. “‘They're desperate to do stuff, and I think they'd be willing to do shows.’ And that was the first time I heard about the Fireside.”

“I think it was punk shows that really saved [the venue] and brought it back to life,” Sorrondeguy said.

Early days as a music venue

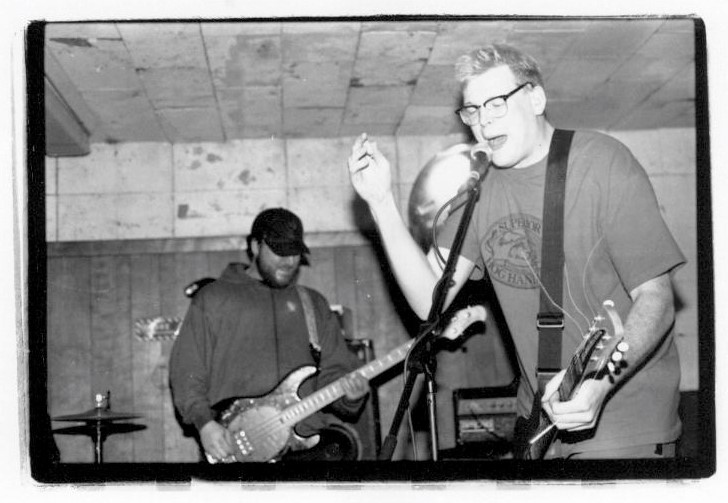

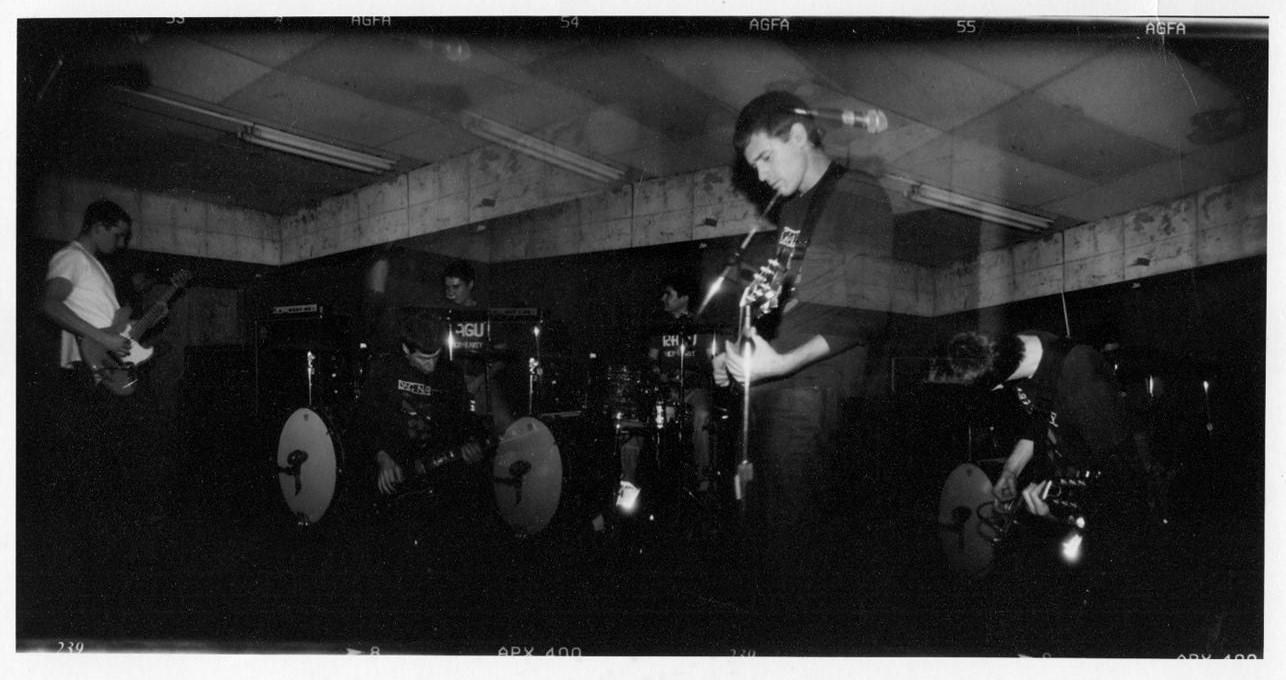

In some ways, the dilapidated interior of Fireside Bowl in the mid-’90s was a perfect fit for the punk ethos of the bands that played there. But it was nothing to write home about.

“Walking into Fireside, you had carpet, which was disgusting,” said Francisco Ramirez, a man who often worked at Fireside shows. “It smelled like smoke because everybody smoked. … There wasn't [sic] stage lights at the time, so they would just have those fluorescent lights on the whole time. So it was ugly. … And of course the bathrooms were horrible.”

One fan recalled a broken stall door on the floor of the women’s bathroom. She said she and another patron literally took turns holding the door up to give each other privacy.

Brian Peterson and David Eaves, both of whom did extensive booking around the city and the suburbs, approached Lapinski about putting together more regular shows at the Fireside.

“I didn’t have anything to lose at the time,” Lapinski said. “I couldn’t really put any money into the place.” So he took Peterson and Eaves up on their offer. “It kinda grew from there.”

Peterson in particular became closely associated with the Fireside.

“No matter what, Brian Peterson always made sure the touring band got paid,” Ramirez said.

He said even if there were a few people there, Peterson made sure touring bands got paid, sometimes out of his own pocket. Local bands would do the same and voluntarily give up their cut of the door to make sure the touring artists got at least gas money, if nothing else.

As things started to take off, Peterson realized he needed staff — including live sound engineers and people to work the door — to keep shows running.

Though a bowling alley might not seem like an ideal spot for a decent sounding live music experience, Elliot Dicks – who oversaw sound at the Fireside – said it wasn't as bad as you might think.

“For me, the Fireside was easy because it had that sort of a more dead sound…because it has acoustical tile ceiling... wood paneling walls,” he said. “I could always get the vocals up over the band at the Fireside."

By the summer of 1994, the Fireside started to become known more as a music venue than a bowling alley. Peterson and Eaves were booking shows several nights a week.

The Fireside was starting to hit its stride. Though on paper the venue operated as a hall that could be rented out (similar to a VFW) to bands, in practice it was a punk music destination at a bowling alley that was quickly gaining national recognition.

‘It’s the place where you grew up’

In the mid-1990s, bands like Green Day were topping music charts.

One of the many reasons young people were drawn to this music was it spoke to the angst, restlessness and isolation of being a teenager at the turn of the 21st century.

Joe Principe, the bassist for 88 Fingers Louie, and later for Rise Against, said the Fireside helped young people who were drawn to that music find each other. “It’s the place where you grew up,” he said.

“[The Fireside] was your punk-rock Cheers,” added Daryl Wilson. “Every day of the week, you had a place to go.”

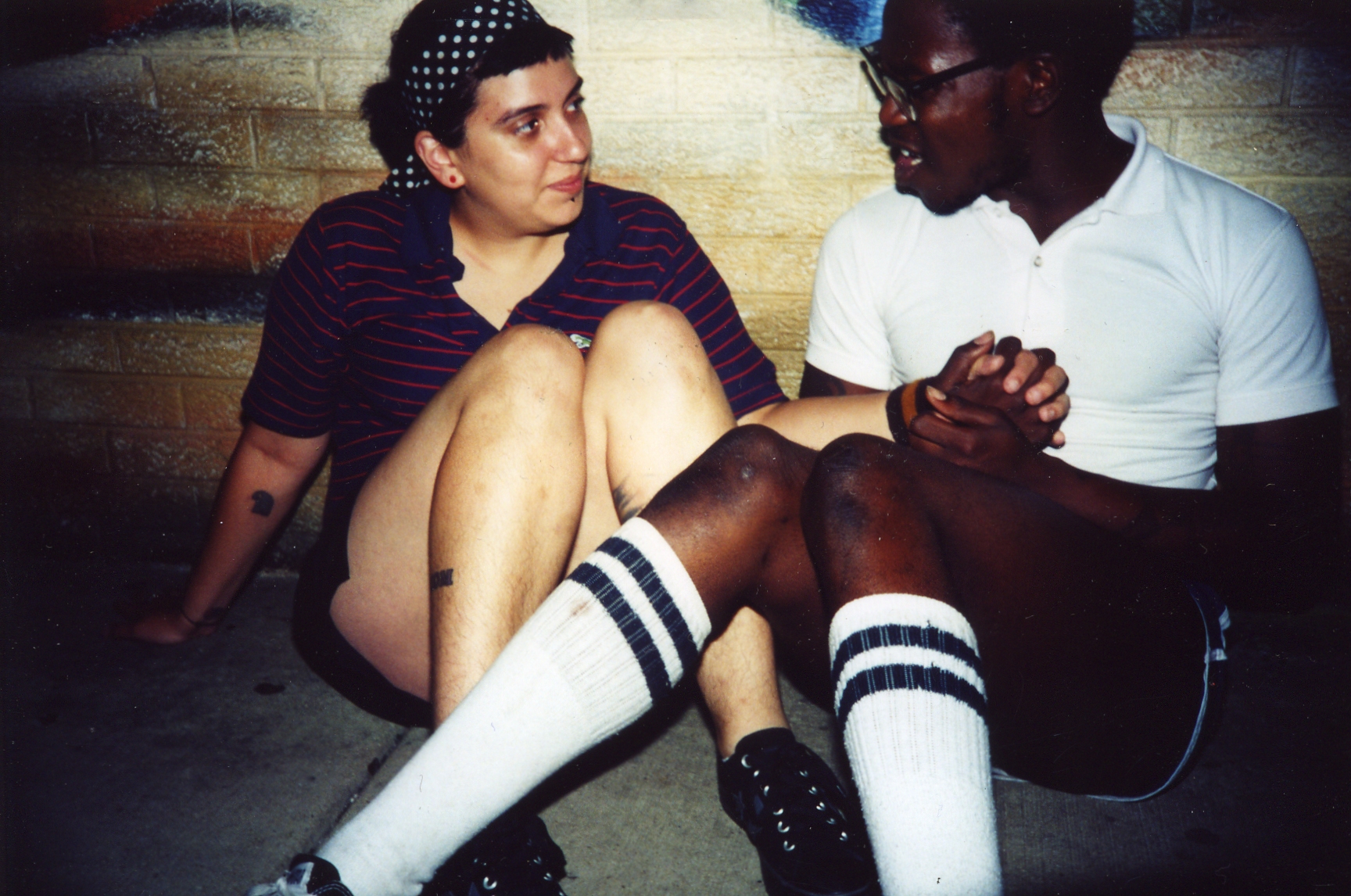

Wilson, the lead singer for the band The Bollweevils, said having a space in the city where he felt comfortable was no small thing. “As an African American kid who likes punk rock, that’s definitely [putting] you in one of the smaller brackets,” Wilson said. “You’re looking around for the kid who looks like me to let them know, ‘Hey, you’re accepted. You’re part of this.’ ”

While many North Side music venues tended to draw a majority-white audience, and the Fireside was no exception, shows there were often a reminder that the punk scene strived to be inclusive.

“The scene was very diverse, in terms of all the different students and tweens and teens who are converging on the Fireside,” said Alex White, who plays in the band White Mystery and goes by the stage name “Miss Alex White.” Back then, in middle school and high school, White attended shows and performed at the venue. “Black, Hispanic, queer, Asian — it was all identities kind of united just by the ability to hang out somewhere that was all ages, and people were listening to [everything from] hip-hop to punk to two-tone ska.”

Sorrondeguy had been on tour with his band Los Crudos and tested the waters by coming out as gay on stage at those shows. He finally decided to try it at the Fireside. “It was awkward. It was nerve wracking, but I did it,” he said. “There were little ripples that happened afterwards, and people who were a little homophobic [and] didn't like it.” But overall, “the response was really positive.”

White, who started going to the Fireside when she was 13, remembered her mother’s hesitancy the first time she went to the venue. “My mom goes up to the door guy, and she's like, ‘Is this cool? That I'm, like, dropping my kid off here?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, she'll be fine.’ ”

Sorrondeguy said the Fireside helped open up new audiences to bands like his. His band Los Crudos favored playing all-ages shows so all people who were into punk and underground music could access them.

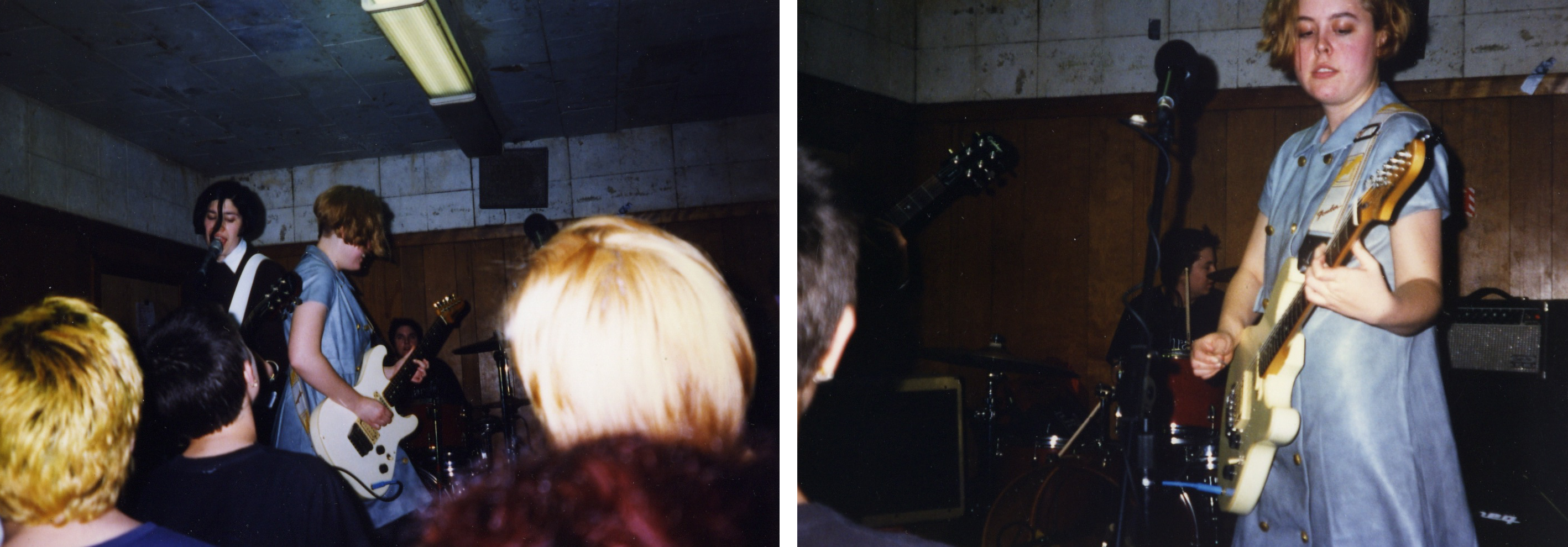

The venue also served as a familiar stop to the burgeoning ’90s riot grrrl movement, with bands like Bikini Kill and Sleater-Kinney coming through the space.

Ramirez, a regular at Fireside shows, said things weren’t always peaceful at the venue. Occasionally, skinheads would show up at the Fireside, and they’d have to choose between getting out and getting beaten up.

“Someone would come up to me and say, ‘There's a guy wearing Nazi pins. He's gonna get jumped,’ ” remembered Ramirez. “So I would go to him, like, ‘Hey, listen, this is not a good place for you to be. A lot of people are angry that you're here. I'm gonna give you your money back, but you need to leave.’ Obviously, I wasn't happy that they're there. But I didn't want somebody to get destroyed at the club because they're an idiot.”

People kept each other safe at the Fireside in other ways. They “self-policed”: people in the scene kept an eye out for potentially dangerous behavior. “We’d go up to someone and say, ‘Hey, you’re way too drunk for this,’ or ‘you’re way too violent for this,’ ” Fireside regular Christopher Gutierrez explained.

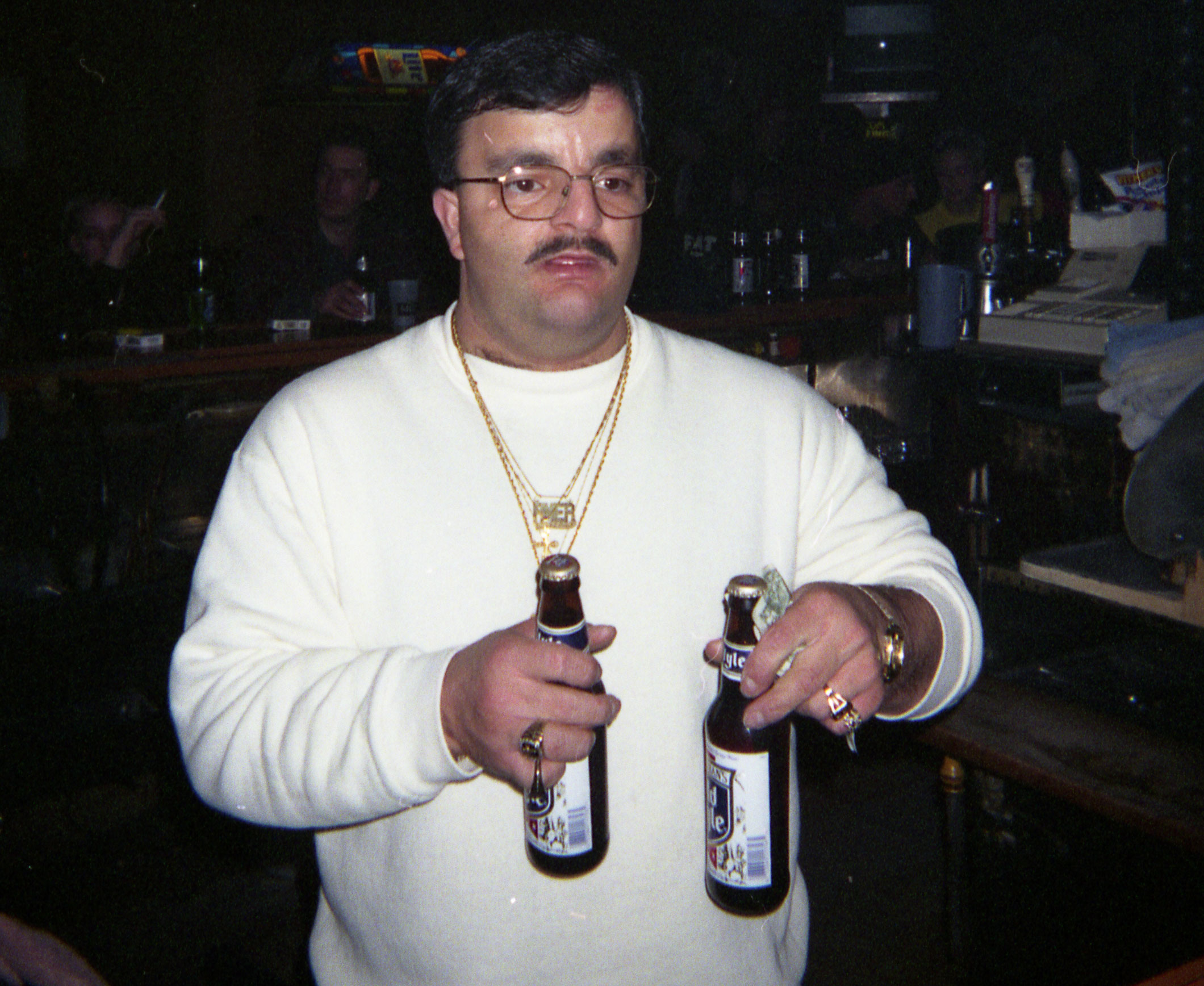

The Fireside was full of recognizable personalities. One of the most curmudgeonly fixtures was “Hammer,” a man mostly known by his nickname.

“[Hammer] was a staple,” Wilson explained. “If he wasn’t there, you knew something was wrong.”

“He was a terrible bartender,” Lapinski said. “He didn’t know how to make a drink … just gave you whatever he felt comfortable making.”

Hammer was a neighborhood kid who’d come around the bowling alley looking for odd jobs. After that, he never really left.

Like all great venues, it was the people — bands, bookers, doormen, sound engineers, bartenders and, of course, regulars in the audience — who made the Fireside what it was.

A slow demise

By 1996, bigger acts were consistently coming through the Fireside. “It became a go-to stop on people's tours,” Principe said. Blink-182, My Chemical Romance and Taking Back Sunday all played in the cramped bowling alley at one point or another.

“I remember the cops came in. We had a big show. And they were just like, ‘You need to get these people out of here within 10 minutes,’ ” Ramirez said. “So we … stopped the show. Made an announcement. We had people go out the back door, and we were like, ‘Hey, they're gonna come and do an inspection. [But] as soon as they leave, everybody's coming back in.”

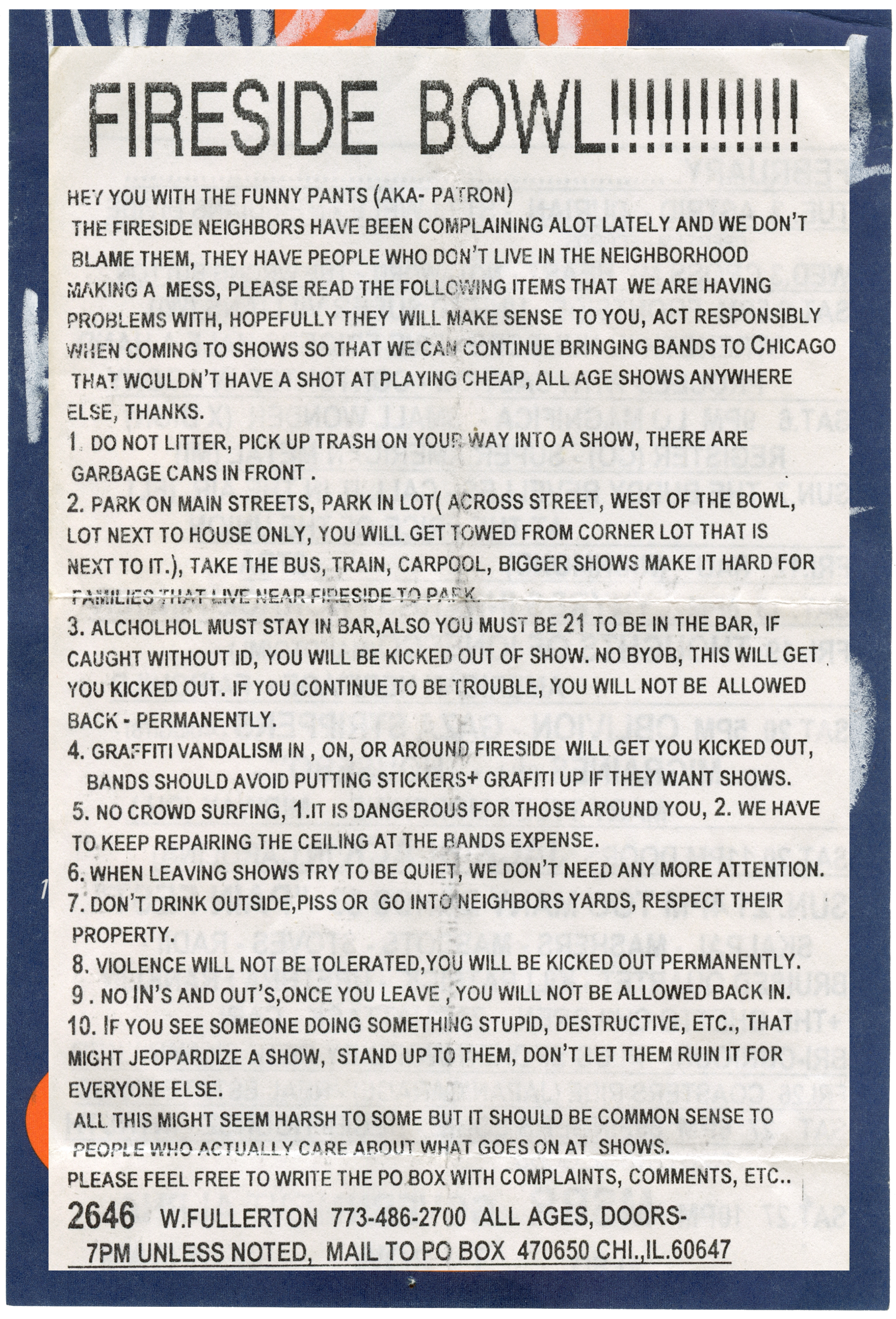

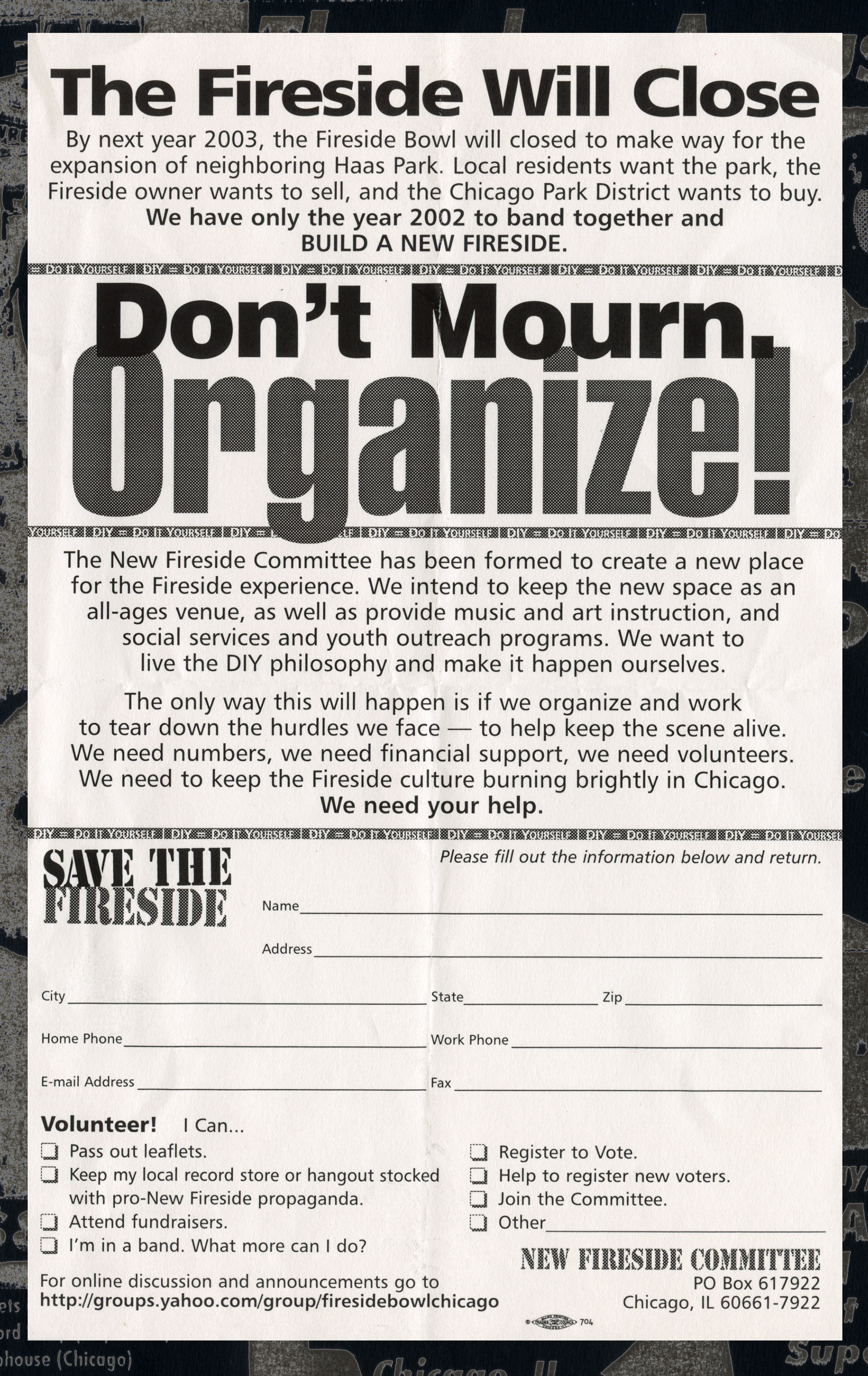

Neighbors started complaining about noise from the venue, underage drinking, parking issues and public urination.

In response, bookers started passing out flyers explaining rules to showgoers: no littering, no graffiti, no going into neighbors’ yards.

While small improvements to the building were made over time, the constant threat of being shut down by the city disincentivized Lapinski from giving it a proper facelift. According to several people we spoke with for this story, by the early 2000s, the air conditioning had given out, making mosh pits at Fireside extra sweaty.

“It was grimy, it was rundown and it was small,” said Gutierrez of the venue during these years. “It had charm, though.”

Despite the money coming in, Lapinski said he was getting tired of the risks that came with running a club. Even if he won his battle with the city, he craved a simpler, more predictable day-to-day work schedule that would come with reverting the venue back to a full-time bowling alley.

The legacy lives on

By the end of its decade plus run, the Fireside’s time as a music venue had largely come to a close.

On August 20, 2004, Fireside Bowl was set to host a double show: MU330 a ska punk band from St. Louis followed by a garage rock band, according to Ramirez.

“I was a manager at the time, and the other manager came in and he’s like, ‘Hey, we got to pull the safe down. We’re closing down [at the end of the night],” said Ramirez.

According to people we spoke with, someone made an announcement from the stage that this would be the final night of music at the Fireside. Word spread fast following the sudden declaration, and people rushed in for the Fireside’s final show.

“The place filled up and things went missing: bowling pins, trophies, bowling balls,” Ramirez said. “I walked out with a trophy and a bowling pin.”

![‘I eventually moved just down the street [of the Fireside],’ said Fireside regular Rebar A. Rakstad, ‘so there would be times that my roommate would call me and say, 'They're about to go on!' and I would hop on my bike and head over.’](https://cdn.wbez.org/image/142e929da460e4bbfed9317ed2055972)

Everyone wanted a piece of the place. At the same time, those who had been part of the punk scene for a while were familiar with the ephemerality of beloved venues.

“We were used to places disappearing,” Sorrondeguy said.

Today, people of all ages can still catch shows at venues like Subterranean in Wicker Park and Bottom Lounge in the West Loop. Any Chicago business that’s licensed to have live music (most commonly through a public place of amusement license) can technically allow people of any age into their space. While most concert venues have licenses to serve alcohol and allow entry to patrons of all ages, it is extra work for business owners. Tavern licenses require businesses to limit entry to patrons 21 and over.

Memories of the Fireside during its heyday live on in those who spent time there. “The experiences [the Fireside] gave to thousands upon thousands of people … made that place legendary,” Gutierrez said.

The Fireside will forever be a spot where countless bands got a foothold in the indie music scene. It was a venue where Chicago’s up-and-coming bookers learned how to get paid and make it in the music world. It was a DIY networking space for a whole generation of punk musicians. It’s where people made lifelong friends and found a space to call their own.

“It's still a punk rock venue,” Wilson said. “It's written in the walls. It's in the carpet. It's in the dankness of the room. It's even in the bathroom.”

“You walk through this Halcyon dream of the Fireside and go, that really happened and you were part of it.”

Joe DeCeault is a Senior Producer for Curious City.

This story was inspired by a listener's question about all-ages music venues in Chicago.