Walking around Chicago in the 1940s, you’d see the Wrigley Building and the Chicago Board of Trade dominating the skyline. Prohibition was over, and taverns boomed. Jazz clubs, theaters and dance halls were places people went to enjoy themselves.

But if you walked into Schulien’s, at 1800 N. Halsted, you would have happened upon a burgeoning form of entertainment: close-up magic. The German restaurant was where you could find Matt Schulien doing card tricks with a cigar in his mouth and a grin on his face. And while close-up magic had long existed, this particular blend of characteristics — sleight-of-hand magic, incorporating humor, in a restaurant or bar setting — was becoming known as Chicago-style magic, in large part because of Schulien.

When Curious City got a question about the history of Chicago magic, we spoke with half-a-dozen local magicians and historians, watched close-up magic in action and got a behind-the-scenes tour of the Chicago Magic Lounge. We learned how Chicago popularized a particular type of magic — now known the world over as “Chicago style” — and spoke with people continuing the tradition.

The making of Matt Schulien

Matt Schulien’s father, Joseph Schulien, came to Chicago from Germany just after the Great Chicago Fire. According to Anne Mickey, Matt’s granddaughter, the family opened a German restaurant and saloon called Schulien’s — often referred to simply as “1800” because of its location at 1800 N. Halsted — in 1914.

Matt learned his first card tricks sometime in the first two decades of the 20th century. The stories differ as to how exactly it happened. In one version of the tale, he learned sleight of hand from renowned Chicago-born magician Harry Blackstone. In another, an “old timer” taught him the basics when he was a child, at the first saloon his father owned. A third version tells it that he learned close-up magic while serving in the First World War. “There could be some truth in all of it,” Mickey said.

Joseph initially discouraged his son from doing magic at the restaurant. But eventually he came to see that his son’s tricks weren’t bad for business; on the contrary, they brought customers in. Reluctantly, Joseph allowed Matt to start doing magic in earnest at Schulien's. But it wasn’t until after Prohibition ended that Matt really became known for magic, according to Joey Cranford, founder and co-owner of the Chicago Magic Lounge.

Each night at Schulien’s, Matt settled into his craft. “He opens his shirt, pulls down the knot of his tie, rolls up his sleeves, settles all 320 pounds comfortably in his chair, and in two minutes has everybody in the place clustered around him,” Frances Ireland Marshall, a fixture of the Chicago magic community in her own right, wrote in an article for the book The Magic of Matt Schulien.

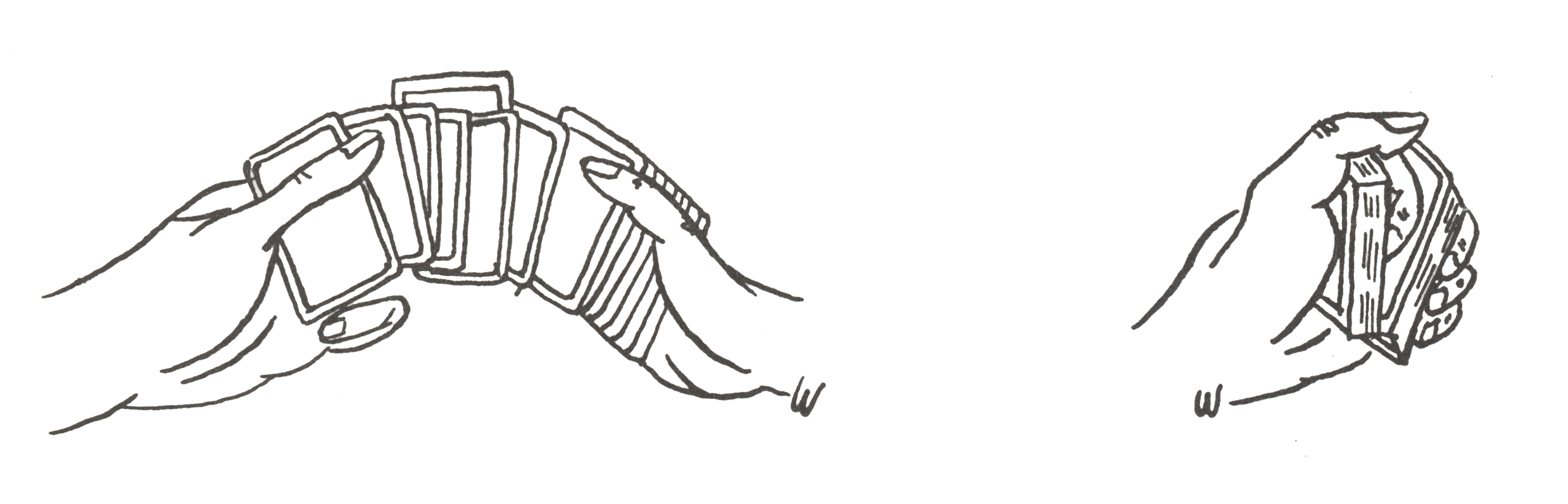

Matt became known for a trick called “card to wall,” in which he asked someone to choose a card, returned the card to the deck and then threw the deck of cards at the nearest wall. When all the cards had fallen to the floor, only the person’s chosen card remained, thumbtacked to the wall.

Matt wasn’t the best magician in the city, but as Marshall tells it, he was the most entertaining. “Matt knows that the big thing is to have fun,” she wrote, “and his patrons are so busy having fun, they pay little attention to tiny things like an ace stuck under Matt’s thigh.”

“[W]here they have fun, they come back,” she continued. “They came back to Schulien’s in mobs.”

A different kind of magic

By the time Schulien learned his first card tricks, magic had been around for a long time and taken many forms.

During their shows, stage magicians performed illusions. Blackstone, for example, was known for making a bird cage disappear. These magicians regularly used live animals and sometimes had assistants who could be sawed in half or levitated off the ground. They often had a serious demeanor and sometimes took on an exoticized persona. The audience watched from a distance in their seats.

When these magicians did sleight-of-hand card tricks, it was usually before the show, to entice people to come to the main event. “You'd see these magicians at a hotel lobby, and they'd be entertaining with some close-up magic,” explained Cranford. “[They’d tell people watching them,] ‘If you think that's cool, wait until you see me levitate an elephant next door.’ ”

But to Matt Schulien, close-up magic was impressive in and of itself. He made it the main act. All he needed was a chair, a table and a deck of cards.

Additionally, he changed people’s idea of who could do magic. “He always had a big, fat cigar hanging out of his mouth,” Anne Mickey, Matt’s granddaughter, said. “And he didn’t know a stranger.” He was a far cry from the stereotypical magician of the time: thin, serious, with a top hat and furrowed brow. According to Marshall, Matt used his figure to his advantage when doing magic. “He uses the crease between his belly and his leg (usually the right side) to hold cards, knives, etc., both coming and going,” she wrote.

Finally, Matt changed where magic was performed. He helped start a movement of people doing magic in restaurants and bars. And there was a certain egalitarian aspect to the restaurant venue itself, which as Marshall described was frequented by factory workers and Broadway actresses alike. “Old customers have come there for the wake of a mutual friend, and new fathers have dropped in to give Matt a cigar,” she wrote. “It makes no difference to Matt, rich or poor, nobodies or celebrities — he has the same smile, the same handshake for all.”

It was these elements — close-up magic, often incorporating humor, in a restaurant or bar setting — that would become known as Chicago-style magic.

Chicago magic’s golden age

During the 1940s through the ’80s, Chicago-style magic came into its own, and magic bars and restaurants proliferated.

The New York Lounge, a significant venue for close-up magic, opened in 1945.

Another magician who performed at the New York Lounge was “Heba Haba” Al Andrucci.

Jan Rose, a longtime Chicago magician who saw Andrucci perform, described a trick he would do where he would write someone’s initials on a sugar cube, and then drop the sugar cube into a drink. Meanwhile, he’d start a card trick where he’d ask the same person to choose a card and return it to the deck. “All of a sudden, everything was gone,” she said. “The card was gone, the sugar cube was gone.” Al would ask the person to open their hand, and there were their initials, written on their palm in ink. “It was funny, and amazing. And it would knock you off your feet,” Rose said.

Magic, Inc., a long-running prop shop that previously operated under the name Ireland Magic Company, moved to Lincoln Ave. in 1963. Frances Ireland Marshall, co-owner of the shop, was involved with a local chapter of the Magigals, composed of women magicians. Magic, Inc. became a popular hangout for magicians, a major publisher of books by local magicians and the location of a series of talks and workshops on magic.

Little Bit O’Magic, a South Side restaurant that went through several incarnations, first opened in the 1970s.

According to Joey Cranford of the Chicago Magic Lounge, the demise of these long-standing venues was driven by several factors. “Cable television was happening,” he said. “And stand-up comedy was happening. … I think there was a case of just a perfect storm of other things to do, other places to go. And then the sad mortality of the bars themselves.”

Beyond close-up magic

Not all Chicago magicians did close-up magic, even during the 20th-century golden age.

Walter King Jr., who performs as the Spellbinder, first learned magic from watching television shows featuring the art form from his living room on Chicago’s West Side. “Magic for me is theater,” he explained. “When I began doing magic, when I was a kid, the process of creating it was just as interesting as the effect.”

King performed magic at dance clubs all over Chicago’s South Side starting in the 1980s. He had to come up with tricks that people could enjoy without being close to him and in the midst of a lot of distractions.

“I was known to do a full 45-minute act without talking, without speaking a word,” King said. “See, because you're at the club now, and people want to dance, and so it was all music — just one track after another. And I would just create these routines off of the beats.”

But King wasn’t the only illusionist performing at Chicago dance clubs in the ’80s. There was one particular magician with whom he developed a rivalry. “He called himself Top Hat,” King said. “He never told anybody what his real name was.”

According to King, he and Top Hat had their own clubs at which they performed. But the rift between the two came to a head in June 1982, when King was featured on the front page of the Chicago Defender. “He was ticked,” King said of Top Hat. “So that became the rivalry.”

Top Hat and King eventually became close friends and fishing buddies. And though the type of magic he specializes in is different from that of “Chicago-style” magicians, King said he’s found a home at the Chicago Magic Lounge amongst magicians like Al James and Jan Rose. “I'm glad to be able to be a part of that family,” he said. “They call me the house illusionist.”

A new era

For the past few years, Chicago has arguably been in the midst of a magic renaissance, helped along by the Chicago Magic Lounge and a slew of other shows and venues.

On a recent Tuesday night, the spirit of Chicago-style magic was alive and well at the Logan Arcade. There, magician Justin Purcell sets up every other week at a small table with a Venmo QR code for tips. People sit on the bar stools in front of him or hover behind their friends, watching.

Purcell has a deck of cards, a few cups, ping pong balls and tennis balls. He does tricks created by people like Ed Marlo, a famous Chicago card magician. “It does make you feel connected to history,” he said, “because you read a trick in a book from the 1890s, and then you go and you try it on people now. And they're as amazed now as they were 130 years ago.”

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Logan Arcade (@logan_arcade)

By bringing magic to ordinary venues and performing in a no-frills way, Purcell and magicians like him are following in the footsteps of Matt Schulien.

As a small crowd forms around him, some say they came to the Logan Arcade just to see Purcell. Others encountered him unexpectedly. It isn’t long before the onlookers are shrieking with delight, turning with wide eyes to their friends — incredulous as to how Purcell has defied all laws of physics just inches from their faces.

Purcell keeps going, making cards seem to disappear from the deck and reappear underneath a volunteer’s hands, which are pressed against the table. “That’s how you know the magic is real,” he says.

Maggie Sivit is Curious City’s digital and engagement producer.

Ari Mejia is Vocalo’s audio and community storytelling producer.