How A Rat Balloon From Suburban Chicago Became A Union Mascot

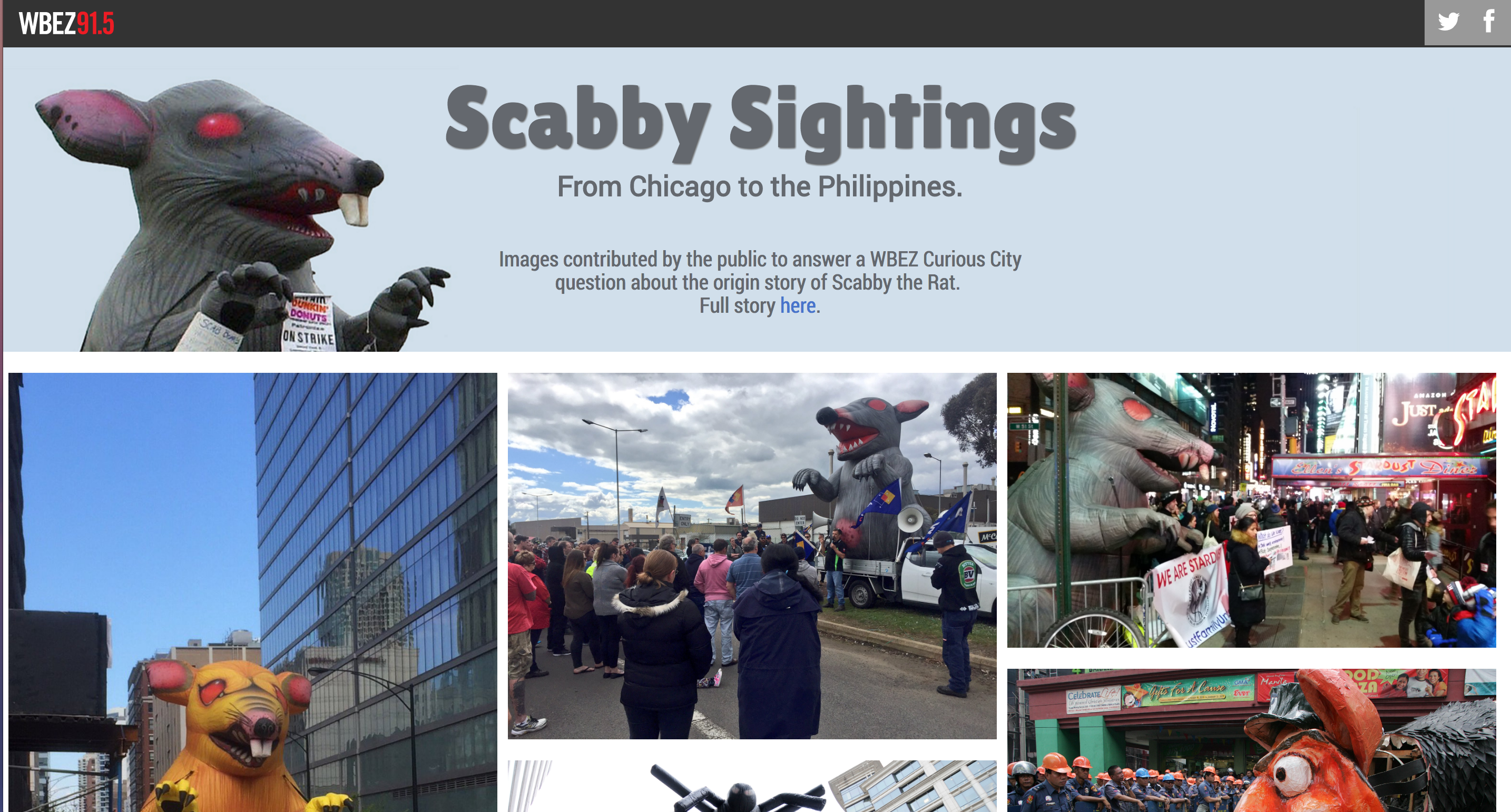

Scabby the Rat is now common on picket lines around the world, but the balloon started in Chicago’s historically blue-collar suburbs.

By Max Green

How A Rat Balloon From Suburban Chicago Became A Union Mascot

Scabby the Rat is now common on picket lines around the world, but the balloon started in Chicago’s historically blue-collar suburbs.

By Max GreenLarge inflatable-rats, with their claws out and lips curled into a snarl, have become a common sight on picket lines throughout the Chicago area.

The balloons, which range in size from six- to 25-feet tall, are usually gray or yellow. And almost all look like they are ready to attack.

The rat balloons prompted Curious Citizen Phillip Williams to ask: How did balloons become a part of union strikes? When do they decide to bring out the rat?

The rat balloons, nicknamed “Scabby,” started in the Chicago area in 1990 and have grown into a worldwide symbol for union strikes. But the balloons aren’t without controversy. From the picket line to the courtroom, employers have tried to snuff out Scabby many times.

The birth of Scabby

Ken Lambert, a former organizer with the International Union of Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers, says he was searching for a way to draw more awareness to a 1990 picket in north suburban Chicago.

“I wasn’t getting much attention, which is what a picket line is trying to do,” he says.

Then, Lambert says, he saw a sign from above. Literally.

That sign, off Interstate 294, was a billboard for Big Sky Balloons and Searchlights in Plainfield.

Lambert says he was so excited about the idea of bringing a large balloon to a protest that he called the balloon-makers from his vehicle on the union’s “bag phone” — a large, early cell phone that came in a bag.

“They picked up and we started to discuss the possibility of a rat,” Lambert says. “They didn’t have one, of course, but eventually we got together and developed what (became) Scabby.”

Lambert says he chose a rat because the animal has long been used as a symbol to call out those who oppose unions. Fellow organizer Don Newton helped secure the funds for the first balloon, Lambert says.

“They created this balloon, other unions in the area liked it and started using them, and it kind of took off from there,” says Mike Lowery, the secretary treasurer of the Illinois chapter of the bricklayers union.

Lowery says the union now has about a dozen rat balloons that often join workers on the picket lines.

The balloon makers

Peggy O’Connor and her husband co-own Big Sky Balloons & Searchlights. She says Lambert’s request was unusual at the time.

“I remember (my husband) saying there’s a guy who wants a rat balloon — and he wants it really ugly,” O’Connor says.

She says now the company sells a handful of the rat balloons every month to unions coast to coast.

“After the rat became successful, and was seen across the country, there were other unions that wanted to do different things,” O’Connor says. “So we designed a greedy pig with a big fancy vest and a pinky ring.”

After the pig, they made a “fat cat” in a suit, smoking a cigar and holding a union worker by the neck. The balloon signifies greedy contractors keeping unions in a chokehold, O’Connor says.

O’Connor says the company now makes more than 250 kinds of balloons for occasions like graduations, business openings and birthday parties, but they have about a dozen variations on the protest inflatables.

She says her favorite animal balloons are the less intimidating ones, like the pink gorillas, but Scabby is a special point of pride for the company.

“Scabby the Rat has almost become a staple of the picket lines, and that makes me proud … I’ll be driving up and down Route 59 (in Plainfield) and see one of our Scabby the Rat balloons and I’m like, ‘Okay, that balloon probably came from Plainfield, went to Massachusetts, maybe the east coast, and now it came back here.’ It’s kind of nice.”

Scabby in the courtroom

Lowery says when Scabby comes out, controversy often isn’t far behind. He recalls one time when a contractor attacked the balloon.

“He got so mad, he pulled a knife and he stabbed Scabby and brought him to the ground,” Lowery says.

Scabby’s presence on the picket lines has not only incited violence, but has been the subject of numerous lawsuits.

The legality of using Scabby as a form of union protest has been contested, with many of the rulings relying on the interpretation of the 1935 National Labor Relations Act. The act ensures rights for striking unions to picket the location of an employer or contractor, while also protecting nearby companies or other organizations employers from being targeted.

Since the balloons became prominent, a number of those targeted by unions with balloons have turned to the courts with hopes of proving the rat is not a tool for free speech, but a weapon for intimidation and slander.

For example, in 2014, a New York City contractor filed an injunction against a union it claimed broke a collective bargaining agreement.

The agreement prohibited “strikes, walkouts, picketing, work stoppages, slowdowns, boycotts or other disruptive activity of a similar nature at a job site.” The agreement didn’t specifically mention rat balloons.

The lawsuit, however, claimed the workers violated the spirit of the agreement by “posting an inflatable rat or similar sign or device” at a job site.

But a judge disagreed.

“It is abundantly clear that Local 78 has a constitutional right to use an inflatable rat to publicize a labor dispute,” a district judge wrote in the filing for that case. “(The) plaintiff argues that the use of the inflatable rat is ‘disruptive’ to (its) business because its clients do not like the inflatable rat.”

The judge concluded if an inflatable rat doesn’t cause work stoppages at a particular site, the union is well within its rights, and allowing a business to prohibit a union from engaging in speech that is harmful to the plaintiff’s image would “completely eviscerate the First Amendment rights of the union.”

Lowery says he firmly agrees with rulings like this.

“We’re very careful about exercising our First Amendment rights and making sure we’re doing everything properly,” Lowery says. “But usually on the first day of a picket the police are called, usually the police then inform the owners that (the picketers are) well within their rights to use the public way to express their sentiments.”

Scabby’s legacy

After decades on picket lines around the world, Scabby has become a mascot for unions, said Mike Volpentesta, a current member of the bricklayers union.

Volpentesta recently held a homemade sign at a Bridgeview picket, where about a dozen workers were protesting what they called unfair wages.

“People come by and want to take pictures with their kids and (Scabby), and we welcome that,” Volpentesta says. “But we also have literature we hand out to help them understand what it represents and why we’re out here.”

Lowery says Scabby accomplishes what the organizers who designed the balloon set out to do decades ago — make people stop and take notice.

“It’s kind of a fun way to publicize our protests and draw attention to what we’re doing out here,” he says. “We get a response.”

But Lowery says just because Scabby shows up doesn’t mean the union will achieve its goals.

“I don’t know if (the rat) necessarily helps solve our problem, but I think we get more attention,” says Lowery.

More about our questioner

Phillip Williams, who lives in Hyde Park and has been in Chicago for almost 20 years, says he has personal ties to Midwestern unions.

“I used to live in the Detroit area and worked in a Ford plant,” Williams says. “I was part of the United Auto Workers union for a while, and my grandfather was very instrumental with labor unions and civil rights in Michigan.”

He says he’s been noticing the balloons for years.

“I take pictures for fun, and I was ending up with pictures of all of the rats and pigs and fat cats,” Williams says.

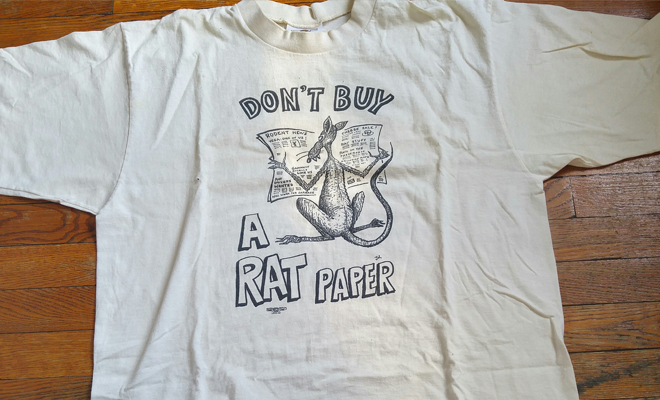

He says he first remembers seeing unions using the image of a rat decades ago, when he bought a t-shirt in support of a newspaper strike in Detroit.

Max Green is an independen