After deaths, state rep says Indiana is neglecting child protection agency

By Michael Puente

After deaths, state rep says Indiana is neglecting child protection agency

By Michael PuenteMonths after three young children died in a Hammond, Indiana house fire, a veteran Indiana lawmaker says the state has deprived the Department of Children Services of much-needed funds in order to ‘pad’ its budget surplus.

The charges raise fresh questions about the ability of the agency to carry out its mission of protecting children from abuse and neglect.

In the Hammond case, six-month old Jayden, 4-year-old Dasani Young, 4, and Alexia Young, 3 all perished. Two other children managed to escape the fire, with their father Andre Young credited for saving their life.

Several parties, from a juvenile judge to the city of Hammond to the birth parents themselves, have been criticized for not preventing the deaths. But many wonder how DCS allowed the children, who were living in foster care just months prior to the fire, to return to a home with no running water, heat nor electricity.

“Maybe the whole system, the laws failed these people,” says DCS Director Mary Beth Bonaventura. “Could we have done things better? Probably. Again, I don’t know the case intimately. I wasn’t the judge. I didn’t hear the evidence.

Bonaventura was appointed head of Indiana DCS in March 2013 following the ouster of the previous director over an ethics scandal.

“I think without question this is the most important job in the state,” Bonaventura told WBEZ in an exclusive interview last month.

Long before Bonaventura took that job, DCS was already facing scrutiny for its handling of several child abuse and neglect cases.

It still hasn’t been officially determined if the three children in the Hammond house fire died because of neglect. But, in the wake of that incident and others, some see a pattern of neglect from those who oversee DCS down in Indianapolis. They say the agency, with 34-hundred employees scattered throughout 92 counties, doesn’t get enough money or resources to properly do its job. And they point to other cases where kids may have fallen through the cracks as a result.

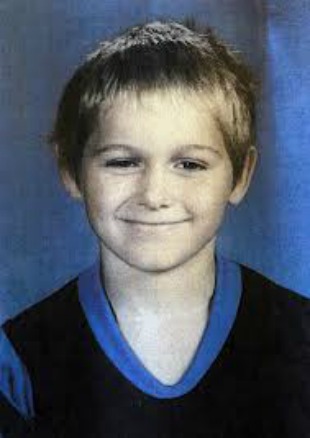

Like the notorious case of Christian Choate, a 13 year old Gary boy whose body was found buried under a concrete slab in a trailer park in 2011, two years after he was first reported missing.

Bonaventura holds Christian Choate’s father and stepmother responsible, and both are now serving time in prison. She also blames the parents of the three Hammond kids for allowing them to live in a house with no utilities.

Still, Bonaventura wonders if the agency she now helms, which handles 13,000 cases at any one time, could have done more.

“Can we ever prevent that from happening? We don’t know on a daily basis what people are doing in their own homes,” Bonaventura said. “But once we get involved with a family, we darn better should know what’s going on in that home and prevent any further injury to any children.”

For DCS to ‘know what’s going on in a home’ it requires money to hire, train and keep experienced case workers – who make up nearly half of Indiana DCS’s 3,400 employees.

The average pay of a DCS family case manager is $35,000 a year – this from a state with a $2 billion surplus.

“It doesn’t do us any good to have a surplus that’s built on the backs of Hoosiers, on the backs of the less fortunate. And these kids have nobody to speak for them but the state,” said Indiana State Rep. Mara Candelaria Reardon, a Democrat from Munster in Northwest Indiana.

The veteran Democratic lawmaker takes issue with DCS budget cuts under recent Republican administrations. But more than that, she says DCS has also been giving money back under a process called reversion.

$62 million in 2011 alone according to state records, nearly 14 percent of that year’s DCS budget.

In fact, in the last five years, the child protection agency has returned more than $118 million to state coffers.

Reardon says imagine all the DCS caseworkers you could hire with that money.

“The padding of the surplus that’s been touted nationwide, Indiana’s surplus,” Reardon said. “If we actually paid people more and had more employees to handle the workload, you might not have the turnover that you see.”

Two years ago, the turnover rate among DCS caseworkers was as high as 50 percent in some parts of the state. It can be a traumatic job, and state law stipulates that caseworkers are supposed to have no more than 12 active cases while monitoring 17 children.

![Indiana State Rep. Mara Candelaria Reardon [D-Munster] says Indiana’s DCS has returned millions of dollars back to the state in order to “pad” the state surplus. (Photo provided by the Statehouse File of Indiana)](https://s3.amazonaws.com/wbez-cdn/legacy/image/Indiana%20DCS%202%20%283%29%20.jpg)

According to DCS’s own report from last year, only 3 of its 19 regions were in compliance with the state-mandated caseload law. And more cases are coming in since Indiana recently centralized its child abuse hotline. Last year, case workers handled more than 150,000 calls of potential abuse.

“That doesn’t even include the children that we haven’t had contact with because a judgment call was made at the call center. These are actual real life children that need care and are in danger, and are not getting the services that they need,” Reardon said.

After all the grim news, DCS may be starting to turn things around. This year the state is allocating $13 million in additional money to hire more case workers, boost salaries and enhance its child abuse hotline.

Last week, a DCS oversight committee, the Commission to Improve the Status of Children in Indiana, reported employee turnover has fallen below 16 percent on average.

But, even with the changes, DCS will not comply with the 12/17 standard unless additional measures are taken. In order to further ensure that caseloads are in compliance with the 12/17 standard, DCS will need to create 110 new Family Case Manager positions, according to Indiana’s DCS 2013 annual report.

Alfreda Singleton-Smith is DCS’ ombudsman, an independent state watchdog for the agency.

“The issue of fatality reviews and near fatality reviews is the one that started to be of concern simply because of the length of time it was taking to get those completed,” Singleton-Smith told WBEZ.

Singleton-Smith recently issued a report that found it was taking up to two years in some cases to investigate the deaths or near deaths of children. In that same report, Singleton-Smith said the delay was about more than DCS.

“In some cases, DCS has to wait before they can complete their fatality review. The coroner, the prosecutor’s office, law enforcement, the hospital, those outside individuals who have their own processes that they have to go through,” Singleton-Smith said.

Still, DCS head Mary Beth Bonaventura says her agency can – and must – do better.

“Two years is not acceptable. I just think there is so much to do at this agency and maybe at some point, not enough people to do it.”