One day Matthew Owens, a civil rights attorney and part-time volunteer for the Jewish Council on Urban Affairs, was perusing the Chicago City Clerk’s website and he read something that he thought might be useful in his advocacy work.

“I came across language indicating that citizens could introduce legislation into City Council,” Matt told Curious City. But he couldn’t find any more information about how the process actually works. “And I am a bit of a like citizen engagement nerd, so I found the idea pretty interesting.”

Matt was doing research as part of his work with GAPA — the Grassroots Alliance for Police Accountability — a coalition of community groups in Chicago that spent two years drafting a police reform ordinance in the wake of the high-profile 2014 police killing of Laquan McDonald.

And he wondered: Could citizen legislation be an alternative way to push police reform through City Council? And even beyond police reform, could this be an effective way to get things done in Chicago?

Matt’s right. The power does exist — but it turns out there’s no clear set of rules for how a citizen is actually supposed to do it. The City Clerk’s Office describes it as a “rare occurrence,” while a former alderman characterized it as a “phantom right.”

But before we get into that, you may need a primer on how things are usually done at City Hall.

Here’s how an ordinance is normally passed

For those who don’t follow the daily minutia of city government, the normal process of passing an ordinance goes like this. (As a reminder, an ordinance is a proposal to change a local law. It is often used interchangeably with the word “legislation.”)

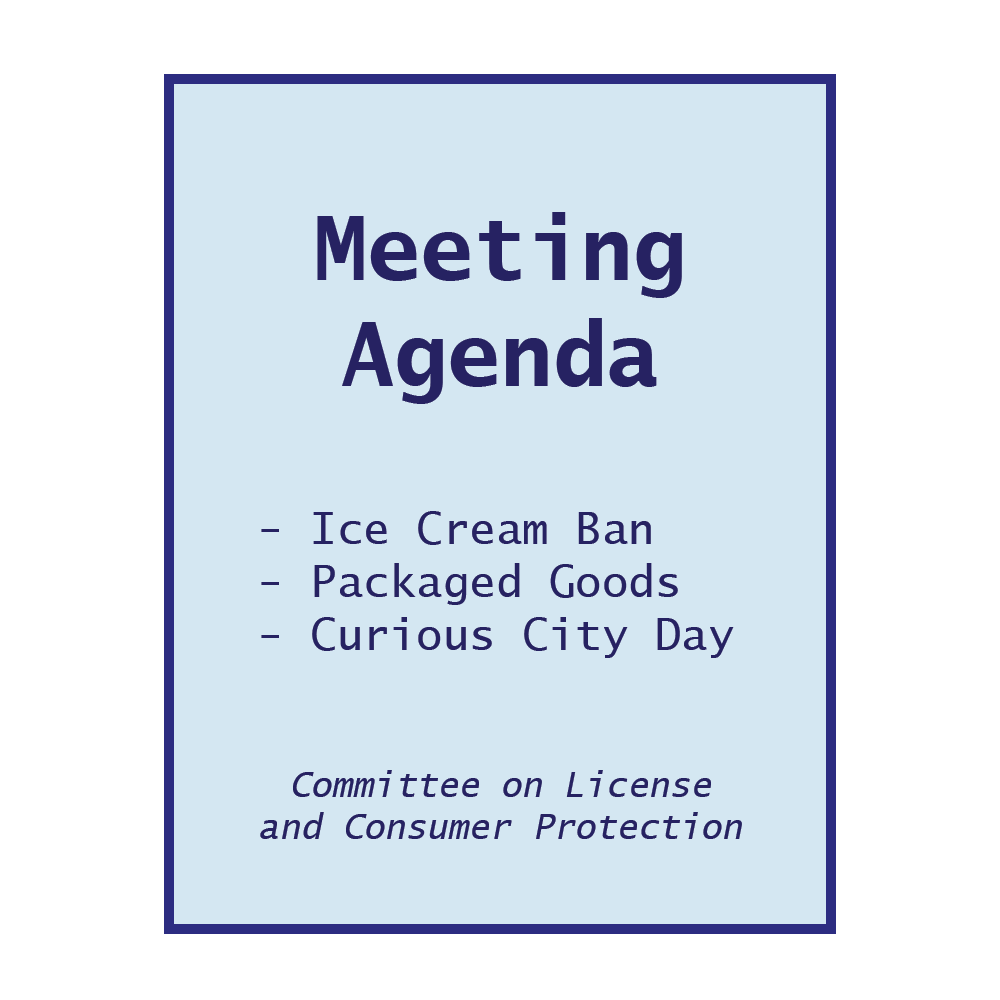

STEP 1: An alderman, city commissioner, department head or the mayor submits an ordinance to the City Clerk’s Office.

STEP 2: At the monthly City Council meeting, the City Clerk reads the ordinance and assigns it to one of 19 City Council committees.

STEP 3: The Chair of the Committee decides whether to discuss the ordinance in a committee meeting.

STEP 4: If the Chair decides to discuss the ordinance, aldermen on the committee hear expert testimony — as well as comments from the public — before they vote on the ordinance or table the vote for another meeting. (On rare occasions, a proposal could die in committee. But that’s another story for another day...)

STEP 5: If the ordinance passes the committee by a majority present, it heads to the full City Council for a second vote. Once approved by a majority of City Council, it becomes part of the Municipal Code, a local law.

Throughout this process there are a myriad of potential roadblocks, including fancy procedural moves aldermen can take to block items from even getting a vote and powerful committee chairmen who can choose to shelve an item never to be heard from again.

It’s a delicate dance of strategy and opportunity that makes it hard for a lone alderman to sponsor citywide legislation — let alone a regular citizen, according to current and former staff members of the City Clerk’s Office who spoke to Curious City about Matt’s question.

For citizen-introduced legislation, ‘There’s not really a concrete procedure’

With help from former Rogers Park Ald. Joe Moore, Curious City found the single sentence on the Clerk’s website that spells out this rule: “Legislation may be introduced by the Mayor or the executive departments, by one or more aldermen, by a City Council committee, or by a citizen (through the City Clerk’s Office).”

There are no instructions on the website to explain how citizens can do it.

The gist: Yes, people have the right to file an ordinance with the City Clerk. But once it is formally submitted to the City Council, the person who submitted the ordinance has no mechanism to steer it.

“It’s just not a very, it’s not a common occurrence [for citizens to submit an ordinance]. Because it’s just beneficial for a community organization or a resident to work with their alderman directly,” Treshonna Nolan, the spokesperson for the City Clerk said.

Which makes sense, right? If you want to push something through City Council, it helps to have an alderman in your corner.

But Nolan said citizen-led legislation isn’t just uncommon; “there’s not really a concrete procedure,” she said, adding that there isn’t a roadmap — or any written rules — for how citizens can do it.

It’s not in the Municipal Code, the official book of local laws, or the Rules of Procedure, the rule book for how city council is governed.

Former City Clerk staffers who have since left the office but asked to speak on background because they are still in positions of government told Curious City that this is a particularly sensitive topic. And it’s not more broadly known because there’s a concern that it could open the floodgates to dozens of citizen-led introductions.

If there’s no formal procedure, has anyone been able to do it?

Dozens of citizens have submitted legislation to City Council in recent years, but they’ve often faced obstacles in the process and ultimately none of these proposals were passed into law.

About 30 years ago, before he was an alderman, Joe Moore said he tried to use this process to get the city council to hold a hearing on community policing. But he recalls, “Nothing ever came of it. They never called my matter up for a hearing to my recollection.”

Looking back on it, Moore said he’s not surprised his proposal never went anywhere. As a former committee chairman, he knows all about the discretion they have in deciding what moves through City Council.

He says unlike aldermen — who have the power to release an ordinance that’s been languishing in committee after a certain time has passed — average citizens don’t have that power. And that ability to discharge legislation from the hands of an uncooperative committee chair rarely happens because it's a politically savvy move that requires majority support— meaning at least 26 aldermen would have to vote in support of pulling the ordinance out of the committee where it has been languishing.

“[A citizen] would have to convince an alderman to make that motion [on the floor of the city council],” Moore explained. “So it's a right (to introduce legislation) that citizens have, but it's probably more of a phantom right than an actual right.”

And, he adds, the only reason he knew about it before he became an alderman is because he was a city employee at the time, working in the Law Department. “I had an inside track, if you will.”

But having an inside track is no guarantee that any action will happen. A sixth grade class from Ray Elementary School in Hyde Park tested out the citizen process with the help of former Illinois governor Pat Quinn.

Quinn accompanied the students to the City Clerk’s office where they submitted an ordinance banning restaurants and street carts from serving food in single-use styrofoam containers. The ban would apply to on premises and to go orders. In their accompanying letter, the students cited recent bans that have been adopted in other cities, as well as a contact for their “assistant” — the former governor.

“The students handed in their ordinance, which was referred to the environmental committee, headed by Alderman [George] Cardenas,” Quinn said. But the committee has never called the kids to testify. And their ordinance, while still active, has just been sitting in committee purgatory.

“So it's a little disappointing,” Quinn said.

Other citizens have introduced ordinances to increase taxi fares, impose term limits on aldermen, impose stricter regulations on recycling and waste management, and change the way police officers and meter maids issue parking tickets. Several citizen groups have submitted proposals for how the city should redraw its ward map — a process that happens every ten years after the census — and one sign company tried to introduce their own digital sign permits at several sites across the city. According to Legistar — the website where the city clerk lists all city council meetings and the items they will be voting on — none of these proposed ordinances have passed. They either died when a new council was sworn in or have just stalled in committee like the styrofoam ban.

Quinn believes the process can improve

Quinn thinks the way citizens introduce legislation could be reformed to give them a seat at the table. Aldermen have parliamentary maneuvers they can rely on to work around unhelpful committee chairs, as Moore mentioned, but citizens do not. Quinn said that should change.

One suggestion he had is a signature requirement that could force council action. If a citizen can show that there’s real support behind their proposal with 5,000 to 10,000 signatures gathered — similar to that of a petition process — then the council should be required to at least hold a hearing on it.

“The idea that democracy is sort of a closely held process by insiders, that's not so healthy,” Quinn said. “You should always have a safety valve where if the insiders are not paying attention to something, then the voters have a way to go.”

Quinn also believes there ought to be a requirement that citizen ordinances get a vote in City Council.

“Unfortunately, there's no requirement that the council itself take a roll call vote on the citizen ordinance. And I think that's a real shortcoming,” Quinn said.

But it would take aldermanic approval to make these kinds of changes

And while Matt Owens, our questioner, was disappointed to learn that the process hasn’t been very effective, he still thinks it’s a good thing this citizen power exists.

“I still think it’s a nice idea, this symbol of what city government could be,” he said.

Claudia Morell is a city politics and metro reporter for WBEZ.