When you ask the students at Leo Catholic High School in Chicago’s Auburn Gresham neighborhood what they like most about Black History Month, they’re eager to answer.

“Every year during Black History Month, I find out something new that I never knew,” one student said.

“I like the culture and how it brings everybody together,” another added.

In Chicago and across the country, it’s become an expectation, especially in schools to celebrate Black History Month in February. In more recent years, Chicago’s role in creating the commemorative month has become more widely recognized.

The celebration’s start

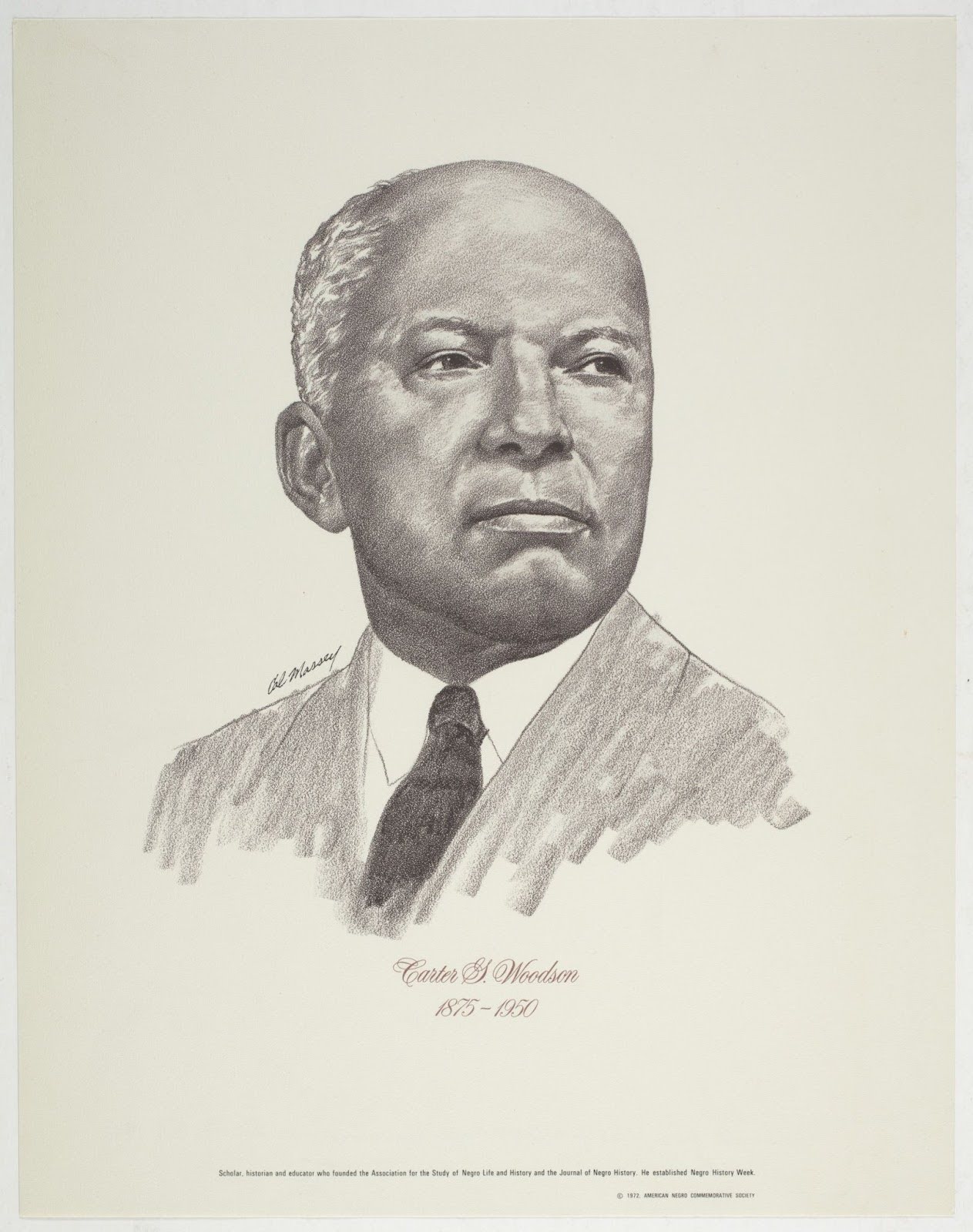

In 1915, scholar and historian Carter G. Woodson traveled from Washington, D.C. to Chicago for the National Half Century Exposition and Lincoln Jubilee — a celebration of 50 years since emancipation and Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. The event was held in the Chicago Coliseum. Woodson was both an attendee and a presenter and was inspired to do even more for Black history.

He was the son of former enslaved people and overcame obstacles to gain his education. He earned a master’s degree from the University of Chicago and became the second Black American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. He was passionate about education.

After the Jubilee, Woodson returned to the Wabash YMCA in Bronzeville where he was staying. Black men visiting the city could book rooms at the Y’s hotel, including men moving up from southern states during the Great Migration before bringing up their families.

From the 1910s through the ’60s, the Wabash Y was an essential social center for the Black community. With its gym, swimming pool, cafeteria, and grand ballroom, it was home to sports teams, cotillions, social justice meetings and other events that brought Black people in the city together.

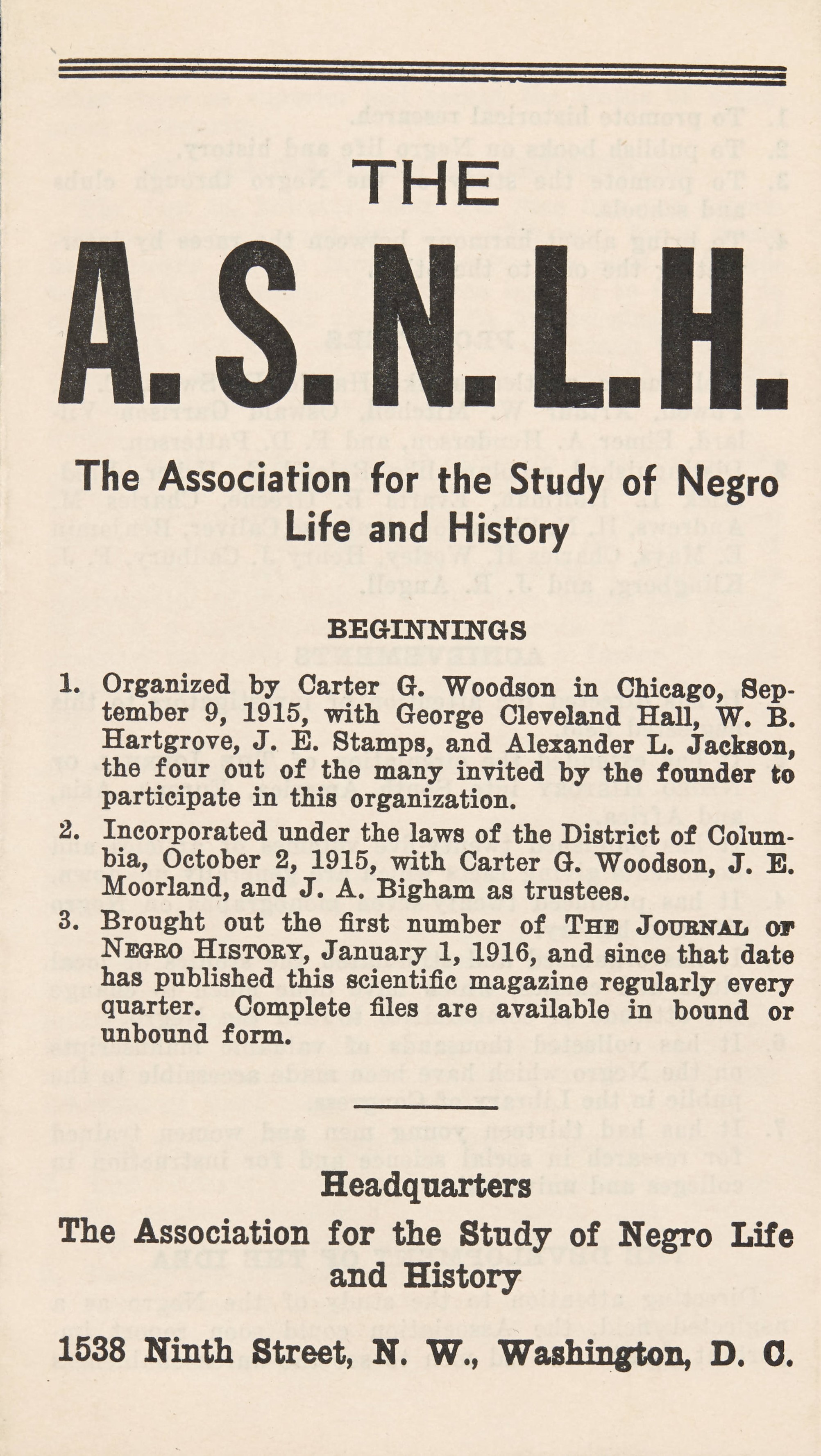

During Woodson’s stay, he got the idea to formally create the Association for the Study of Negro Life in History, which later became the Association for the Study of African American Life in History. The first way the organization shared Black achievement was by publishing a journal in 1916, The Journal of Negro History.

“Woodson did not establish this association … solely to create a scholarly journal, but he was motivated by wanting to create a public presence for Black history,” said Daryl Michael Scott, a history professor at Morgan State University and former national president of the ASALH.

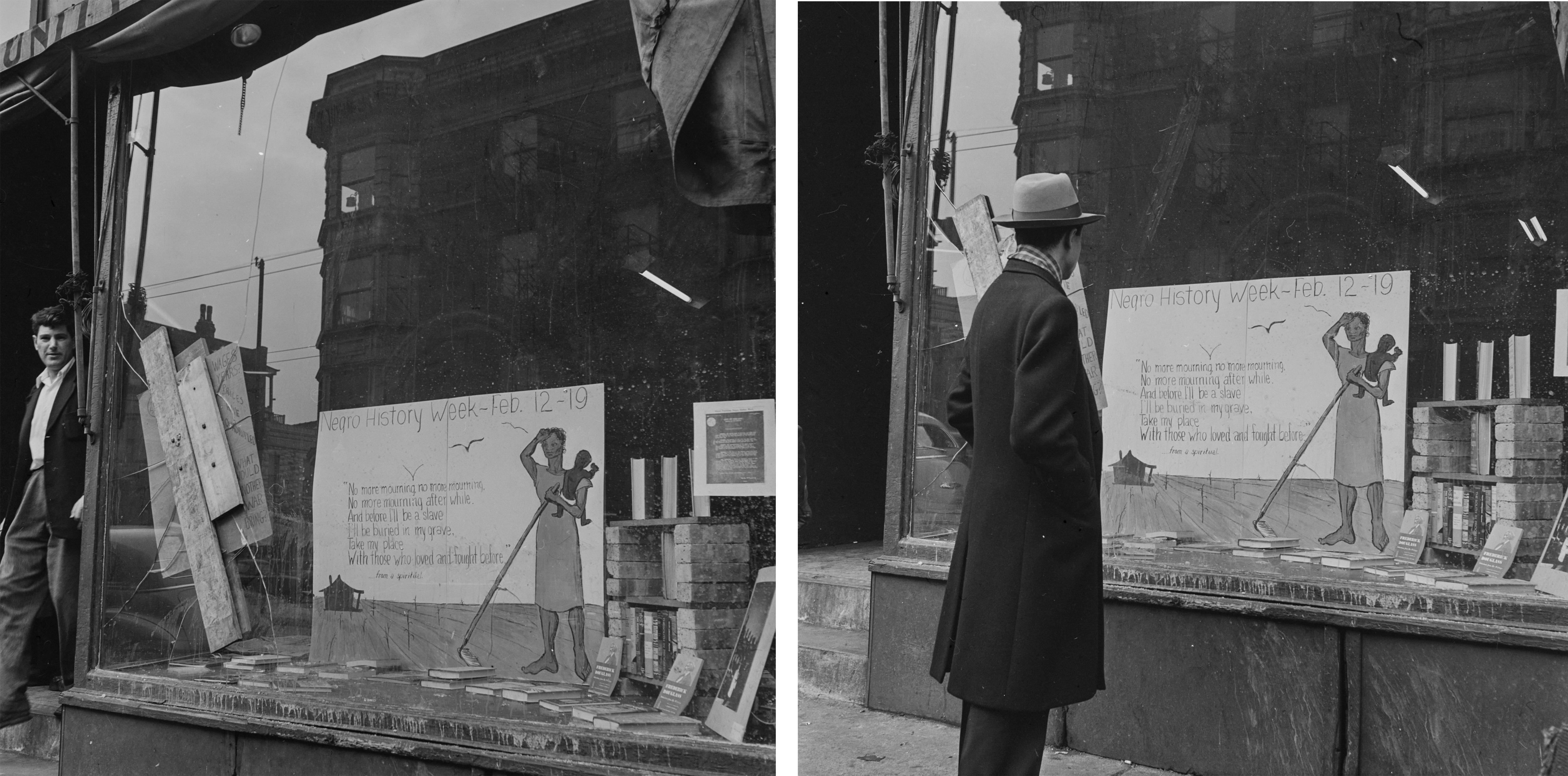

In 1926, the ASALH launched the first Negro History Week. Woodson selected a week in February that included Frederick Douglass’s birthday on the 14th and Lincoln's birthday on the 12th. People already celebrated those days, and his goal was to build on tradition.

Scott said Woodson folded this week into pre-existing celebrations to show Black people they were a part of something greater. Then, he said, this American story becomes much larger than the individual — bigger than Douglass and bigger than Lincoln.

“This story becomes a story in which Black people can see that they're a part of a big canvas of human history,” Scott said. “So the themes would be not the achievements of Frederick Douglass or the achievements of Sojourner Truth or anyone else. It's about the role of Black people in bringing democracy to America.”

Growth and expansion

During the late 1920s and early ’30s, Negro History Week grew in popularity, with Black communities across the country taking part.

However, Negro History Week faced some resistance at the time. Woodson wrote an article for the Chicago Defender in 1932 defending its merits. Among a number of incidents, Woodson wrote that an educator was hesitant about celebrating in school because he did not want to disturb the “peaceful interracial relations” with white people in that community. Woodson wrote of another example of a white school superintendent who questioned the intentions behind Negro History Week, whether Woodson was “safe” and could “teach his people to stay in their place.”

Woodson countered that the naysayers were “victims of propagandists,” and were not keeping up with the times. He said many school districts in the North and South were commemorating the week. He pointed to a teacher in Washington, D.C., who said discipline became less of an issue because students were inspired by the lessons and became “ambitious to make the most of themselves.”

The week also became popular with progressive white people who were celebrating National Brotherhood Week, which was also celebrated in February. It was created in 1927, shortly after Negro History Week launched, to fight against anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, and anti-Jewish hate — sentiments that stemmed from World War I. In some cases, the two weeks were even combined.

“A lot of the people who celebrated Brotherhood Week start celebrating Negro History Week as a way of furthering that same goal of creating one society,” Scott said. “So [in] the 1920s … you get these movements that are trying to heal wounds.”

The ASALH asked for donations to help create materials including books and radio broadcasts. They helped newspapers develop special pages highlighting notable Black people of the time. The idea was for readers to cut the page out as a keepsake.

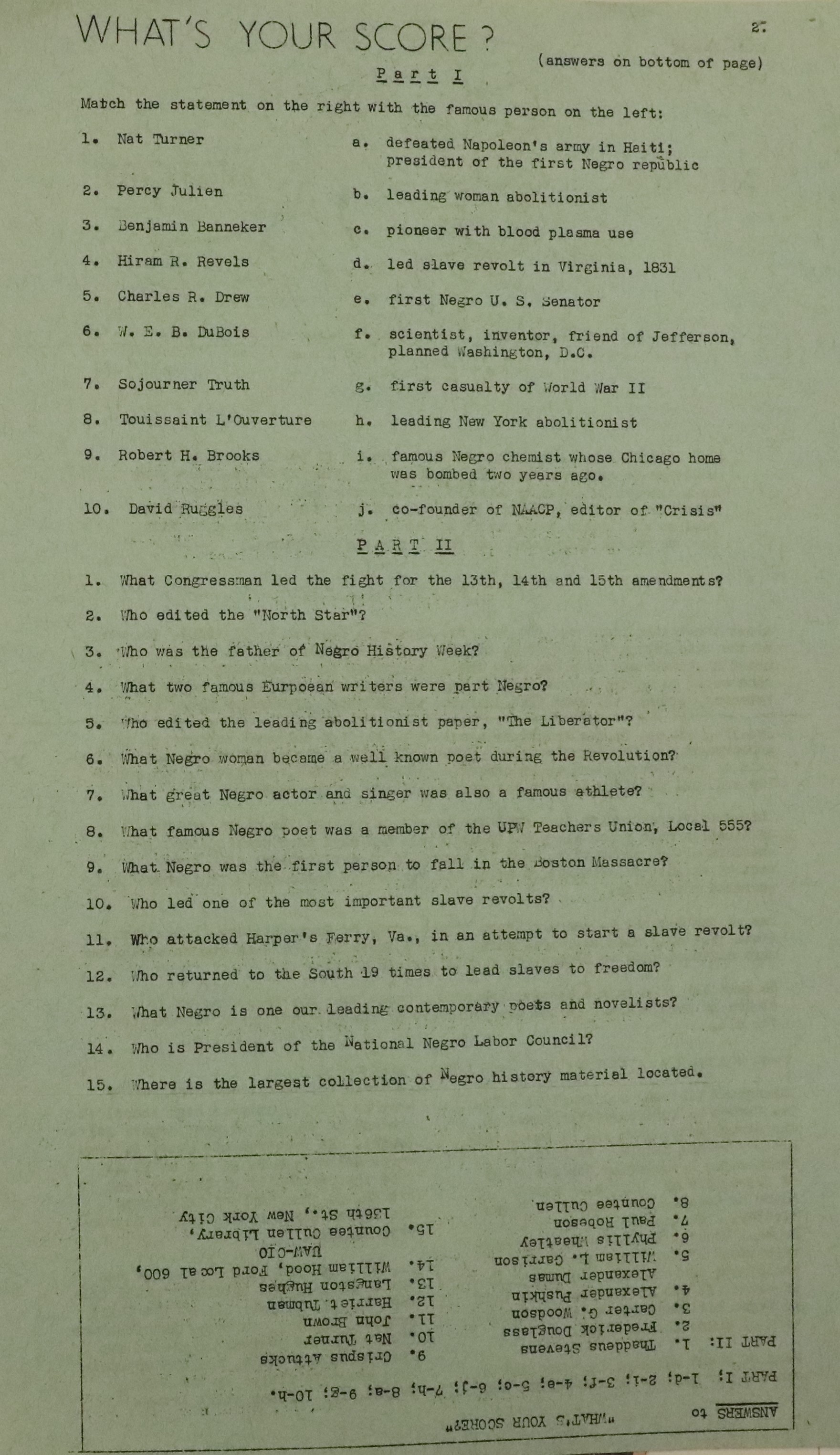

To help teachers, the organization delivered lesson plans, posters and even playscripts to incorporate into their curricula. Students could also test their knowledge with a quiz tailored for the week, including questions like “What two famous European writers were part Negro” and “Who edited the ‘North Star’?” Woodson’s goal for Black history was set in motion.

“[Woodson] really believed that if the truth about Black people and their history was told to Black people and the public, it would transform how Black people saw themselves, how other people saw Black people, and how Black people would fit into American democracy and how Black people would fit into world history,” Scott said.

Negro History Week becomes Black History Month

Negro History Week continued to grow and expand in the second half of the 20th century.

Its organizers also made changes, often in response to feedback from young members: The ASALH moved from using “Negro” to “Black,” added links to Africa as part of the Black American past and, in 1976, extended the week to Black History Month.

“Chicago at the time, and Chicago today, continues to be that beacon, a hub, an important city,” she said. “This has always been the case for Chicago.”

For example, Jean Baptiste DuSable as the first non-Native Chicagoan or the trailblazing work of journalist Ida B. Wells are just a couple of pieces of Chicago’s history.

Much of the archives of what happened in Chicago is also housed here. That’s thanks to Vivian Harsh, Chicago Public Library’s first Black branch head. She was an active member of the ASALH and created the Special Negro Collection which was a collection of African American history and literature at the George Cleveland Hall Branch in the city’s Bronzeville neighborhood. Among the first donations to the collection were about 200 books from the private library of Dr. Charles Bentley, a dentist and leader of the local NAACP. Today, it’s the largest collection of its kind in the Midwest and is now housed at the Carter G. Woodson Regional Library in the Washington Heights neighborhood.

“Vivian Harsh was also collecting images, materials, documents that all spoke about — and for — Black lives in Chicago and beyond,” Griffin-Fabicon said.

At the Hall Branch, famous Black Americans like Gwendolyn Brooks and Langston Hughes would gather, but it was also a place for the public. According to the Chicago Public Library, as more Black history clubs were created, teaching materials became high in demand. Harsh made those resources easily available, and she organized many Negro History Week programs at the library before she retired in 1958.

Griffin-Fabicon said Woodson hoped Black history would eventually be better integrated into American history as a whole.

“[Woodson] felt that … if we simply make those stories part of our curriculum, a part of our narrative, then we would not have to have this particular time where we're amplifying Black people within this month, it would be history writ large, 365 days of the year,” she said.

But, Black history is not completely recognized across the country in the way Woodson envisioned. Some state governments continue to debate the value of Black history curriculum. In the past few years, legislation has been introduced in several state legislatures to restrict education on racism and contributions of specific racial groups to U.S. history. Such legislation has been successful in states like Tennessee, Florida and Texas.

In Illinois, lawmakers have considered a bill that would require schools to post learning materials for parental review and another that would give parents the power to oppose material they find objectionable.

Arionne Nettles is a university lecturer, culture reporter, and audio aficionado. She is the author of We Are the Culture: Black Chicago’s Influence on Everything. Follow her @arionnenettles.