An Arabic-language summer camp connects children of refugees to ‘the memory of the country’

The Edgewater camp grew out of conversations with parents who worried their children could not read or write their home language.

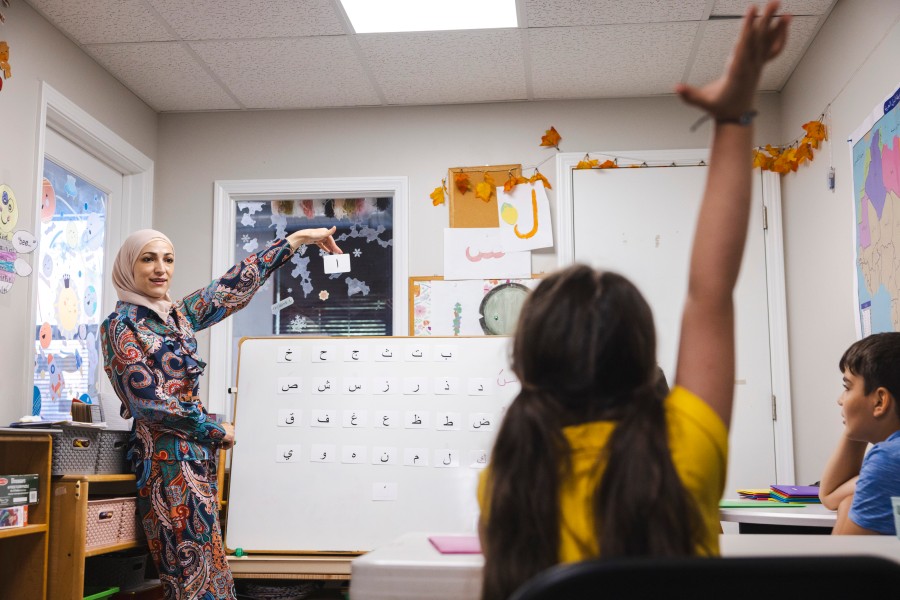

By Elly FishmanIt’s a little past 10 a.m. and Samira Alhamwi leads a group of nine elementary school-aged children in a jazzy version of the Arabic answer to the “ABC Song.”

It’s the second week of Arabic camp at the Syrian Community Network, an Edgewater nonprofit, and the students’ enthusiasm ricochets off the walls as though they’re singing a Taylor Swift hit, or better yet, one by the Lebanese pop sensation Nancy Ajram, rather than an educational rhyme.

Alhamwi, a Syrian refugee herself, starts every morning with the upbeat tune. It’s an essential pillar in the Arabic curriculum that she designed and is now teaching over a new, five-week camp this summer.

“This camp is really the result of conversations with our parents,” said Nate Sivak, the education director at the network, which helps refugees and immigrants navigate resettlement and all the hurdles coupled with building a life in a new country. “Syrian refugees who arrived five to seven years ago now have children who do not read or write in Arabic. We heard from a lot of families who feel their children face a disconnect and identity crisis between two worlds.”

Arabic is the official language in 22 countries around the globe, and in Chicago, around 13,000 people primarily speak Arabic at home. Across the city, it is, after English, the fifth most spoken language at home after Spanish, Chinese, Polish and Tagalog.

But it’s not always easy for native speakers to figure out how, in a city like Chicago, to preserve the language of their homeland. Outside of mosques and religious groups, there are few options, particularly for young people. For parents raising their families here, teaching their children to speak Arabic is not only a critical part of identity, but also an important way to remain connected to literature, current events and family who remain in countries far away.

The Edgewater camp also offers a solution to an annual summertime dilemma for Chicago families: How to keep kids busy and engaged without breaking the bank. “We wanted to make an organized effort to teach Arabic literacy,” said Sivak, “and we wanted to create something new and fun.”

When the rousing rendition of the alphabet song finishes, Alhamwi turns her attention to the board beside her. She holds up a small laminated card that features a single Arabic letter.

“Today our new letter is the letter, Nün,” she says to the class. “What is its name?”

“Nün,” the children respond in unison.

“Nün. N-Ü-N. What sound does it make?”

“Nnnn,” they say.

“Nün” is the third of 29 letters that Alhamwi hopes to teach the students over the course of the class. The goal is to introduce them to Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), which in Arabic is called “al-Arabiah al-FusHa,” and translates to “Refined Arabic.” It is the formal language shared across the Arab world. Modern Standard Arabic, which is based on Quranic Arabic, is used in books, academia, law, and media, but rarely spoken in casual conversation.

The first activity is drawing the letter on construction paper. Each student takes out a box of crayons and markers and begins to trace the “u”-like shape. Alhamwi, and her assistant teacher, who came to Chicago from Iraq in 2022, circle the small room. Next, she instructs the students to make paper bumble bees, or nahla in Arabic.

At one table, Tala, who is 8, begins cutting her paper into three circles.

“Buzz, buzz,” Tala says, elongating the “zee” sound as she waves the black and yellow circles in the air. As Tala works, the nahla turns into an oreo cookie, an ice cream taco, a decorative hat, and, later, a relaxation button.

Tala, whose buoyant energy complements her bright yellow sundress, was born in Jordan and speaks Arabic at home. But much to her parents’ concern, she only reads and writes in English.

“My grandma doesn’t let me speak English,” Tala says, gluing googly eyes onto her bee.

“My mom doesn’t like it when I speak English,” adds Adam, a Syrian 6-year-old who sits beside her. Both Tala and Adam attend nearby public elementary schools where classrooms include a mix of American-born kids and refugee families from all over the globe. “But I like it.”

“Yeah, me too,” Tala agrees.

Behind them, Sidra, a Syrian 11-year-old, studiously builds her bumble bee. Sidra arrived in Chicago with her mother just a couple months ago after six years in Turkey. The move reunited Sidra with her father, Mohammad Zaazaa, who was resettled in the U.S. in 2016. Like many young refugees, Sidra’s education was interrupted during her years in Turkey, where the promise of resettlement in the United States kept the girl and her mother in limbo.

Sidra, who responds in clipped, hushed answers, says she’s excited to make friends and learn written Arabic. Her father is equally enthusiastic.

“I stopped school when I was 9-years-old in order to work for my family,” shared Zaazaa, 38, who grew up making textiles in a factory before joining the Syrian army. An injury put him in a wheelchair. “For Sidra to learn the mother tongue the way it should be learned is really a dream for me. It’s how she will carry the memory of the country.”

Creating a positive connection to the more formal written language sits at the heart of Alhamwi’s lessons, too. “When I came to the United States, I knew I had to teach my children [to read and write] Arabic,” said Alhamwi who has two young daughters. “And I don’t like the classic way. It’s not very interactive and a lot of kids have bad experiences that make them hate the language, unfortunately.”

That’s why Alhamwi committed to building each language lesson from scratch. In the end, it took her six years to create the unique curriculum, which uses memory games, songs, picture books, art projects and videos. Though Alhamwi tailored the lessons to her two daughters, she always imagined adapting it for a classroom setting. “It was my dream,” she says.

Back in the long, narrow classroom, the paper bumble bees dry on a bookshelf and Alhamwi once again stands at the front of the room. She opens the book The Missing Sheep toward her attentive young audience.

As she reads, Alhamwi first articulates the formal phrases written in MSA— “One day Grandfather got sick”— and then translates them into a Syrian dialect — “This grandpa got sick”— so the students connect the two versions of the language. “I want them to see the connections and not get bored,” said Alhamwi. “But it means we go through the book much more slowly.”

The morning lesson finishes with the Syrian song “The Light of My Eyes, My Country, My Heartbeat,” an anthem that celebrates, and longs for, Syria’s natural beauty. When the song ends, Alhamwi releases the students for lunch. The meal, like everything at the camp, is free. Sivak estimates that the camp, which serves nearly 45 kids across three classes and age groups, costs around $20,000 to run. Most of that funding comes from an afterschool grant from the Illinois State Board of Education, which funds some enrichment programs run by independent organizations.

As Alhamwi cleans up the room, her elder daughter, Maria, slides into a chair. She comes to camp with her sister, but neither attends the morning lessons. They don’t need to.

“I still remember the first time Maria read in Arabic,” says Alhamwi looking at her 11-year-old. “I started crying. I was so proud of her and I was also proud of myself because it took me a very long time to reach that moment.”

For Alhamwi, teaching her daughter to read Arabic was not only an exercise in literacy, but cultural exploration and preservation. “Language is our identity,” says Alhamwi. “It’s our culture. It’s what connects us to our homeland.”

Elly Fishman is a freelance writer and the author of “Refugee High: Coming of Age in America.”

CORRECTION: Samira Alhamwi’s teaching assistant came to Chicago from Iraq in 2022, not 2014.