Fertility Clinics Shut Down During The Pandemic. Now, New Patients Are Rushing In.

By Araceli Gómez-Aldana

Fertility Clinics Shut Down During The Pandemic. Now, New Patients Are Rushing In.

By Araceli Gómez-AldanaIn March 2020, during the early days of the pandemic, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine sent out guidance to all clinics and hospitals pausing fertility treatments indefinitely.

Fertility clinics weren’t considered essential, meaning their services were shut down for months. The only women who could receive treatments were those with cancer.

The cutoff in infertility treatments dealt the largest blow to patients who were looking forward to beginning their fertility journey, especially for those whose age was a factor in their treatment. Time was of the essence, because, in their situation, it could be now or never. And access to the costly, time-consuming treatments had evaporated.

Dr. Kara Goldman is an infertility specialist and the medical director of fertility preservation at Northwestern Memorial Hospital.

Goldman worried about her patients’ mental health during the pandemic.

“To have that rug pulled out from under them — not only do they need to rely on assisted reproduction, but now they can’t because we can’t offer that care is absolutely devastating,” said Goldman. “There were a lot of really hard conversations, and I think the hardest part in those early days was not knowing how long it would last.”

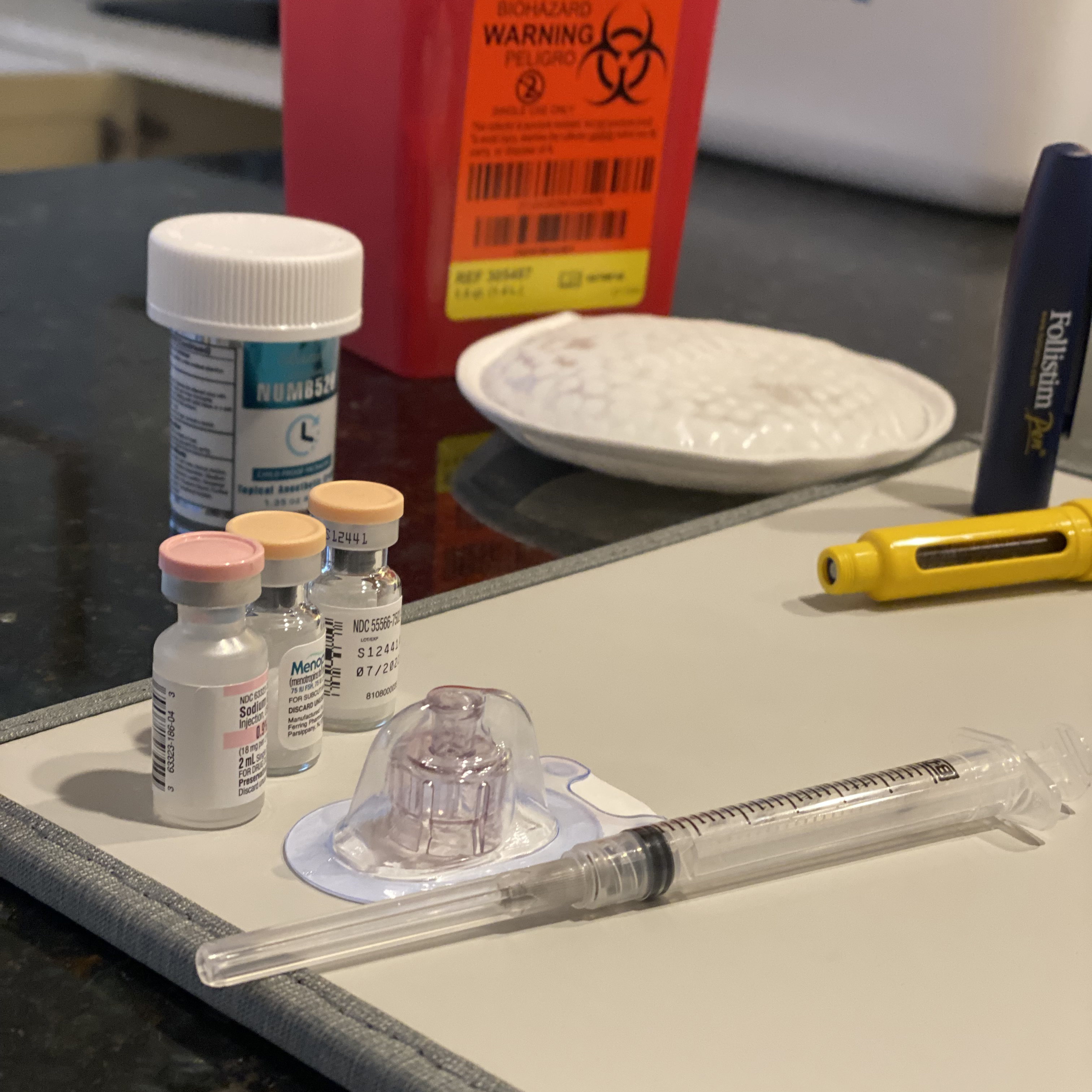

Infertility is a medical disease. Treatments range from intrauterine insemination (IUI) and in vitro fertilization (IVF), to fertility preservation like embryo or egg freezing.

About 10% of women will need medical treatments to get pregnant in the United States. That’s more than 6 million women.

Treatment also comes with a hefty price tag.

According to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, the average cost of an IVF treatment in the U.S. is more than $12,000. Many patients require several rounds of treatment before achieving a pregnancy.

Some state laws, including Illinois, require medical insurance to cover the costs, diagnosis and treatment of infertility.

Goldman questioned why fertility treatment wasn’t deemed essential during the pandemic, given the number of women it affects.

“I think that there’s always this misconception that infertility somehow is a luxury, like to be treated for infertility is a luxury,” said Goldman. “Infertility is a disease. It does not discriminate. Infertility care is essential. And it’s never elective.”

Now, fertility clinics have reopened and are experiencing a rush of patients. Demand is high, leaving doctors to treat old patients and long lists of new ones.

Goldman said there are a few reasons why patients made the decision to seek fertility treatments post lockdowns. Perhaps people weren’t dating during the pandemic, which altered their perceived timeline to have a baby.

Time and access may have played a role as well. People had fewer distractions and more time during the pandemic. There was less traveling for work. Some may have the ability to work from home, making the extensive process of fertility treatments more accessible.

But Goldman said her patients often tell her the pandemic forced them to stop and think about their future and family planning.

That was the case for Kristen Field.

Field lives in Chicago and runs Friends of Prentice, a nonprofit focusing on women’s health. Field said before the pandemic she was OK with postponing the conversation about family planning.

“I started this journey, I was newly 36, starting this new job, [and] I thought ‘sky’s the limit,’ ” said Field. “But there was something that made me really think about the idea of a partner and the idea of having a family, and that they didn’t necessarily have to be fully exclusive together.”

Field began her fertility preservation treatment with Goldman in January, when appointments began to open up. The process took about six months, and she paid about $12,000 out of pocket.

She documented her fertility preservation journey publicly on social media.

What surprised Field the most was how much she learned about her body and women’s reproductive health in general, things she said you don’t learn about in high school.

“I wish, when we were younger, that it just was talked about this way. But it’s not part of your overall holistic health care. I want to know about how my body works,” said Field. “In this whole experience I wanted other women to know those things to be empowered around their own health, whatever decisions they make.”

Field said the lack of awareness around fertility treatments was one of the reasons she documented and publicly shared what she went through.

By sharing her own story and putting herself out there, she was hoping that would make others feel safe to also share.

“What I realized in sharing and just providing a little bit of vulnerability, is it gives permission for others to feel safe to do the same,” said Field. “I just commend all the women warriors who have shared their personal stories with me, because I know it just opens up all of us to be more open about women’s health.”

Araceli Gómez-Aldana is a reporter and host at WBEZ. Follow her @Araceli1010.