Guardian Or Warrior? David Brown’s First Year As Chicago’s Top Cop Pulled Him In Two Directions

By Chip Mitchell, Patrick SmithWhen Chicago Police Superintendent David Brown stepped up to the microphone at a Monday morning press conference last June, it was to make a confession.

The city had just been rocked by a weekend of massive protests in reaction to the videotaped killing of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white Minneapolis police officer. And Brown’s department had spectacularly failed to handle the angry protests and protect businesses and residents from the city’s worst looting and gun violence in decades.

Brown spoke of a young woman at one of the protests who called on cops to say Floyd’s name. The superintendent admitted he was ashamed by his own response: He said he only “whispered” Floyd’s name even though what he had seen on TV convinced him a police officer had committed murder.

“Today, publicly, I want to say his name,” Brown told the reporters. “As a police leader of the second largest police department: Mr. George Floyd, we grieve with you and your family. We are embarrassed by the cops in Minneapolis.”

At that moment Brown crossed the so-called blue line to express solidarity with protesters.

This was the reform-minded leader that Dallas residents came to know during Brown’s six years running that city’s police department. It was the leader that Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot promised when Brown took his oath as the top cop here one year ago.

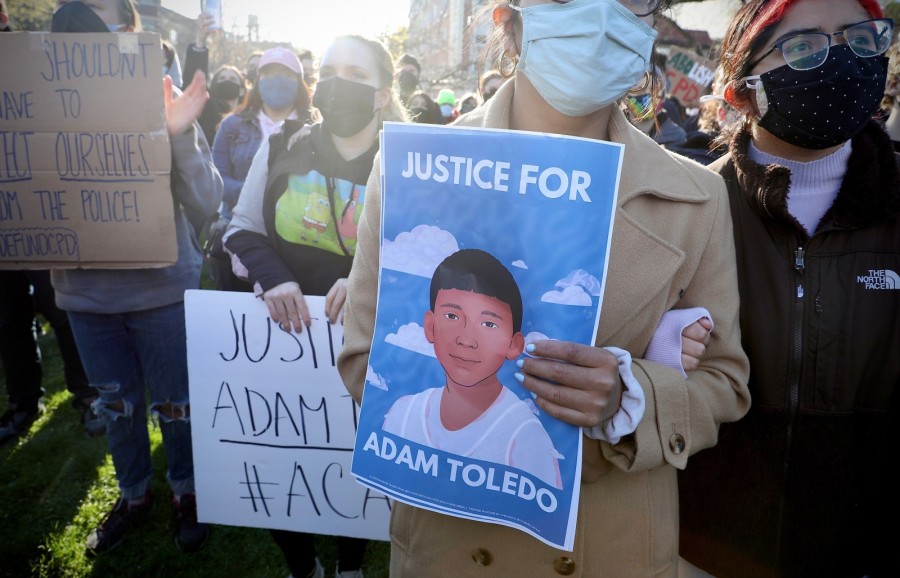

But the internal conflict Brown experienced when a protester told officers to say Floyd’s name mirrors the conflict he’s had as a leader in a city demanding solutions. Murders and carjackings are way up. Trust in the police, way down. And now 13-year-old Adam Toledo’s killing by police has thrust Chicago back into the national spotlight.

Brown has pushed the department to uproot its historic code of silence and embraced community policing. But he has also faced intense public pressure to tamp down the violence and protect businesses from looting — problems built on decades of widening economic and racial disparities made worse by the pandemic.

Under that pressure, Brown has repeatedly turned to old-school police tactics: Hotspot policing by roving citywide units. Mass arrests of protesters. Full-throated defenses of cops recorded on video clashing with protesters. Calls to lock up more young men.

“In Dallas, he was trying the guardian style of policing,” Chicago-based police-reform expert Carlton T. Mayers II said, referring to an approach in which cops show empathy and work as members of the community where they are assigned. “In Chicago, he’s leaning into a warrior style.”

Brown the guardian

After retiring from the Dallas department in 2016, Brown published a well-received book, Called to Rise, chronicling his evolution “from a ‘throw ’em in jail and let God sort ’em out’ beat cop into a passionate advocate for community-oriented law enforcement.” His author bio describes Brown, 60, as “America’s chief.”

When Lightfoot announced Brown as her pick, she described him as a “tested and ready” police leader who would help reform CPD and improve the relationship between police and communities.

Brown earned praise in Dallas for taking a conciliatory tone with anti-police protesters while still supporting the officers who worked for him. Mental health advocates in Dallas and Chicago praised Brown’s selection because of his reputation as a leader in how police respond to calls involving mental health crises. His dedication to that issue was forged by personal tragedy: Brown’s son was killed in a shootout with police during an apparent mental health crisis of his own.

In his memoir, Brown said his son’s death changed him permanently as a police leader.

“Before I lost my son, I thought I really cared about other people’s troubles,” Brown wrote. “On one level, I did, but not deep down. Issues of mental illness, gun violence and drug use had never hit home for me until they hit my home, my family, my son.”

Taken together, a clear picture emerged of Chicago’s new top cop: a compassionate, thoughtful leader dedicated to repairing the city’s most beleaguered neighborhoods who would not tolerate officer misconduct.

At his City Council confirmation hearing, where aldermen had the chance to grill the potential leader of a $1.7-billion-per-year city agency, the tone was mostly positive and supportive of Brown, with many aldermen thanking him for agreeing to take on the role. By then, it was April 20, 2020, and it was clear that COVID-19 was going to have severe impacts on police functions.

Wesley G. Skogan, a Northwestern University political scientist who studies crime and policing, said those impacts included new obstacles to community involvement in policing — to “the kind of face-to-face stuff that the public really wanted to be involved with.”

Still, Skogan said, Brown pressed forward.

The department last summer expanded the Neighborhood Policing Initiative to four patrol districts after a pilot effort in one district the year before. The initiative, modeled after a New York City program, reserves more time for cops in geographic patrol beats to build relationships with neighborhood residents to address ongoing problems instead of just responding to 911 calls.

Brown also resumed community-consultation meetings in all 22 districts, said Skogan, who helps evaluate CPD community-policing efforts stemming from public outrage about Black teenager Laquan McDonald’s 2014 fatal shooting by a white officer.

When the department moved those sessions to Zoom last year, they set attendance records and brought in more young people and African Americans, Skogan said. And the department has started a program in which officers learn about the neighborhoods they patrol from trainers who are community residents.

“Under the hood, there’s been lots of activity on the community policing front, trying to adjust to COVID and trying to get ready for the post-COVID times that we’re all hoping for,” Skogan said.

Those community-policing efforts jibe with Brown’s commitment to reforming the department in accordance with a court-ordered plan known as the consent decree. Since taking over, Brown has beefed up staffing related to reform, and the department has upped its productivity when it comes to creating or reforming policies. He has also started holding regular meetings in which department bosses are called to the carpet if they are failing to hit consent decree obligations.

The latest report from the court-appointed expert who is monitoring the consent decree progress found the department is still missing most of its reform deadlines. But that report, which essentially covers Brown’s first eight months in office, is also the first time the monitor has expressed optimism that Chicago is getting on the right track.

Brown has also made a point to express his dissatisfaction with the culture of policing in Chicago. He has said the consent decree “should lead to our department’s cultural change.”

Last fall, Brown addressed a group of new recruits with a surprising message, telling them they may need to ignore their own trainers and supervisors to do what’s right.

“You may have a trainer or a senior veteran officer where you are assigned who we never should have hired,” Brown said. “Or they started out great and now they lost their way, and their advice to you is the worst advice to take.

“And you’ve got to discern, until they get in trouble and I can separate them from employment, you have to discern not to take their advice,” the superintendent said.

Still, activists say they have not seen meaningful change within CPD since Brown took over.

Northwestern University Law Professor Sheila Bedi, who represents activists in court, said there’s been a “stark” disconnect between Brown’s reformist rhetoric and what she has seen play out on Chicago’s streets.

Bedi pointed to “the incredibly problematic, violent response” to the summer’s civil unrest, the “ham-fisted” handling of a botched raid on social worker Anjanette Young’s home, and the Adam Toledo killing as signs that the department “remains without a strong leader.”

“And, perhaps more importantly, [CPD remains] without a leader that values the lives of Black and brown Chicagoans and who is willing to do what’s necessary to really root out the racism and corruption that infects the department,” Bedi said.

Brown the warrior

A flashpoint in Brown’s handling of protests came in July after a downtown march to Grant Park that called for the city to remove a Christopher Columbus statue there. Police officers scuffled with activists and used pepper spray. One officer took a swing at an 18-year-old activist, hitting her so hard it knocked out a tooth, she said.

An alderman who saw a protester’s video of the clash accused the officers of “protecting white supremacy.”

After two days of such criticism, Brown had heard enough. The top cop called a news conference and played the department’s own video, including overhead clips showing a protester handing out objects the superintendent said were for hurling at officers.

He played other police footage that showed fireworks and bottles pelting cops who were guarding the statute. Brown said the clash injured dozens of officers, including one who suffered a broken eye socket. And he blamed the skirmish squarely on “criminal agitators.”

“Peaceful demonstrations have been hijacked by organized mobs,” Brown said. “Yet, in the face of this action to provoke a violent response, the vast majority of officers have been professional and have exhibited great restraint.”

Recalling Brown’s news conference in a recent interview with WBEZ, a female undercover CPD officer said cops appreciated him having their back instead of “throwing them under the bus like the mayor does.”

“David Brown was clear about who the real enemy in Chicago was,” the officer said. “He blamed antifa.”

But activists said the superintendent’s rhetoric only emboldened abusive cops.

“I think more brazen brutality is what I’ve seen,” Black Lives Matter Chicago director Amika Tendaji said.

Brown’s handling of protests seemed to draw from a decades-old playbook. So did his strategies to address some of the most intense gun violence Chicago had ever seen.

They included diverting resources from the patrol districts to three citywide roving units focused on crime hotspots — a mobile approach abandoned by the department years earlier after accusations of overaggressive policing and a corruption scandal.

Brown promised that the largest mobile unit, the Community Safety Team, would be different because its members would also work on community-service projects, a plan that even some officers on the team have characterized as window dressing. Brown credited the CST for a late-summer drop in shootings.

Skogan, the political scientist, said the city’s violence and civil unrest “probably demanded that the superintendent have some resources available that he could pour into the neighborhood hotspots.”

But shifting those resources from districts around the city upset some aldermen and also some of the roving cops themselves.

“They sent me over to the West Side and I don’t know anything about the West Side,” said a CST member who had worked on a South Side gang unit.

“You see someone with a handgun, they run off, you’re chasing after them without knowing where you are,” the officer said on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to news media. “It’s a dangerous thing.”

A West Side patrol sergeant, who asked not to be named for fear of getting in trouble on the job, called Brown’s return to roving units “out of touch” and said they “broke up existing police-community relationships.”

The sergeant said the mobile units tend to be staffed by less-experienced cops who have been more likely to chase subjects and even shoot them: “Officers with more experience could have avoided those situations.”

Mayers, the police-reform expert, said Brown was reverting to a “warrior” style of policing in which cops “look for the next opportunity to make an arrest and use force.”

“He’s doing what most police departments are doing,” Mayers said, pointing to short-term steps against crime that are easier than efforts in which “community members are going to be a part of supporting public safety.”

Involving community members, Mayers said, is a steep climb “but we’re going to get long-term sustainable results.”

With Brown’s old-school approaches came old-school rhetoric that sought to shift blame for the violence to judges and prosecutors.

“Our cops are working hard,” Brown said at a press conference following a particularly violent weekend in June. “There are too many violent offenders not in jail.”

Pointing the finger at the court system is an old habit of Chicago police leaders — and mayors including Lightfoot — and Brown kept at it throughout his first year.

On June 29, as Chicago braced for its annual spike in gun violence during the Fourth of July weekend, Brown announced a CPD plan to arrest teenagers on “drug corners” in the days before the holiday.

“Our endgame is arrests for the precursors to violence,” Brown said. “So, every day we’re going to be clearing the corners … to protect these young people from violence. But, when we clear the corner, we’re pleading with the court systems, keep them in jail through the weekend.”

“If we make an arrest Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, we’re pleading [for the teens to be held] through the weekend, at least,” Brown said. “Let’s protect these young people.”

Brown’s plan to lock kids up to protect them did not go over well with civil-rights attorneys.

Lightfoot, asked about it by reporters, said the pre-holiday arrest targets were adults and denied Brown had discussed sweeping up kids.

Brown tried to walk back his words but, throughout his first year as superintendent, he struggled to address Chicago’s gun-violence surge without undermining his goal of building trust between cops and heavily policed communities.

Brown’s latest test

As Brown starts his second year on the job, none of the competing demands on him show any signs of abating.

Shootings and murders are up again this year. The police killing of Adam Toledo, the 13-year-old, prompted large street protests and, though former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin’s conviction appeared to avert another spate of protests in Chicago, the demands of CPD’s consent decree and the outrage of activists are not going away.

After Adam’s killing, Brown and Lightfoot talked up plans to craft a new foot pursuit policy for Chicago officers to prevent the kind of dangerous encounters that can end in the death of a child.

It’s an issue Brown inherited — the department has been on notice since at least 2017 that its lack of a foot chase policy puts officers and residents in danger — and the renewed urgency to create the policy puts the superintendent on another tightrope.

Activists believe CPD needs to implement a policy strict enough that it would ensure something like Adam’s killing could never happen again.

But Brown, who declined an interview request for this story, must balance those concerns about police violence with the worry of limiting officers as the city grapples with high levels of armed violence and as another potentially bloody summer approaches.

Last summer Brown attempted to unite a divided city with his words of compassion, but now he has been mostly absent from the public eye during what seems like a particularly fraught time for policing in Chicago.

Brown waited until four days after it was revealed that one of his officers had killed a 13-year-old child before he addressed Chicagoans on April 5.

He hasn’t spoken publicly since.

Patrick Smith and Chip Mitchell report on criminal justice for WBEZ. Follow them at @pksmid and @ChipMitchell1.