Beverly Kumar knows which bakeries and restaurants in Chicago offer some of the flavors that take her back to Mumbai, the city in India where she grew up. These businesses are clustered on a mile-long stretch of Devon Avenue from about California Avenue on the western edge to Damen Avenue on the east in the West Ridge neighborhood. This area is commonly known as Little India.

Kumar, a board member of the National Indo-American Museum, visits every time she has a taste for a traditional Indian fudge called Kalakand, made with milk and cardamom.

“It’s very comforting knowing that just ... 14 miles away from my house, there is an essence of Little India, it's nostalgia for me,” Kumar, who lives in North Suburban Northbrook, said. “With the familiar sights, smells, sounds, you know, flavors of home … I feel like I never moved away after all.”

This neighborhood is one of the most diverse places in the city, with immigrants from many parts of the world. It’s also a hub for dozens of South Asian businesses, including grocery stores, sari and jewelry shops. Like Kumar, many visitors from other parts of the city, and across the region go to Devon Avenue for a day of shopping or dining.

Curious City listener Munjot Sahu, who lives in Zionsville, Ind., but was born in Chicago, wanted to know: How did Devon Avenue become a primarily Indian community?

Chicago’s metropolitan area has the second-largest Indian population and the fourth-largest Pakistani community in the U.S., according to 2019 census data analyzed by the Pew Research Center. But two big migration waves from South Asia contributed to demographic shifts in the area.

Still, there is a lot more to unpack here. To answer Sahu’s question, we met up with people in the community who have lived through several transformations and migration waves in the area in recent decades.

A demographic shift influenced by the first South Asian wave

The community around Devon Avenue wasn’t always home to Indian and other South Asian residents. Actually, back in the 1950s and 1960s, the neighborhood was mostly Jewish. There’s still a Jewish community there today. It just isn’t as big as it once was. But there are trademarks of their presence, including an honorary street sign named for Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir. There are still bakeries, synagogues and a Jewish community center nearby.

The first wave of immigration from South Asia came with the passage of the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 — a piece of legislation that opened the doors to highly-skilled immigrants. It attracted many professionals to resettle here in Chicago, including doctors and engineers.

Among that first wave was Ranjana Bhargava, who arrived in the summer of 1968. She had a master's in psychology. She remembers how hard it was to find vegetarian food in Chicago back then.

“You know, we went to McDonald's. So we would say, give me a hamburger without a burger,” Bhargava said. “And they would look at you. And they would say, ‘What do we charge?’ They didn’t know what to do with us.”

Bhargava was in her 20s. She says she wasn’t much of a cook back then. But, as she learned to make traditional dishes from Northern India, she had to figure out where to get some of the spices she needed and weren’t that popular, including cumin and paprika.

“There was no Indian store,” Bhargava said. “There was no Indian restaurant in Chicago at that time. Mexican places had some of those spices. And we could smell it and feel, ‘Yes, they are the right ones.’ ”

She and her husband have lived on the South Side for decades, but she worked in Little India for many years. She witnessed how the neighborhood became an anchor for the Indian community. And she remembers when things started to change.

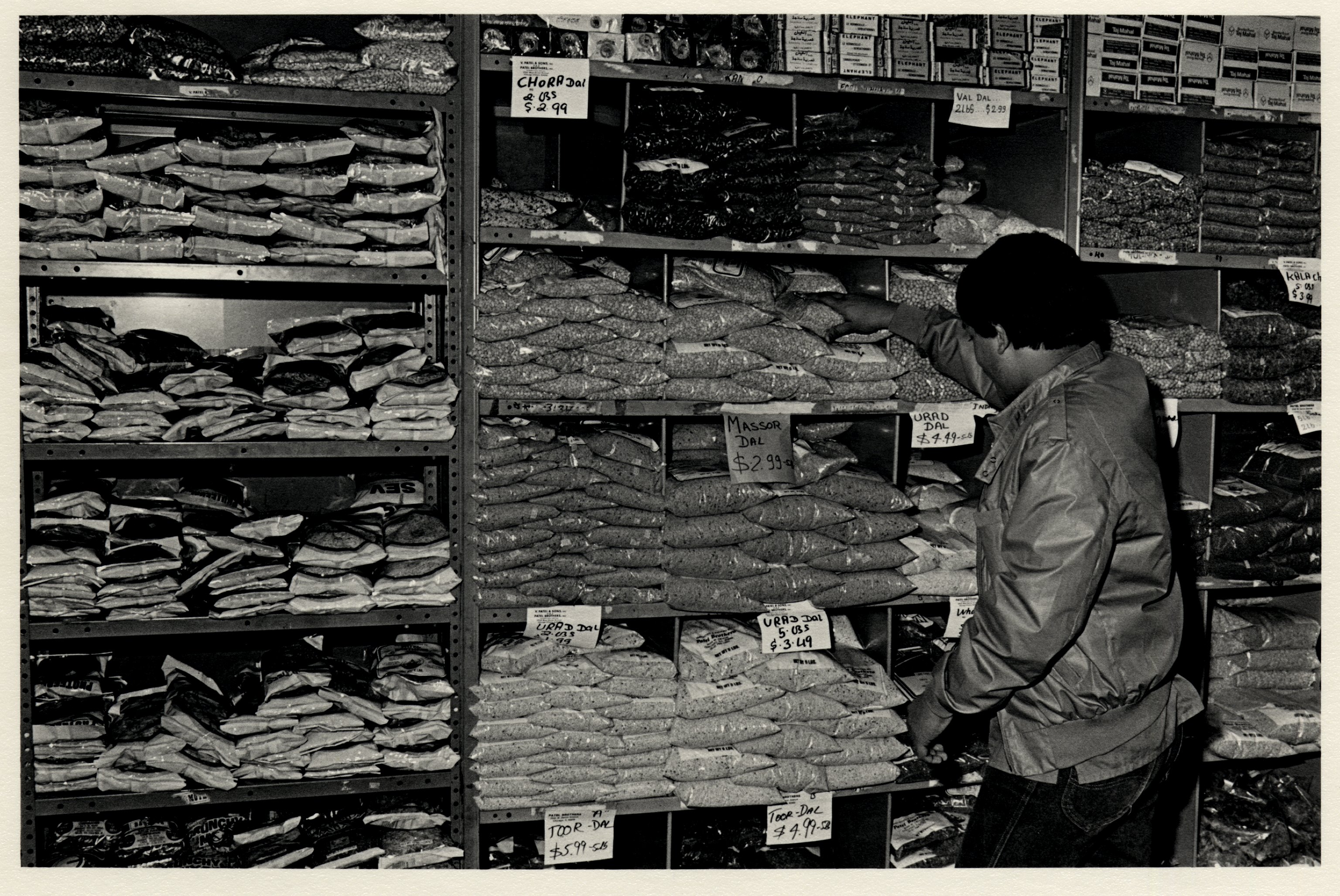

She was thrilled when the first big Sari store opened up on Devon Avenue — The Sari Palace — followed by other Indian shops primarily centered around Devon Avenue, including the first Indian grocery stores, like Patel Brothers, which opened in the ‘70s.

Along with the new stores came new residents and community. Once a month, a local theater played Indian movies. There were also social gatherings where people shared food, played instruments and performed traditional dances.

Little India comes into its own

In the 1980s and 1990s, there was a second wave of South Asian migration made up mostly of relatives sponsored by family members who came in the 60s.

And as more Jewish families moved out of West Ridge into the suburbs, South Asians took over their vacant storefronts.

“People started saying, ‘Oh, we can open a store,’” Bhargava said. “So there was a jewelry store and electronics was a very big thing.”

And as Bhargava said, at some point it seemed like every other taxi driver in Chicago was Indian or Pakistani.

As the area thrived with new stores and more people, visitors started coming from around the city and suburbs to sample the cuisines of India and Pakistan. But to outsiders it was just that — a taste of India in Chicago.

Bhargava said most Chicago residents lump South Asians into one nationality — Indians. But there are also residents in the area from Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Bhutan and many other countries outside South Asia, including Croatia and Syria.

By the early 2000s this strip had become more of a place where South Asian families came to shop and eat before going back home to the suburbs. Some residents couldn't afford to buy a home in the area. Other families had a choice. For them it was a sign of prosperity to move to the suburbs.

Devon Avenue today

Today it's hard to label the community as Little India, said Chirag Shah, community navigator program manager at the Indo-American Center. “A lot of businesses do serve a lot of the South Asian population,” he said. “But as we walk up and down Devon … you come across people from 10 different countries.”

Shah, who grew up in the neighborhood, said the staff at the Indo-American Center speak about 15 different languages, but he estimates there are twice that many languages spoken in the community.

With so much going on in a relatively small area, hostilities from back home sometimes surface in the community, especially among Indians and Pakistanis.

“There'll be these moments during the Pakistan in India parade where …young teenage boys had their nationalism moments,” said Mueze Bawany, whose family moved to the neighborhood in 1990 from Pakistan when he was 3 years old. “We used to have some fist fights that will break out.”

But aside from parade disputes and disagreements over cricket matches, Bawany, who is an English teacher, said those tensions never lasted long. He is also running for alderman of the 50th ward, which covers a large part of the area known as Little India.

Bawany grew up with friends who were orthodox Jews, kids from India, who were either Hindu, Sikh or Jain. He had friends from Kosovo, Somalia and Syria.

Anecdotally, West Ridge is one of the last remaining points of entry on the North Side, according to Shah and other people working in the community. They say in the last few years, more immigrants, including South Asians, have been coming without resources and many are undocumented. Some are fleeing conflict, genocide and poverty.

They come to this neighborhood because they feel a sense of belonging, Bawany said.

“You can pray here, you can be your culture, wear a sari, wear a headscarf, be as close as you could be to home here,” Bawany said.

That’s the type of diversity people can see on Devon Avenue today. Still known as Little India, at least for now. Still attracting new waves of immigrants to live and still bringing in visitors from the suburbs and beyond to sample some of the best South Asian food.

Adriana Cardona-Maguigad is a WBEZ reporter. Follow her on Twitter @WBEZCuriousCity and @AdrianaCardMag.