Editor’s note: This story contains descriptions of violence.

Floyd Webb remembers the first time he met John Keehan. It was 1964, and Webb was just 10 years old, scrubbing out garbage cans in an alley in Chicago’s Chinatown to earn pocket money. Webb was living on the other side of the expressway in the Harold Ickes housing project.

On this particular day, behind a row of restaurants, Webb and his friends noticed a guy putting up posters. They’d seen him around before — he was a red-haired guy in his 20s, memorable because he was a white person who was actually friendly to them, a group of Black kids. “We usually got thrown out of places when we left the neighborhood,” Webb said.

The man introduced himself to the boys as John Keehan. The posters he was putting up were for a karate tournament taking place just a few blocks from where Webb lived. The idea of going to the event exhilarated him.

Used to getting bullied by his classmates because he was scrawny and spoke with a stutter, Webb spent a lot of time daydreaming about sticking up for himself. He loved action movies with fight scenes, and when he was home alone, he often mimicked the judo-inspired moves he’d seen.

But when it came to joining a formal martial arts school, which were then becoming more popular around the country, Webb had a problem. Most martial arts schools at the time excluded Black people. On top of that, in a city like Chicago — which was then an incubator for a burgeoning Black Power Movement — teaching Black people to fight was considered taboo.

“The cops didn’t want Black and Hispanic people learning martial arts,” Webb recalled.

When they arrived at the tournament, the boys couldn’t believe their eyes.

“Instead of a three-ring circus, it was like a 12-ring circus,” Webb said. There were throngs of people gathered around matches taking place across the arena.

Keehan took the boys over to one of the matches and led them up to the front of the crowd. As the men fought round after round, Keehan told Webb and his friends about the fighters and talked them through the match.

Webb was in awe of Keehan. He brought Webb into a world he wanted to be part of. And he made him feel like an insider.

It’s what led Webb, as an adult, to spend more than a decade and a half working on a forthcoming documentary about Keehan’s life. Keehan ran successful dojos, or martial arts schools, and tried to change the very nature of martial arts competitions in the United States.

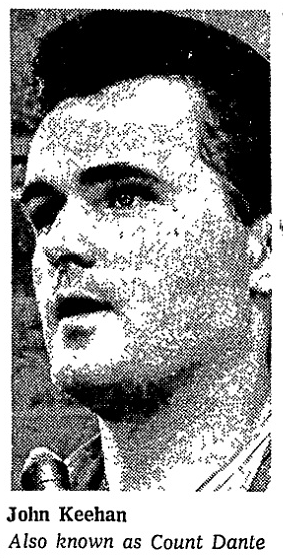

So when Curious City listener CJ Fraley asked about the infamous dojo wars in Chicago, we first turned to Webb, who has arguably the most comprehensive knowledge of the time. There were, in fact, intense rivalries between dojos in the city during the 1960s and ’70s. We also talked to a number of people who knew Keehan personally about the man at the center of these wars. Keehan helped popularize karate in Chicago, but his ego eventually led him down a path of self-destruction. This is his story.

Keehan was born in 1939 to an Irish-American family. Before he became a martial arts legend, he was a skinny kid growing up in Chicago’s Beverly neighborhood.

One night, someone broke into his family’s home, and Keehan, a teen at the time, confronted the intruder. Instead of stopping him, Keehan got beaten up.

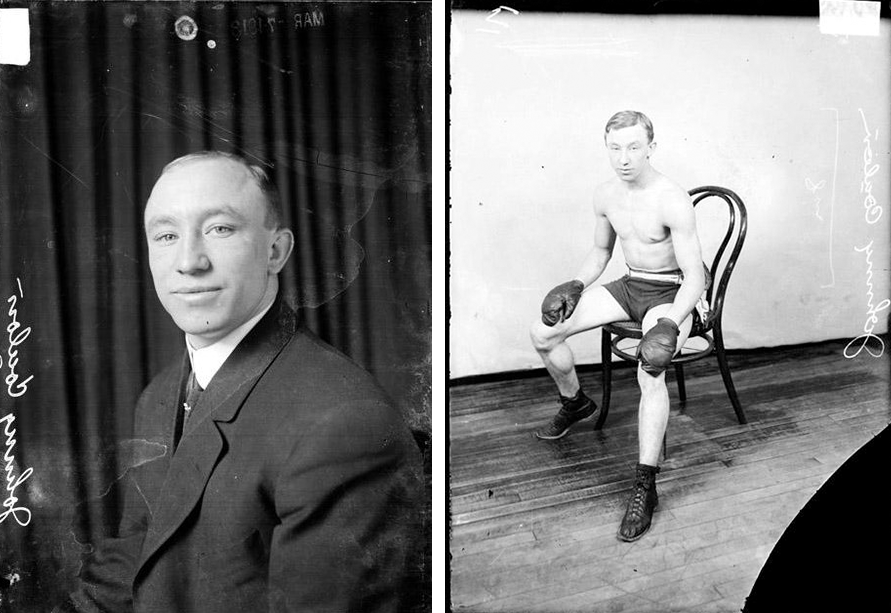

After that, Keehan’s dad decided his son needed to be able to defend himself. He signed Keehan up for boxing lessons with Johnny Coulon, an Irish-American boxer who ran a gym in Chicago's Woodlawn neighborhood.

Fighting, to Coulon, was the great equalizer, and showed what you were truly worth. “If you came into Johnny Coulon gym and had a problem with Black boxers being there, Coulon would tell them, ‘Get in [the ring] with ’em, let's see what you can do,’” Webb said.

Because he spent so much time in places like Coulon’s gym, Keehan ran in more diverse circles than most kids in his neighborhood, which was majority-white at the time.

“Some of his friends would tell me that they were always shocked they would go out with John, and John would … go on the South Side to Black parties and everybody knew him,” Webb said.

After graduating high school in 1968, Keehan joined the military. He’d loved boxing since he was a teen, but it was while he was stationed in California in the Army that he became obsessed with martial arts. He read books about martial arts techniques, started training in kung fu and spent time with karate masters up and down the West Coast.

Keehan seemed hell-bent on getting discharged from the Army. According to his friend Tommy Gregory, Keehan stole cars, made false reports to police and even went AWOL for a while to try and get tossed out.

In 1960, Keehan finally got kicked out of the Army. Freed from his military duties, Keehan made his way back to Chicago and devoted himself to martial arts full time.

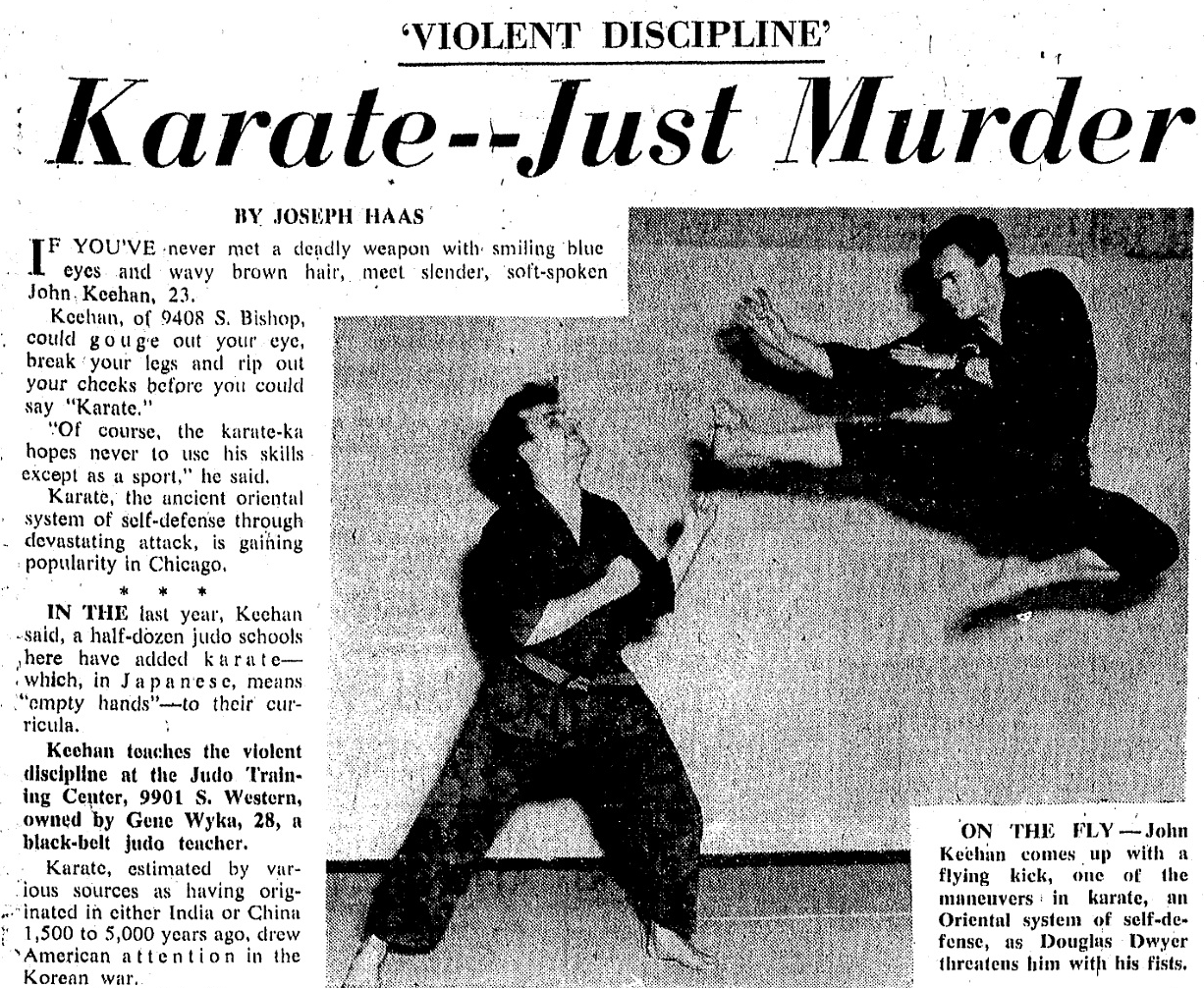

Karate was introduced to the United States in the 1940s and ’50s, partially driven by World War II and Korean War servicemen bringing fighting techniques back from abroad.

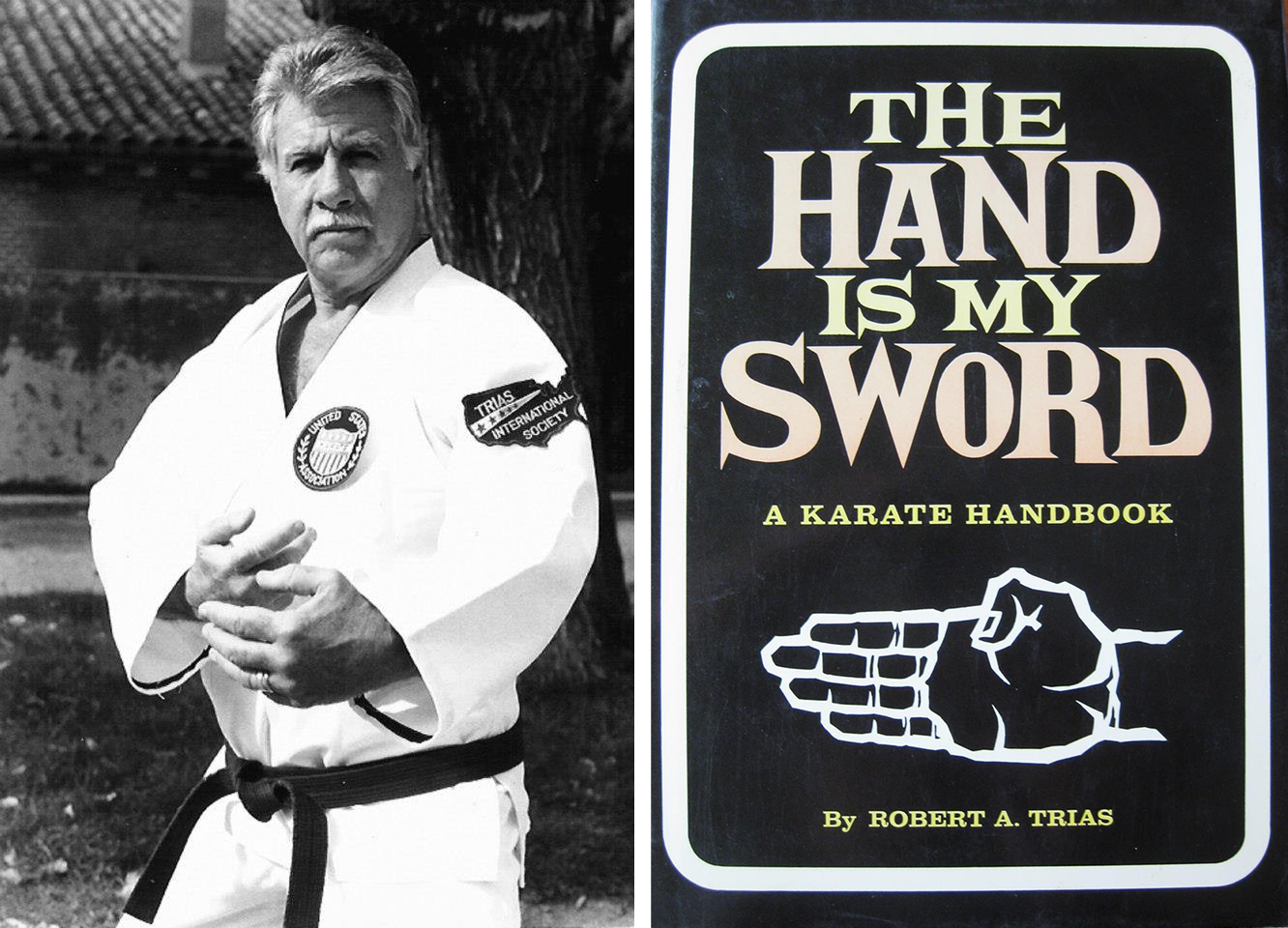

Robert Trias, often referred to as the “father of American karate,” was the first person to open a public karate school in the U.S. He opened his dojo in Phoenix, Arizona in 1946 and founded the country’s first national karate organization, the United States Karate Association (USKA), just a couple years later.

Keehan started training with Trias as soon as he returned from the Army. He drove from Chicago to Arizona and stayed for weeks at a time, renting rooms at fleabag motels and training during the day.

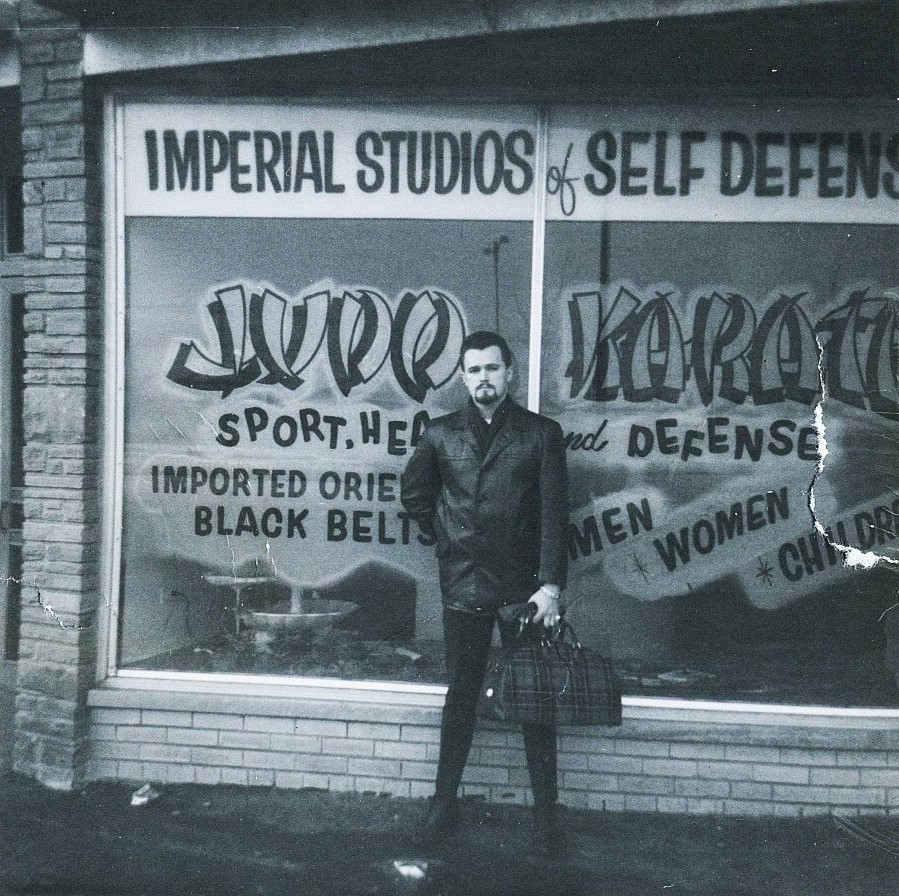

By 1962, Keehan had opened his own dojo in Chicago, the Imperial Academy of Fighting Arts. The school had two locations: one was in the Beverly neighborhood, where Keehan grew up. The other was on Rush Street in the Gold Coast. At the time, Rush Street was like Chicago’s Las Vegas strip, full of neon lights, bars and burlesque clubs.

Most of the guys Keehan trained were construction workers and people from around the neighborhood. He put them through rigorous boxing regimens he’d picked up from Coulon and taught them martial arts moves he’d learned from Trias.

Now in his mid-20s, Keehan was focused on creating a larger-than-life persona for himself. He drove fancy cars, wore expensive clothes and walked up and down Rush Street with his highly unusual pet: a lion cub named Aurelia he’d bought downstate.

His friend Tommy Gregory remembers the lion cub particularly vividly. “That f****** thing would absolutely tear the s*** out of you,” Gregory said. “It was as wild as can be.”

And he fell in love. In 1964, Keehan met a woman named Pat Harpold at a bar. He proposed within a few months of dating.

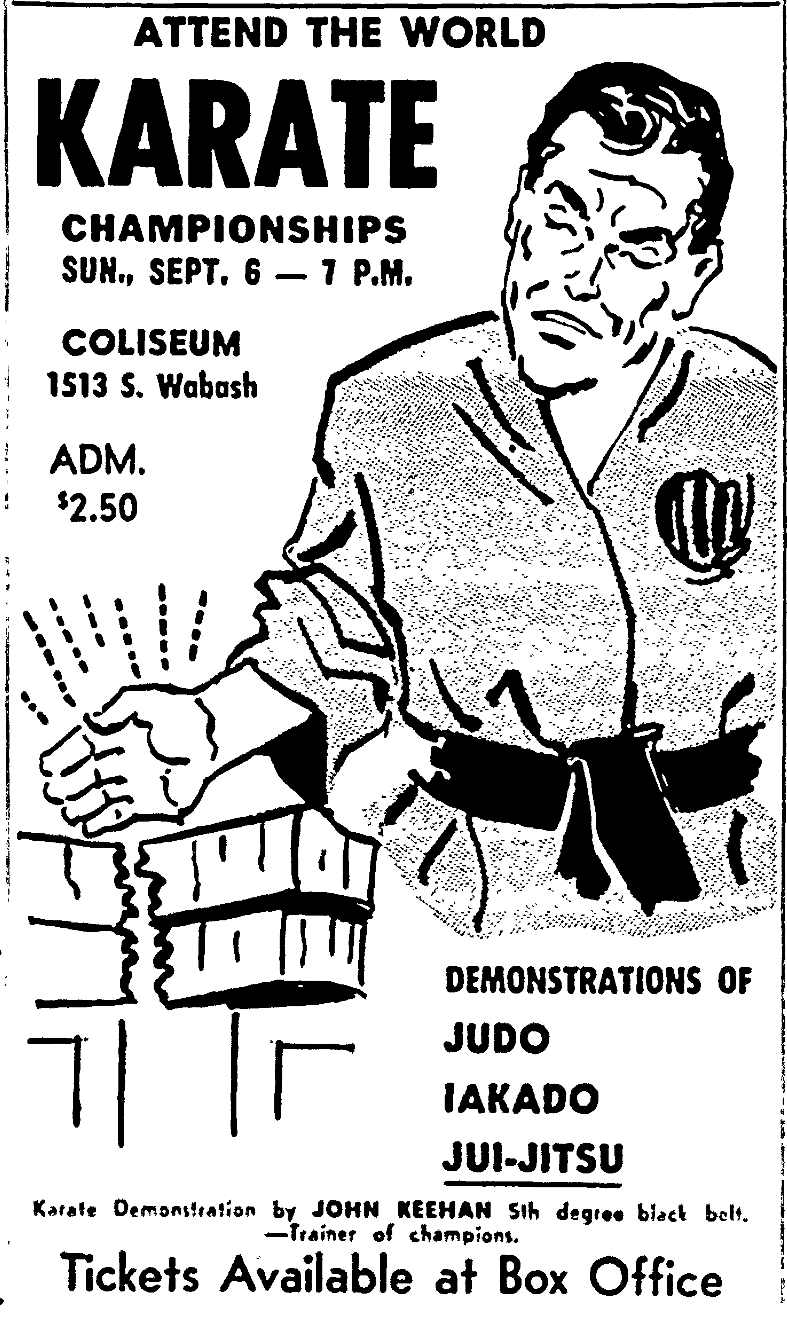

Keehan’s importance in the U.S. martial arts world was rising fast. In 1963, he and Trias had organized a successful karate tournament in Chicago. They planned another, even bigger tournament the following year.

For Trias, the Chicago tournaments were part of an effort to expand the reach of the USKA. For Keehan, they gave him an opportunity to solidify his own reputation as a promoter, showman and karate master.

And they put Chicago on the map as an epicenter of martial arts nationwide.

But at this point, despite having one successful tournament under their belts and another on the horizon, things between Keehan and Trias were tense.

Keehan’s boxing mentor, Coulon, had believed anyone was worthy of being in the ring as long as they could fight. But Trias didn’t feel the same way. Keehan’s best fighter at the time was Raymond Cooper, who was Black. And Keehan had given black belts to a number of his Black fighters — something he saw as the biggest issue between himself and Trias, according to Webb.

But it wasn’t just who they put on the mat that Keehan and Trias disagreed about. It was also how they trained them to fight. “We're watching things like people's teeth get knocked out,” Webb remembered of the 1964 tournament, where he saw many of Keehan’s students up close for the first time. “For a no-contact tournament, there was a lot of contact.”

In a CBS News interview from just before the 1964 tournament, the reporter stands in front of the karate school’s logo, a giant black dragon. The reporter asks a confident-looking Keehan whether someone can be seriously injured doing karate. Keehan responds, “You can very easily kill someone, if you know how to hit them and where to hit them.” He pauses and then adds, “This is the whole thing [that puts] the trained over the untrained.”

Rather than going for knock-outs, like in boxing, a fighter in karate matches typically pulls their punches and kicks — coming mere inches from striking their opponent. Judges award points based on technique, and fighters can lose points, or even be disqualified, for making contact.

But for Keehan, none of that mattered if you couldn’t win a fight in the real world.

“You didn’t know what you knew until you actually went out and fought somebody,” Webb said of Keehan’s philosophy.

Frustrated by the sport’s no-contact rule, Keehan started his own organization, a competitor to the USKA called the World Karate Federation that allowed for more contact between fighters. (Keehan’s organization is unrelated to the World Karate Federation that exists today.)

Art Rapkin, one of Keehan’s former students, said trainees hoping to advance to brown or black belts were put in a dimly lit room and forced to fight four other students from their dojo — one after another, at full force. They were given sticks and knives, and let loose. By the end of this initiation ritual, people were left bruised and bloody.

And Keehan would intentionally instigate bar fights, enlisting unsuspecting people to help with the beat-in. Rapkin said Keehan would find the biggest guy at the bar, knock a beer bottle out of his hand and blame his trainee for it.

“John would look at me and go, ‘Why the f*** did you actually do that?’ in front of the guy,” Rapkin recalled.

“If he was with four guys, you’d have to fight them, too,” he said.

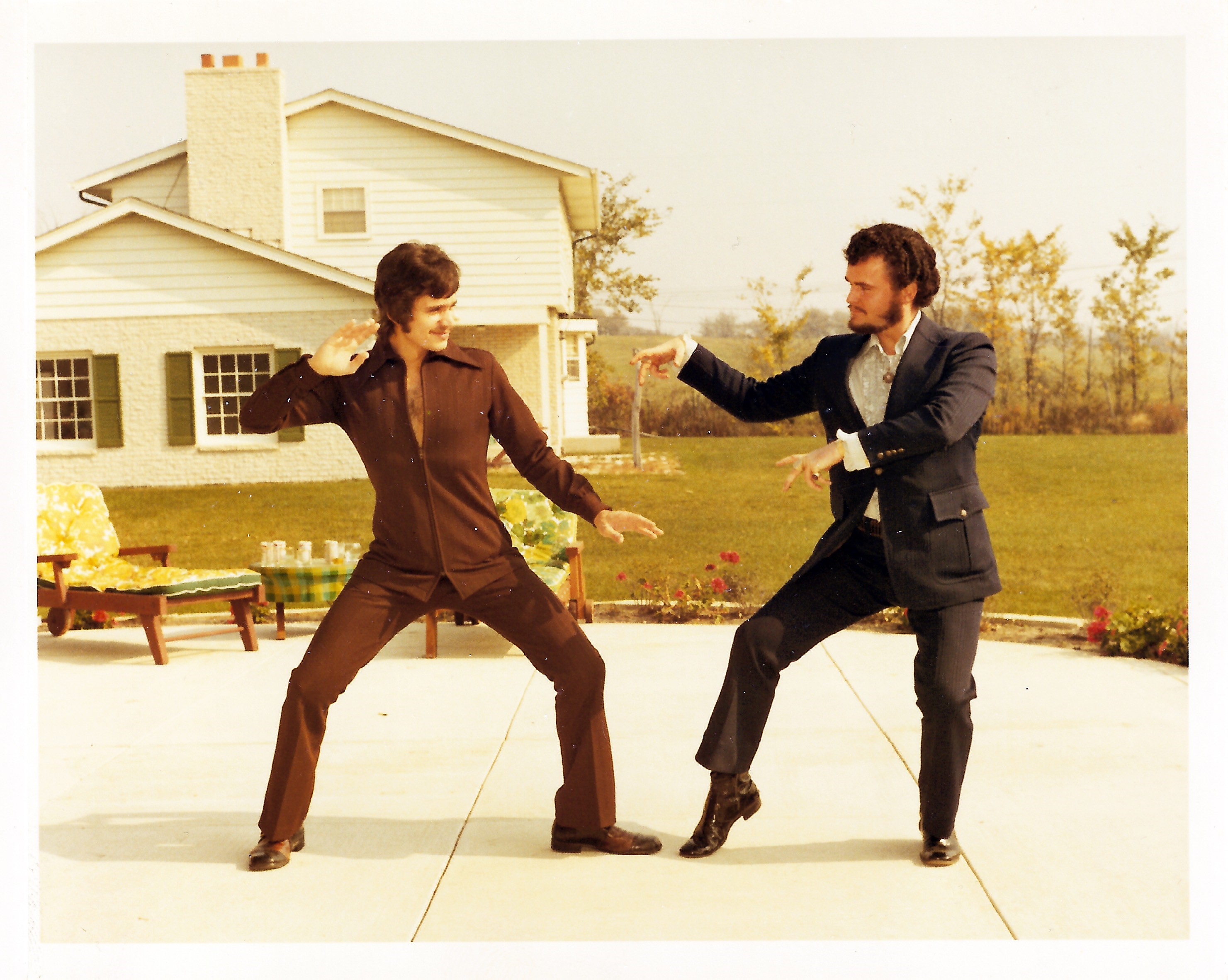

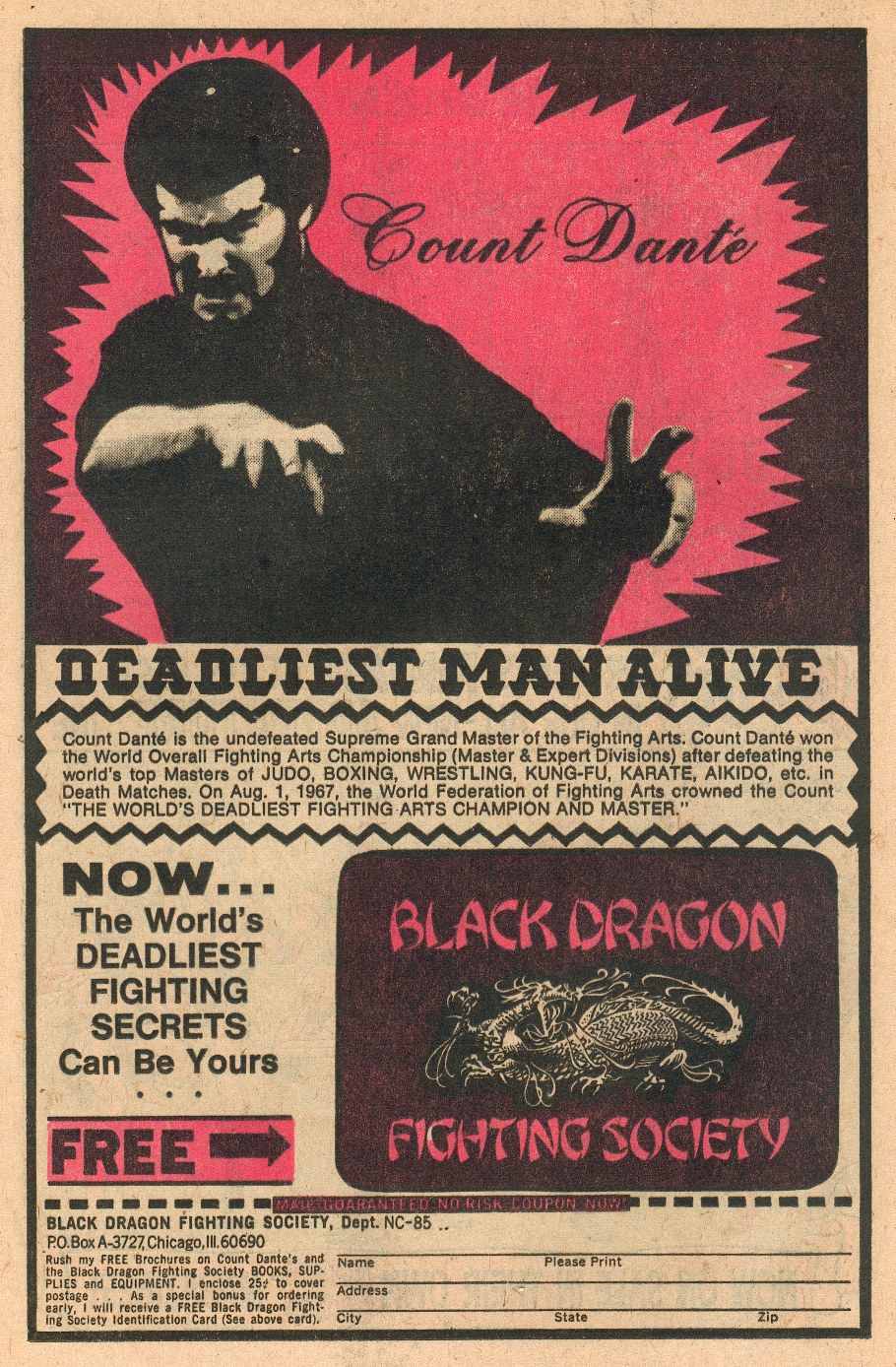

By the mid-1960s, Keehan had amassed a following of elite martial artists. He called these followers the Black Dragons.

The Black Dragons proved their mettle against other martial arts schools around the city in off-the-books battles. And because of Keehan’s own penchant for violence, when the Black Dragons got involved, the brawls were often bloody.

“Those fights were like Tarantino movies,” Rapkin said. “Think Kill Bill.”

These ongoing battles became known as Chicago’s infamous “dojo wars.” Violent from the start, within a few years, they would turn deadly.

Meanwhile, Keehan continued to add to his already mythic persona.

He legally changed his name to Count Juan Raphael Dante and began claiming to have descended from Spanish royalty. He wore a velvet cape and carried a gold cane with a lion’s head on its handle.

At home, he was increasingly prone to angry outbursts. “He lived in a fantasy world of things he wasn’t,” Harpold said. Keehan had to rehome their pet lion after it got too big and fierce for him to take care of. Harpold says their marriage dissolved, and by 1966 they were divorced.

Keehan started dating a waitress from the Playboy Club and turned her into a character, too. The Dragon Lady, as Keehan dubbed her, became a kind of sidekick to Count Dante. She was known as a Playboy Bunny with a black belt — though she had limited karate skills. They appeared together on tabloid covers and local television shows, performing acts that were a combination of martial arts and magic tricks. It was all part of a promotional ploy.

“He wasn't satisfied with just being a successful, well-respected martial artist,” Rapkin said. “He also wanted to be, like, Elvis.”

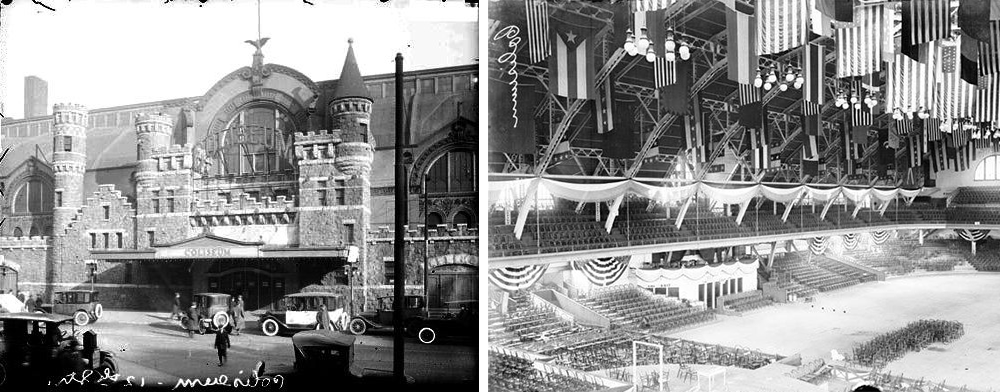

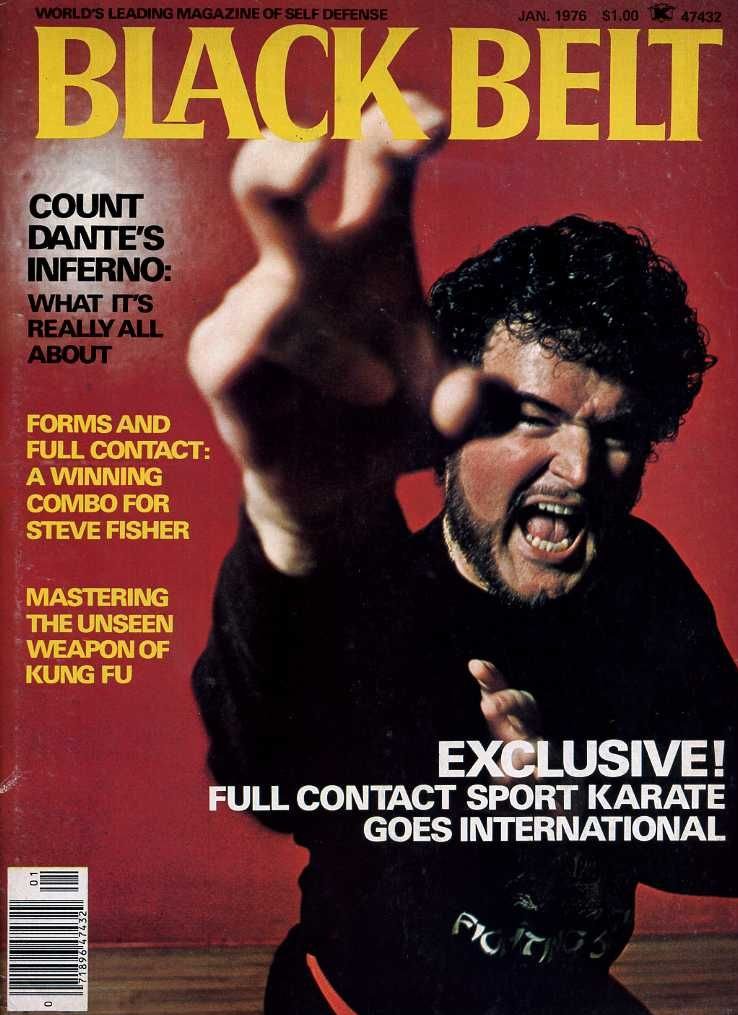

In September of 1968, Keehan held the first major full-contact karate tournament in the United States. At the World Fighting Arts Championship Tournament, virtually any move, no matter how aggressive, was allowed. It took place at the Chicago Coliseum, where Keehan had co-hosted a tournament with his former mentor several years earlier.

The fighting was fierce, but — perhaps in part because he was on the outs with the larger martial arts community — ticket sales were lower than Keehan expected. By the time the tournament was over, he owed a lot of people money he didn’t have.

According to Rapkin, Keehan was desperate to get off the hook for the money he owed, so he got creative. “‘What you're going to do is you're going to take the money and then you're going to report to the police that you got robbed by a couple of guys with a shotgun,’” Rapkin said Keehan told him. “And I did that.”

The physical violence that marked Keehan’s martial arts career began to leak out at home.

“She came to my house with two black eyes,” Harpold recalled of the night the Dragon Lady showed up at her door. After getting beat up by Keehan, the Dragon Lady found Harpold, hoping to talk to someone who knew Keehan the way that she did. And though Harpold said Keehan was never physically abusive with her, she was familiar with his outbursts.

At this point, Keehan was a powder keg. He had no mercy for anyone who stood in his way.

The Chicago dojo wars raged on.

One of the Black Dragons’ biggest rivals at the time were the Green Dragons, who trained at a dojo on Fullerton Ave. in Logan Square.

Keehan had already landed on the FBI’s radar after he tried to blow out the front windows of a rival martial arts school using dynamite a few years earlier. And things were about to get even worse.

Late in the evening on April 23, Keehan showed up at the Green Dragons’ dojo with some of his best fighters.

According to Patrick Garrison, a Green Dragon who was there that night, Keehan knocked on the door of the dojo and pretended to be law enforcement. As soon as the door opened, the Black Dragons stormed in.

The Green Dragons immediately grabbed their own weapons off the walls: samurai swords, battle axes and maces — spiked steel balls on the end of long wooden sticks.

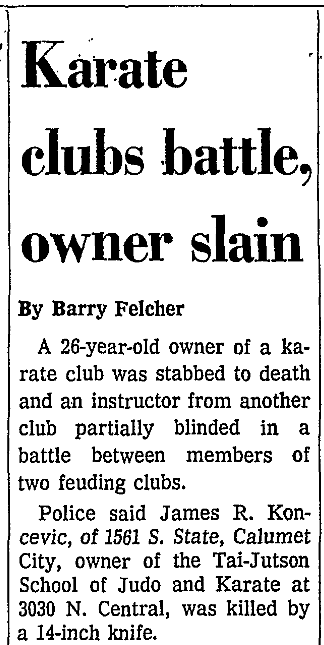

One of the Black Dragons fighting beside Keehan that night was Jim Koncevic. At 6’2’’ and 265 pounds, Koncevic was a judo champion and legendary brawler. He also ran his own martial arts school in the Belmont Cragin neighborhood. The two were best friends.

Green Dragon Jerome Greenwald later told the Chicago Tribune that Koncevic attacked him from behind, hitting him right in the middle of his back. Trying to defend himself, Greenwald said he grabbed a dagger from the wall and turned to face Koncevic. In what Greenwald swore was an accident, his 14-inch knife plunged straight into Koncevic’s body.

Keehan’s friend staggered out the front door of the dojo and collapsed on the street. “You could swim through [the blood on] that sidewalk,” Garrison said.

Koncevic died from his injuries. Greenwald was charged with manslaughter and Keehan was charged with assault and battery, among other things, for instigating the attack.

When the case finally went to court, the judge dismissed all charges. According to Keehan’s attorney, Bob Cooley, who documented the events in his book When Corruption Was King, the judge screamed, “You’re each as guilty as the other. I’ve never seen such a pack of lunatics!”

But the fallout from Koncevic’s death came swiftly from the martial arts community, which shunned Keehan.

Over the years that followed, Keehan ran a used car dealership, a porn shop and a hot dog concession at Comiskey Park. He hovered at the edge of organized crime. In the fall of 1974, he was questioned in connection with the Purolator vault heist — the largest cash robbery in the U.S. at the time. He was never charged for it.

And then, in May of 1975, at just 36 years old, Keehan died. For a man who lived so much of his life in sensational terms, the circumstances of his death were surprisingly uneventful. He died at home alone in his Edgewater apartment. And though people speculated wildly about what led to his death, the official report stated that Keehan died from a bleeding ulcer.

Keehan’s impact on martial arts in the United States was huge but complicated. He took what he learned from the boxing gym of his youth and believed it was a person’s physical ability — rather than their race — that made them worthy of competing.

For documentarian Floyd Webb, what stands out about Keehan is the number of Black students that successfully trained in his dojos.

“He had welcomed Black students in his school and those Black students were taking all the championships at that point,” Webb said. At the same time, Webb believes reckoning with Keehan’s legacy is fraught because of how violent Keehan became. “You keep opening these doors and you keep finding out different things about the guy.”

Keehan’s emphasis on physical toughness as the ultimate sign of a person’s worthiness led him to push for more contact in martial arts — a precursor to sports like today’s mixed martial arts. But this same obsession led him to never back down, instigate deadly battles between dojos and made him volatile at home. For better or worse, he’ll be remembered as a main character in the history of Chicago’s martial arts scene.

Joe DeCeault is a senior audio producer for WBEZ. Follow him @joedeceault.