The Medinah Temple reopened its doors earlier this month, this time as a casino. The building at the corner of Wabash and Ontario Streets in Chicago’s River North neighborhood will be home to Bally’s, the city’s first-ever casino, until a permanent location is constructed in River West.

The temple’s onion-shaped domes, horseshoe arch and Arabic inscriptions got one Curious City listener wondering about the history of the Medinah Temple, as well as the community after which it was named.

The Medinah Shriners are the Chicago chapter of Shriners International, a fraternal organization founded in New York City, associated with Freemasonry. They built the temple in 1912 and used the building for events like the famous Shrine Circus, private raucous bashes and even ice shows throughout the 20th century. They also rented the space to outside parties like television station WGN and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The building has hosted some of Chicago’s most celebrated events across the 111 years it’s been standing.

Today, the Medinah Shriners are based in suburban Addison. But this somewhat obscure organization played an integral role in not just the design of the building but also many of the events that took place there — some of which are inseparable from the history of the city itself.

The Shriner aesthetic

The Shriners are an offshoot of the Freemasons, a fraternal movement that originated in Europe and has historically been associated with secrecy and ritual.

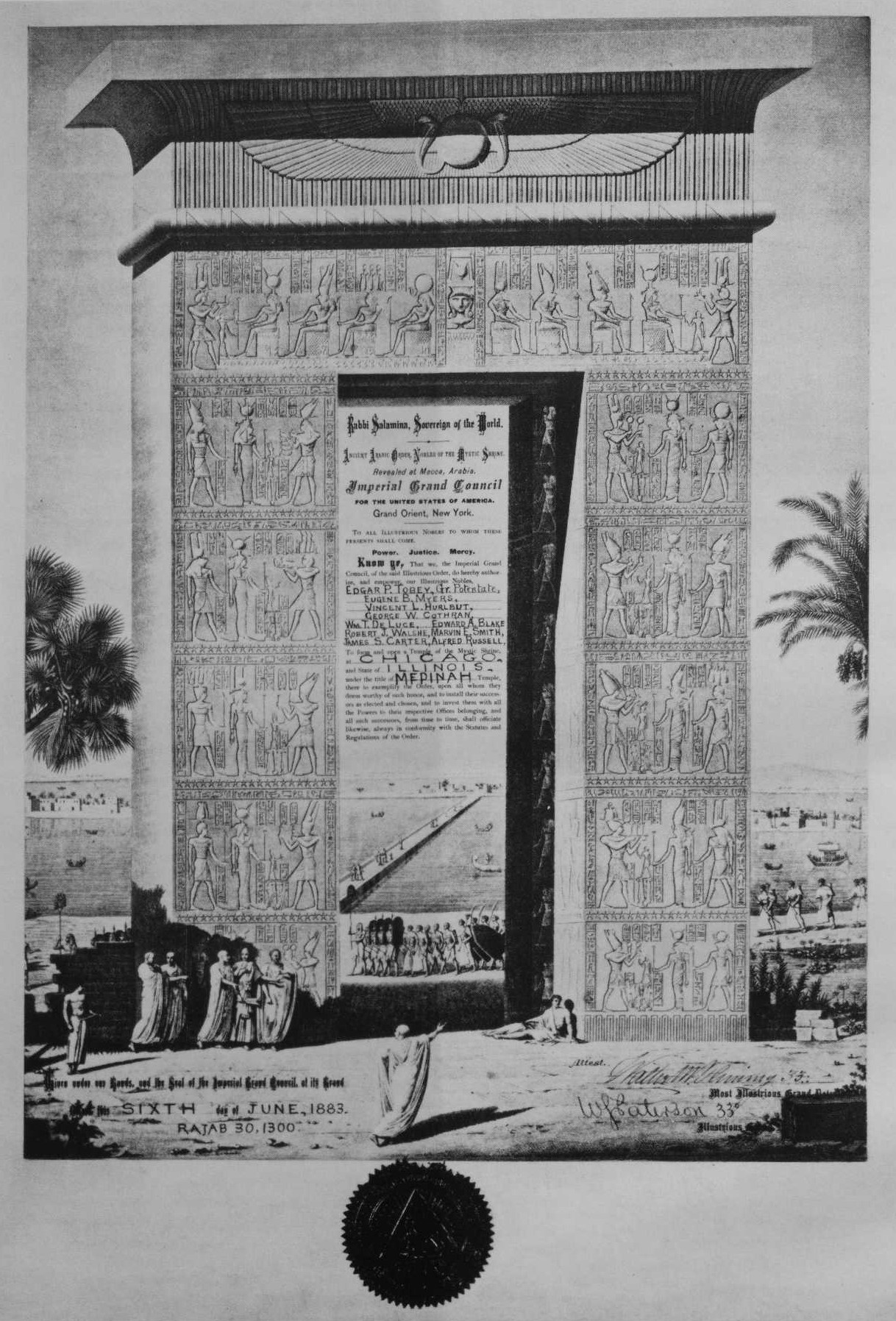

The Shriners came to Chicago not long after the organization’s founding, creating their first permanent home in the city in 1883.

In order to become a Shriner, members must first be Freemasons. Freemasons require new members to meet several criteria, including being adult men and being religious in some capacity. (They can be of any faith, though Freemasonry is mostly associated with European Protestantism.) Longtime member Paul Barber described the Medinah Shriners as a non-religious organization, “but Masons are religious men.” Masons in good standing must perform several additional rites and rituals in order to join a Shrine.

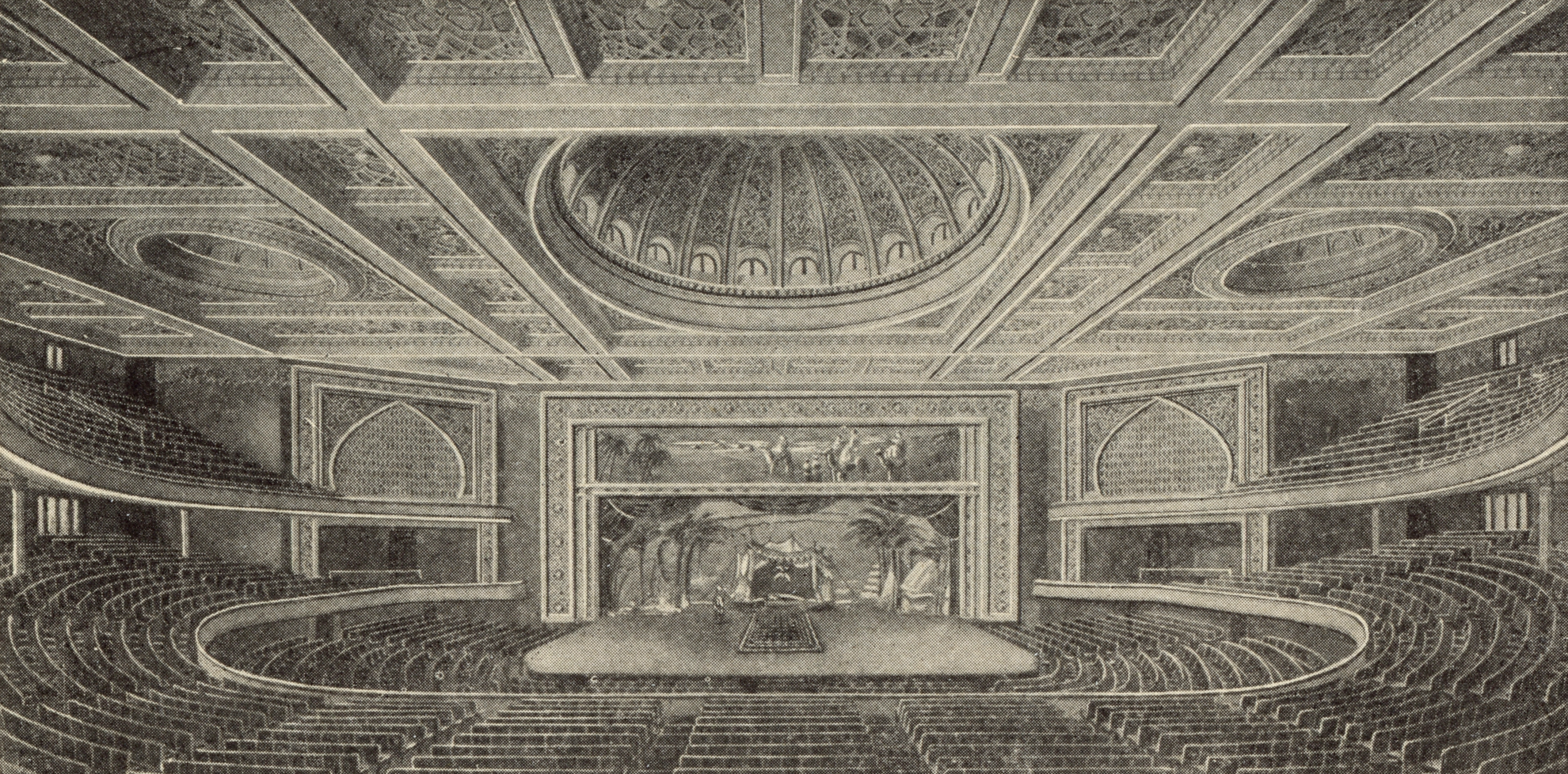

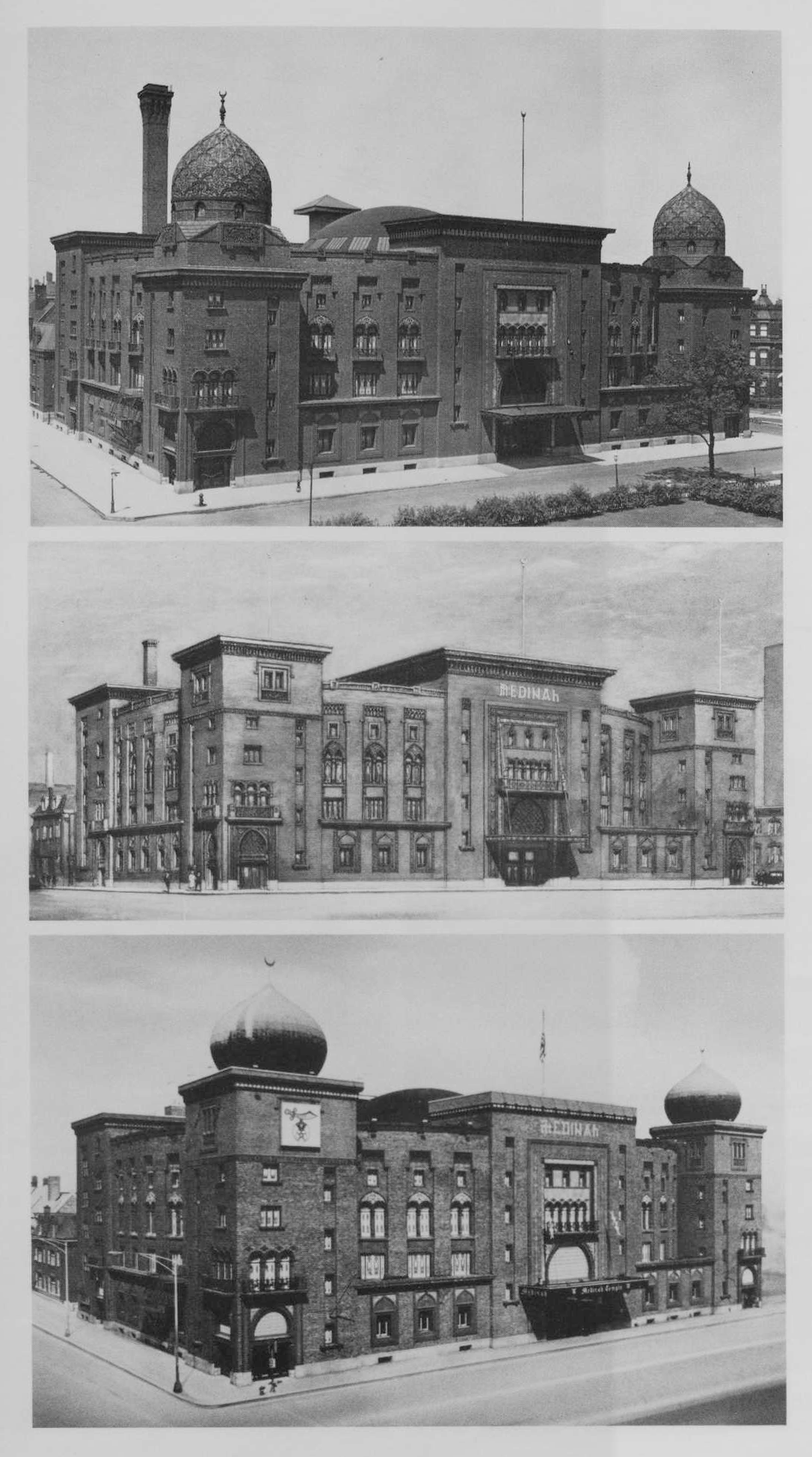

The Medinah Temple that stands today was constructed in 1912 by Shriners Harris Huehl and Gustave Schmid, two architects who designed hundreds of buildings throughout the Chicago area in the 19th and 20th centuries. The Medinah Temple is part of the Moorish revival architecture movement, a style that makes the temple look more like a mosque than a Masonic lodge.

The original interior of the building had several different chambers, most notably a 4,200-seat concert hall. This interior feature has since been demolished and remodeled, but the pavilion was incredibly ornate and acoustically ideal when it stood.

Jason Kaufman, an independent scholar and author who previously taught sociology at Harvard and studied the role of secret societies and fraternal organizations, said the Shriners are not unique in the appropriation of their aesthetic. Use of an Orientalist aesthetic that incorporated commodified, often racist imagery from Asian, North African and Middle Eastern cultures was part of a wider colonial trend during the 19th century. Western fraternal organizations frequently used Eastern characteristics to connote secret wisdom and knowledge.

“As this particular order of Masons developed, it had a very ritualistic ceremonial and mysterious quality about it,” Kaufman explained. “... [Their thinking was] if we're going to form a group, we're going to have this aesthetic that embraces it. And we're going to have rites and rituals that create social solidarity amongst the members.”

In the past few decades, Shriners have taken small measures to change the way they style themselves — including calling their buildings Shrine Centers rather than temples. But they hold steadfast in how they dress, title their leadership positions and make use of Middle Eastern and North African symbolism. Jay Alfevirc, the current leader, or potentate, of the Medinah Shriners, said, “It's been our heritage, it was a fun thing.”

So the temple’s design, as visually impressive as it is, has an antiquated and misappropriated origin. But the building itself helps tell the history of Chicago through the events that took place there.

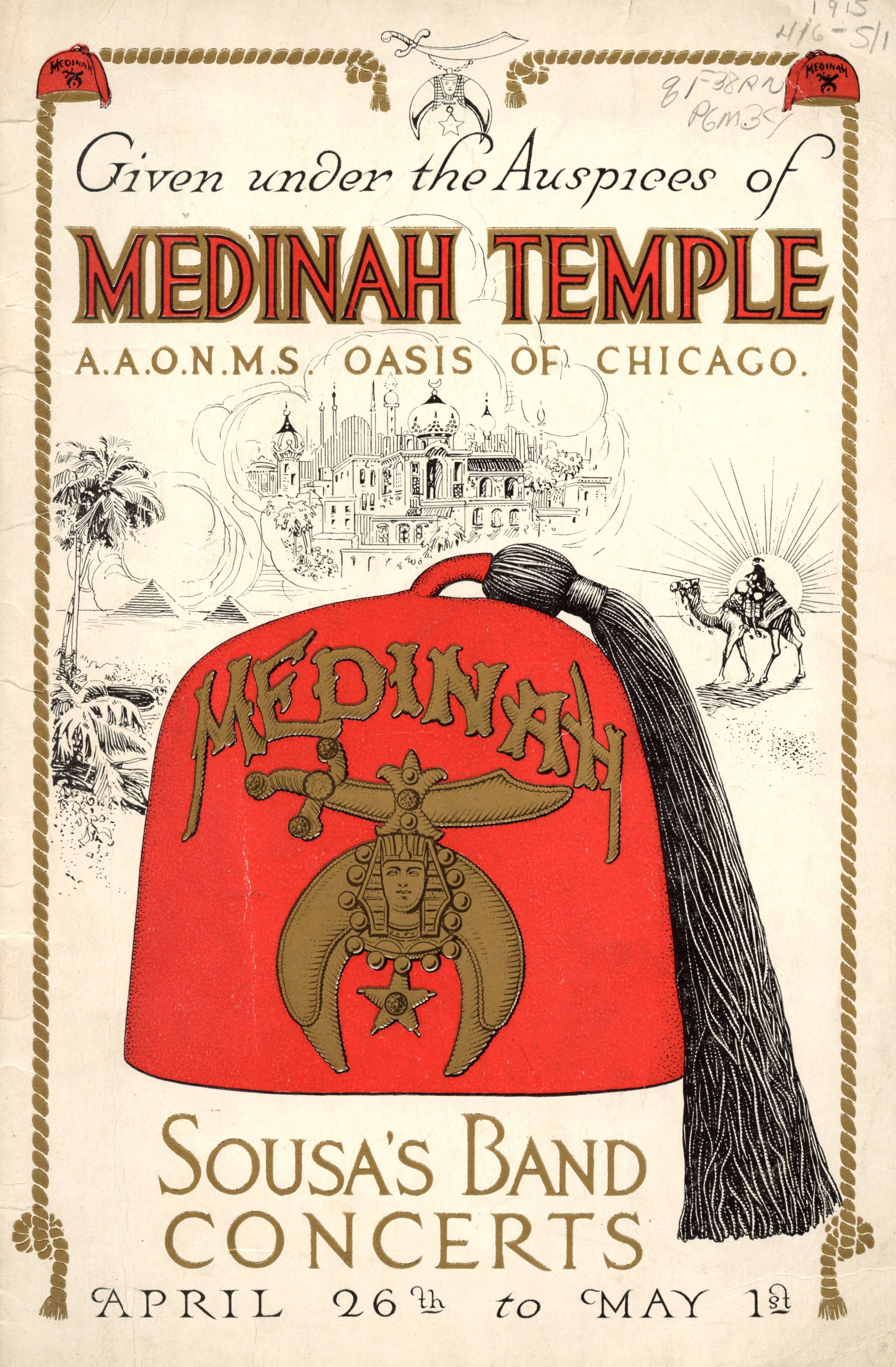

Symphonies, graduations and the Shrine Circus

The Medinah Temple hosted some of Chicago’s — and the country’s — biggest acts throughout much of the 20th century. This includes performances by Bozo the Clown and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, as well as speakers like Studs Terkel. The temple also hosted countless community events such as high school graduation ceremonies.

“The very best performances I ever saw [were] there. [The temple] used to be the recording studio for the Chicago Symphony. … And when [it] was recorded, I would sneak in and listen to that.”

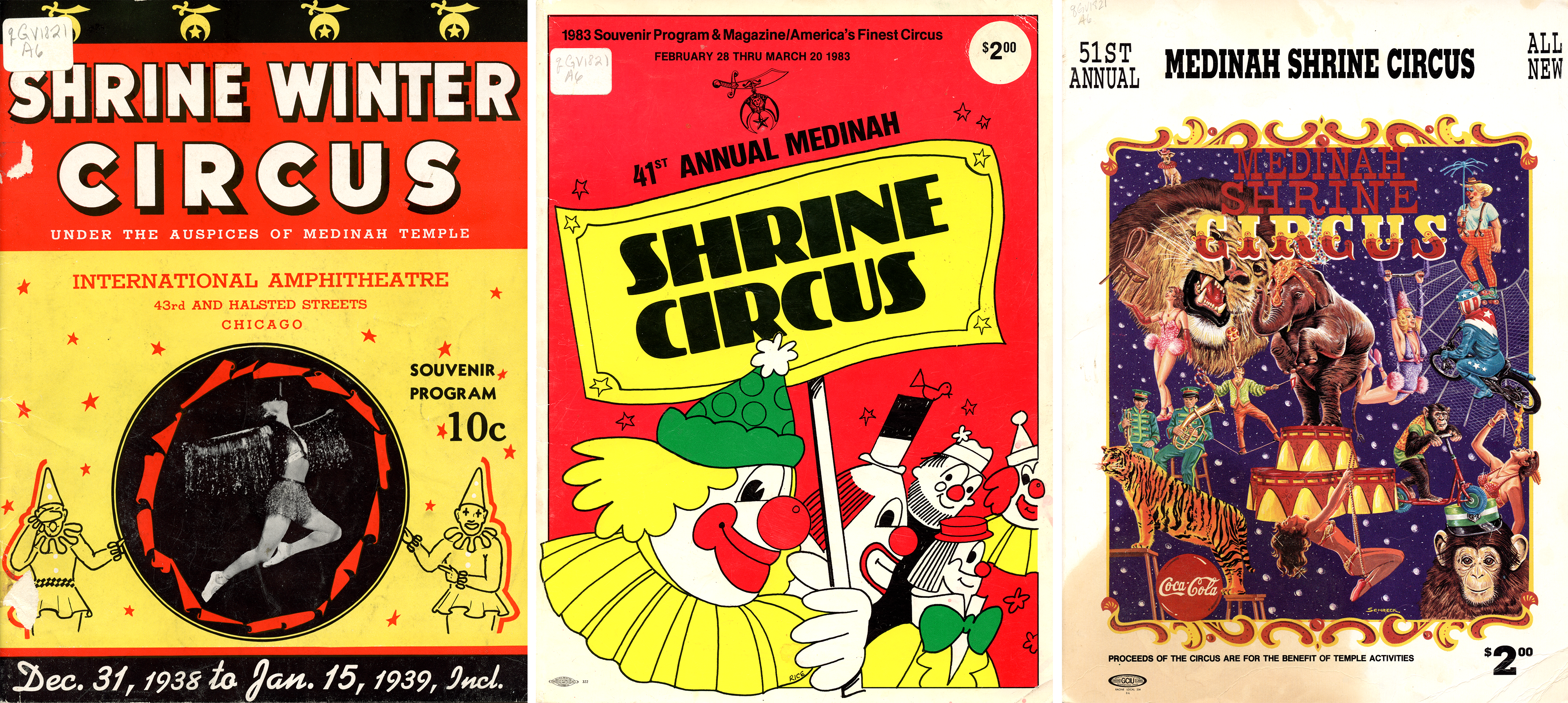

Perhaps the temple’s biggest draw was the Shrine Circus. It came to town every year for decades, and drew thousands of people from across the Chicago area.

Barber, a Medinah Shriner since 1964, said he’ll never forget the time a circus tiger got loose.

“There was [a tiger] that came on to the bandstand one day … It didn't eat anybody but was just looking around,” he said.

New types of performances often meant temporary changes to the building’s design.

“When the ice show was there, they built a rink on top of the stage,” Barber said. “I filled it with water and ran freezers into it from out on Ontario Street and Ohio Street … they'd have to run for a couple of days in order to make the ice.”

The Medinah Temple also hosted a number of well-known political, spiritual and cultural figures, including Mayor Harold Washington, the Dalai Lama and former Vice President Dick Cheney in the 1980s and ’90s.

The Shriners had a close relationship with Mayor Richard J. Daley, and made him an honorary member while he was in office.

“He was well known for being the number one Irishman in Chicago and dying the river green,” explained Jay Alfirevic of the Medinah Shriners.

Because of that, instead of the typical red fez, the Shriners presented Daley with a green fez with “Mayor of Chicago” stitched on it.

Medinah Shriners part ways with the temple

Eventually, many Shriners moved out of Chicago, and their largely suburban membership did not find the trips downtown worthwhile.

So after nearly a century of calling downtown Chicago home, the Shriners made the decision to sell the building and move to the suburbs.

The only problem was by that point, the temple had become architecturally iconic in the city. And people like Ward Miller of Preservation Chicago wanted the building officially designated with landmark status — which comes with a host of regulations around how the building’s exterior can and cannot be updated.

“All of a sudden when we decided we had to move from Medinah Temple, it got landmarked, and that made it way less attractive for buyers,” said Barber.

Regardless, the building was landmarked in 2001, and sold later that year. Its exterior is protected from significant change or demolition due to its architectural importance.

The Medinah Temple is owned by Friedman Properties, a real estate firm that has rented the building to Macy’s (which operated it as a Bloomingdale’s for 16 years) and most recently to Bally’s Corporation. The entertainment company opened a casino at the venue earlier this month. It has three floors of gaming and nearly 800 slot machines. City officials have said they have high hopes for the tax revenue the venture will bring for Chicago.

But with Bally’s scheduled to move out in a few years once the casino’s permanent location in nearby River West is completed, there is still a question of the building’s future.

“I'm hoping that in time the Medinah Temple can have a cultural and creative use,” said Miller. “And that people will be attracted to it by its architecture, by its history, by its historical and cultural legacy — more than [by its use] as a temporary casino.”

Anna Mason is a journalist and producer living in Chicago, specializing in local history and archival media. Follow Anna @annadotmason