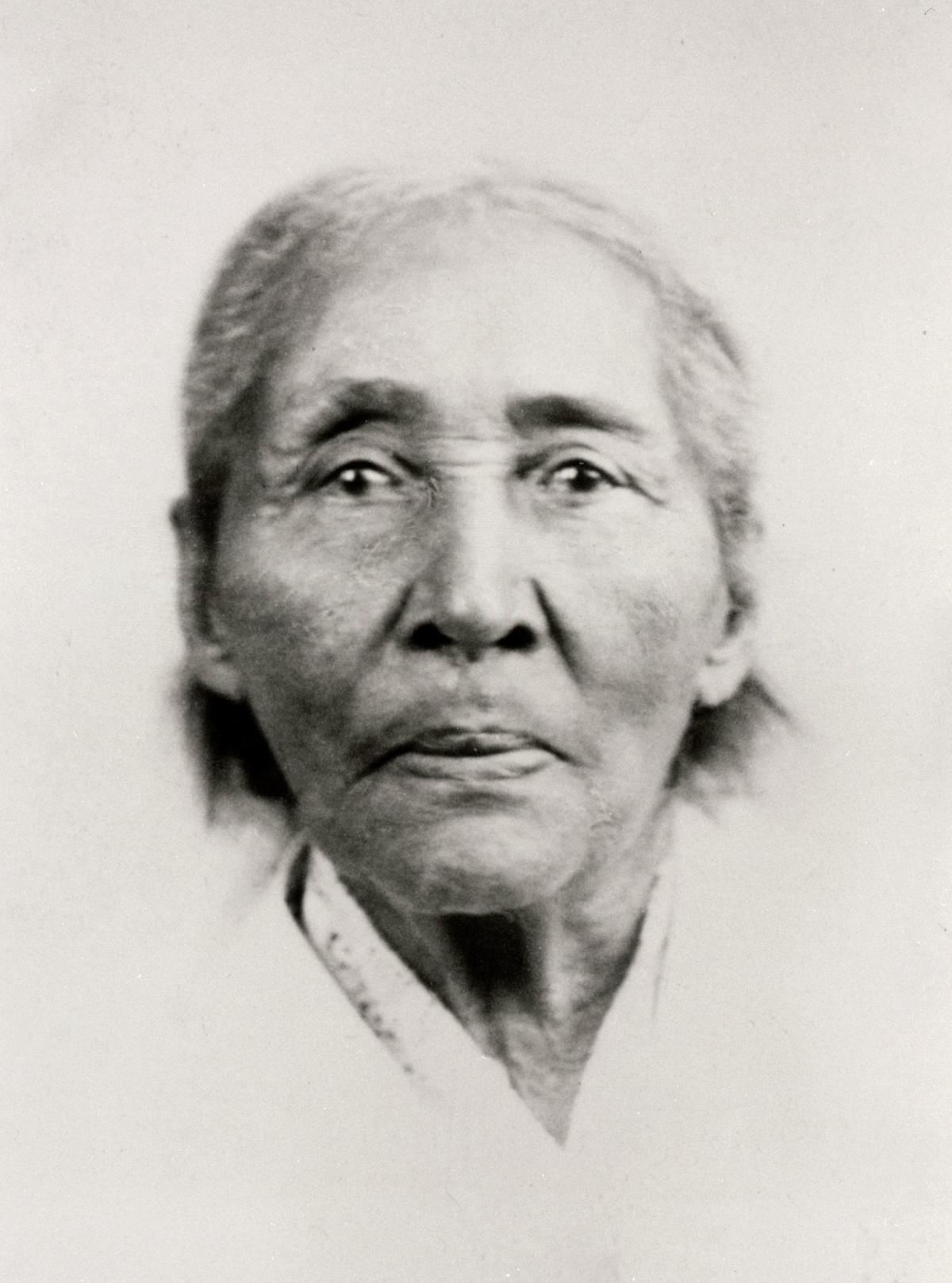

When I first saw a late 19th-century portrait of labor activist Lucy Parsons, I immediately thought she reminded me of my grandmother.

I couldn’t help but notice her striking features and defiant glare, and I felt like I could immediately recognize other Black women when I looked at that image. So, I was then both confused and disappointed when, after a quick Google search, I quickly realized that during her life Parsons didn’t publicly identify as Black. In fact, she tried to create confusion around her racial identity.

“She preferred that people speculate about her origins,” says Jacqueline Jones, professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin and author of Goddess of Anarchy: The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American Radical. “She at one point claimed that she had been born to a Mexican parent and then a Native American parent, she would get them mixed up, which was which, because this was all a fabrication.”

Parsons was so successful in raising questions about her race, that many biographies of her on the internet say she was of mixed race. This includes the one on the Chicago Park District website (there is a park in Chicago named after her) which says she was “born of a mixed Native American, African American, and possibly Hispanic heritage.”

While researching Parsons for her biography, Jones discovered that there were no records indicating that Parsons was Native American or Hispanic. She also found evidence that Parsons had tried to hide this from the public by creating an alternative story about who she was and where she came from.

Jones explains the reason Parsons lived this lie is likely because of the trauma she experienced in her early years — trauma that may have led Parsons to deny her Black ancestry and possibly affected the types of causes she took up as an activist. And, as I found out, Lucy Parsons became a woman who would defy every limitation and who never quite fit into any box people tried to put her in.

From a Virginia plantation to Texas

Lucy Parsons was born as Lucia in Virginia in 1851 to an enslaved woman named Charlotte. Her biological father was likely her enslaver, Thomas J. Taliaferro. Toward the end of the Civil War, Taliaferro moved the enslaved people on his plantation west to Texas in an arduous, monthslong trek. Once there, it’s likely that Charlotte and her family fled while Taliaferro was away on a trip.

Charlotte relocated her family to Waco, Texas, a town that seemingly had promise for freed Black people. Tera Hunter, a professor at Princeton University whose research focuses on gender, race, labor, and Southern histories, says Lucy, Charlotte, and her family would have been a part of a growing Black community.

“A significant population of African Americans [were] moving to Waco after the Civil War because of opportunities for work outside of the plantation,” Hunter says. “And what's interesting is that you do also have the rise of Black institutions like schools and churches. There's the Republican party that African Americans pretty much dominate, as they're becoming enfranchised in the South.”

But Lucia [Lucy Parsons] was not free from the expectations placed on Black women at the time. She married — possibly not legally — an older freed Black man named Oliver Benton, who was about 20 years her senior and paid for her schooling. She had a baby, likely with Benton, who died in infancy.

Soon after, she met Albert Parsons, a white newspaper editor and former Confederate soldier who’d set his sights on getting a position in the Republican party. Parsons wanted a job in politics and he likely thought it would be easy to do this as a Republican and by seeking the support of newly freed Black people who he thought would vote for him. But, when Democrats gained control of the Texas legislature in 1873, those aspirations became futile. So he set his sights on Chicago.

Albert and Lucia were able to legally marry within the small window of time in 1872 when interracial marriage was legal and they both saw Chicago as a place of opportunity — one where Albert Parsons could seek political opportunities and where Lucia could do more than what she saw as menial labor, sewing and cooking for white people. It was a place Albert had visited before with a group of newspapermen, and he was in awe of the city. On the way there, Lucia shed her name, and her past life, and became Lucy Parsons.

“She clearly wanted to escape what it meant to be a Black woman at that time,” Hunter says. “The structures that were imposed on Black women, the limitations of what they could aspire to be.”

As she becomes a public figure, Parsons’ racial identity is questioned

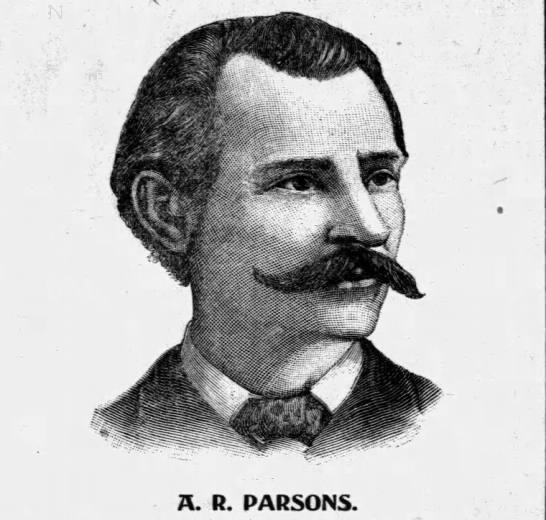

The Parsons moved to Chicago in 1873 and settled in a community of German American immigrants and quickly became involved in the socialist labor movement of the time. Albert Parsons, with his oratory skills, became a prominent face of the labor movement while Lucy Parsons worked behind the scenes on strategy.

It wasn’t until Albert Parsons was prosecuted, convicted, and executed for the Haymarket Affair that Lucy Parsons became a more prominent figure in the labor movement. On May 4, 1886, after a series of protests and strikes to demand an 8-hour workday, an unidentified person threw a bomb at police, a riot ensued, and eight people were killed as a result. Albert and Lucy Parsons were at a nearby bar when the bombing occurred, but Albert Parsons — who had spoken to a peaceful crowd earlier that day — was one of the men who was accused of a crime.

Lucy Parsons had been working in the background until then, earning money for the family with a booming business as a seamstress, but she started advocating publicly on his behalf during the trial, and that’s when she started getting attention.

“A lot of her fame revolved around the fact, yes, she was Albert Parsons' wife and then his widow,” says Jones, Parsons’ biographer. “But also on her own, she really carved out a very impressive reputation as a speaker and agitator.”

It was also the time when people started to ask questions about Lucy Parsons and the past she’d tried to leave behind. Parsons’ features and skin color made her look racially ambiguous, Jones says. Some reporters would describe her skin as a “mahogany hue” while others would say she was “a shade of copper” — with people assuming she had a “Negro” nose, had “Aztec blood,” or was a “modern Cleoptra.”

“After Haymarket, there were a lot of people who were interested in who Albert Parsons was, and there were reporters in Chicago who went back to Waco and began to ask about the two of them,” Jones says. “And that's when their pasts did catch up with them.”

Reporters went to Waco and interviewed people who knew Lucy Parsons as Lucia, including her first husband, Oliver Benton. But when the Parsons were confronted with this information, both Lucy Parsons and Albert Parsons (while in jail) denied the claims of her Black ancestry and said, again, that her mother was Mexican and her father was Indigenous. The only information Lucy Parsons provided to reporters, and she very rarely did, was that she was orphaned at 3 years old and grew up with her mother’s brother in a different part of Texas — far from Waco — and at some point, she picked up “Gonzalez” as her maiden or middle name.

After her husband’s death, Lucy Parsons continued her work with white socialists, becoming one of the most recognized voices in the labor movement and a founder of the Industrial Workers of the World, often referred to as Wobblies. And as she continued to deny being Black, her activism focused on class struggle —rather than any specific labor issues that had to do with racial injustice.

A woman of contradictions

As she rose in popularity, Lucy Parsons remained a woman of contradictions, not just based on her racial identity but also as a woman activist. Her fiery rhetoric was anything but ladylike, according to biographer Jones. It’s what led the Chicago Police Department to call her “more dangerous than 1,000 rioters.”

“She would say she would love to run the guillotine machine that cut off the heads of ‘capitalist robber barons,’” Jones says. “It was very extreme rhetoric that her followers loved. Right here was this kind of demure, fashionable lady engaging in really some really raw rhetoric about the workers’ struggle against capitalism.”

Parsons also bumped heads with other women activists of the time. Jones says she was against women’s suffrage and had very traditional views about gender roles.

“She had a very active personal life herself,” Jones explains. “And yet, she presented herself as a very prim, Victorian wife and mother (widow and mother eventually) and really challenged these other anarchists like Emma Goldman who were arguing for a much freer expression of sexuality than Lucy Parsons would ever admit to publicly.”

When it came to civil rights and issues affecting Chicago’s Black communities specifically, Parsons stayed away.

“I did find it ironic that she really delighted in this contrarian attitude in riling up her listeners, in poking the eye of the establishment and disparaging American institutions like Congress, the president, the two party system, and yet, she was in certain respects very conventional, that she focused exclusively on the white working class,” Jones says.

Even as the city’s Black population grew, Lucy Parsons, along with white radicals, ignored Black folks’ plight. They didn’t want to support them but also thought Black workers shouldn’t break strikes and go to work in these factories. And Parsons’ rejection of Black issues is likely one of the reasons why we don’t know her as well as we know other famous activists of the time.

“There was a Black community in Chicago, but her attention was focused on the white laboring classes,” Jones says. “So that makes her, again, kind of an enigma that you can't feature her in a book about civil rights heroines and heroes; [you] just can't do it because that wasn't what she did.”

A radical existence

Although Lucy Parsons didn’t easily fit in any box, her very existence was revolutionary. Hunter, the Princeton professor, says Parsons was still among a very essential generation of Black women who were writers, speakers, and organizers.

“Despite her efforts to deny her racial heritage, she is a fitting image of other Black women of her time who shared some of her political aspirations to make American society more democratic, but who were different from her in that they proudly embraced their racial identity and they fought against race-based oppression, as well as gender oppression and class oppression,” she says.

And like me, Hunter also recognizes Parsons in other powerful Black women of the time: the way she spoke up for what she believed in, the way she made her own rules, the way she pushed back on societal norms.

“The person that comes to mind immediately [that] she resembles is Ida B. Wells, the journalist and preeminent anti-lynching activist, and they even lived in Chicago during some of the same period — both were courageous, some said outrageous, outspoken women,” Hunter says. “They came from similar modest backgrounds and they both created these new pathways that seemed unimaginable for women of their time.”

I may have been upset — mostly just disappointed — when I initially learned that Lucy Parsons denied being Black. But, learning about all she went through was a gut check: Who am I to be disappointed when women like Lucy Parsons are the reason I can be who I am? She made the decisions she felt were necessary for her and really created her own world — opening up for more Black women to do the same.

Enslaved women before Lucy Parsons did not have the opportunity to define who they wanted to be. And just that defiance of breaking out of those boxes is something that led the way for me to be able to define who I want to be and what I want to do. That is what I personally will always honor Lucy Parsons for. I am grateful for her as an ancestor, and I thank her.

More about our question asker

After Donald Trump was elected president in 2016, Laura Villanueva joined the Women's March in Chicago. While there, she caught sight of a banner that said “Lucy Gonzalez Parsons” and identified her as an organizer and labor leader from the turn of the 20th century.

“And I'm like, ‘Who is that?’” Laura said. “I've heard about Jane Addams, who I think was around the same time, [but] I've never heard about [Lucy Parsons]. And she seems like she lived a full life.”

Laura is Mexican American, and she says she is sympathetic to Lucy Parsons’ reasons for claiming both Mexican and Indigenous heritage.

“Maybe she was in Texas and she's like, ‘Oh, they're treating Mexican women better than me. I'm going to say I'm Mexican, but we're coming from Texas. This is going to be our new life,’” she said. “I mean, it sucks that she couldn’t live in a world where she could identify as a Black woman.”

Arionne Nettles is a journalism lecturer at Northwestern University’s Medill School. Follow her @arionnenettles.

This episode was produced by Jesse Dukes and edited by Alexandra Salomon.