What happens if the water in Lake Michigan keeps disappearing?

By Lewis Wallace

What happens if the water in Lake Michigan keeps disappearing?

By Lewis WallaceJust how bad are low water levels in Lake Michigan? Well, consider this holiday tale.

Each December in Two Rivers, Wisconsin, a guy in a Santa suit sets out to deliver a boat load of Christmas trees to nearby Manitowoc. But this year, Santa Claus almost didn’t make it out of town.

“Santa Claus had to get on top of the boat because he couldn’t get inside the boat, cause it was too low so they had to put him on the roof,” says Michael LeClair, the white-haired owner of Susie Q’s, the town’s main commercial fishery.

“He could walk right off the top of the dock right onto the top of the boat, that’s how low the water is…25 trees in the boat and he was sitting on top of the pilot house,” LeClair added. “That’s how he got on and off. It’s just a problem for everything and everyone.”

And it seems to be a problem nearly everywhere along Lake Michigan.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reported water levels in Lakes Michigan and Huron hit record lows in December, at nearly two and a half feet below average. Army Corps projections for lake levels have been dire since September, when it became clear that a relatively warm, dry fall and winter would not provide relief from a long drought and one of the the hottest summers ever.

Now the water is an inch below its record low for this time of year in 1964, and continues to drop. Shippers, fishermen, and small-town tourist harbors say federal help with digging out channels and repairing infrastructure could keep the low water problem from becoming a crisis.

At Michael LeClair’s sizeable fishing operation, he says the low water has started to hurt his business. Behind the Susie Q’s smokehouse, LeClair keeps stacks of large gray plastic bins his fishermen have to lower down from the dock with ropes, fill with smelt, and lift back up.

“All we can do is wait. Hope things change.”

Great Lakes, shrinking harbors

“All you have to do is go up and down the coast lines and see it,” said Chuck May of the Great Lakes Small Harbors Coalition. “You see boats that haven’t been able to get out yet this year, we’ve got on this lake we’ve got a pontoon boat sitting at the end of its 200 foot or so dock setting on bare dry land, there isn’t any water within at least 30 feet of the boat.”

May retired to Portage Lake in the small Michigan town of Onekama. When the water dropped nearly a foot from the previous year’s levels, May saw parts of the lake turn into mud flats. In Onekama, as in countless other harbors, the water is so low that wooden pilings are exposed and deteriorating and boats can no longer get in and out of the harbor.

But for years now, the federal government has held back much of the money in the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund, which brings in about $1.5 billion a year. May accuses politicians of trying to make a dent in the deficit at the expense of smaller federal harbors like Portage Lake; a tiny fraction of the $750 million in unused funds could solve the city’s problems.

In order to get around the funding dry-up, Great Lakes harbors have routinely sought out earmarks and special appropriations to stay operational. The frugal fiscal cliff environment in Washington is unfavorable to that approach these days. The Army Corps’ detailed list of necessary repairs seems to have an urgent project budgeted for nearly every single Great Lakes harbor, and the vast majority of the projects are unfunded for FY2013. This year only 15 out of 140 federal harbors in the Great Lakes will get dredged.

May founded the Great Lakes Small Harbors Coalition in 2007 to try to pass federal legislation that would require the government to spend all the money in the fund on its harbors. That legislation, known as the RAMP Act, is creeping its way through congressional committees and could come to a vote this year.

The heart of Two Rivers

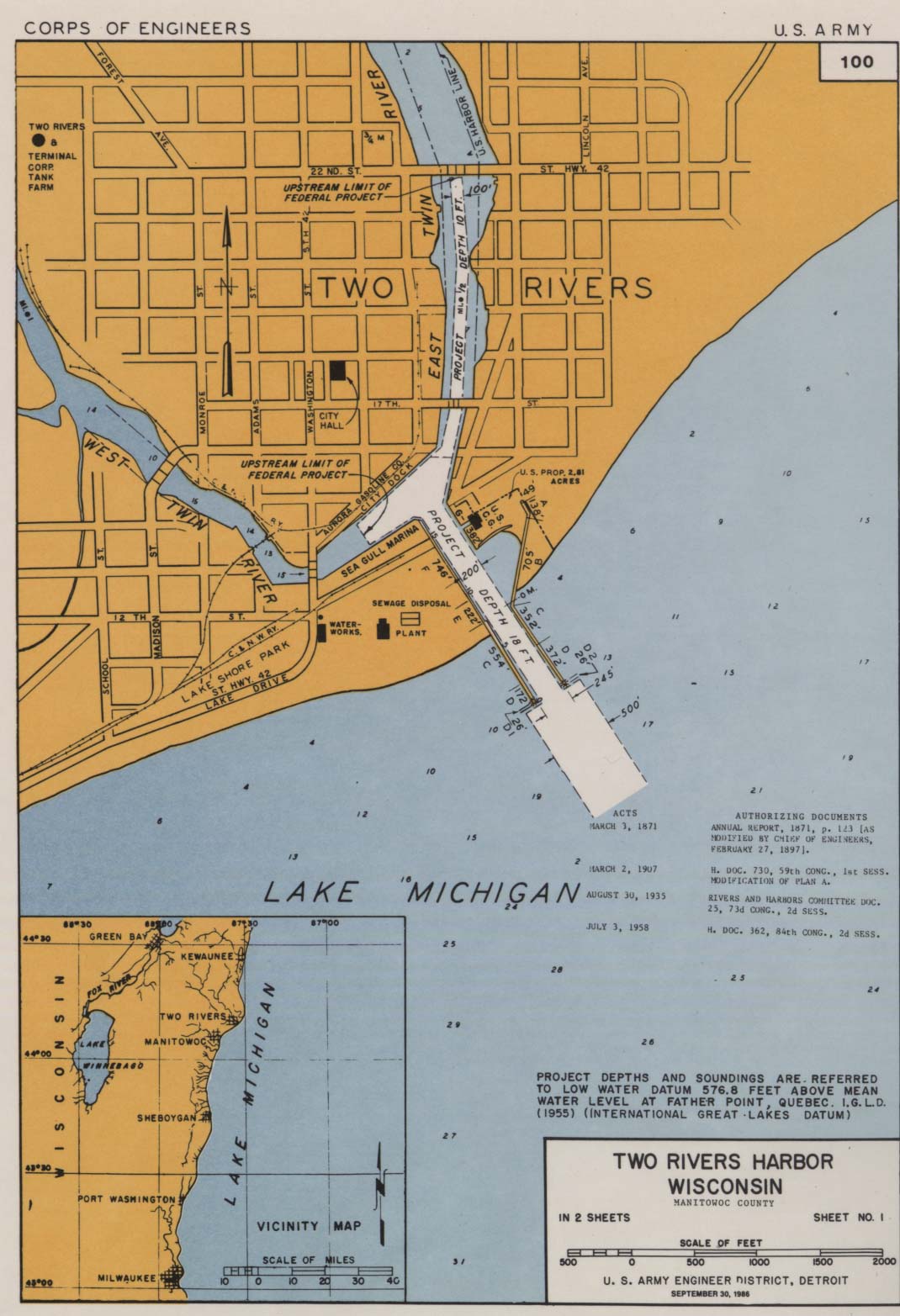

Back across the lake in Two Rivers, Wis., City Manager Greg Buckley agrees that the need for federal help in small harbors is dire. A wide federal channel is the center of Two Rivers, and it hasn’t been dredged for decades.

“There are areas where there’s only two feet of water,” said Buckley, standing at the meeting point of the city’s two rivers looking out onto the channel. Right now in a kind of DIY-dredging larger fishing boats use their propellers to pick up sand and silt as they go. If the water gets much lower, they could hit rock.

The town of Two Rivers needs its waterways. From the channel’s meeting point with Lake Michigan, a massive brick factory stretches all the way back through town on the riverfront - and it’s almost completely empty. The Hamilton factory opened in the 1800s to make wood type, and later made kitchen appliances and office furniture.

“Our community band was the Hamilton band, our city hall is the reuse of the Hamilton community school,” said Buckley. “It’s eerily quiet now.” The operations of the former Hamilton company, which were bought and sold by various larger companies over the years, have been leaving incrementally for nearly two decades. The last manufacturing jobs associated with Hamilton moved to Mexico in 2011.

“We’ll pick ourselves up from that, something good will ultimately come from it,” said Buckley “and a lot of that relates to the water resources we sit right on top of, assuming we still have water in the lake and water in the rivers.”

Buckley envisions Two Rivers as a tourist destination, with beautiful beaches and quaint harbors to complement the blue collar fishing town. He wants to redevelop the Hamilton building and turn Two Rivers’ beaches and boating opportunities into a draw for potential homeowners. He checks out Illinois license plates when they come through town, hopeful that wealthy Chicagoans will look to Two Rivers for summer homes.

The trouble with dredging

Dredging, or digging up sand and silt from the bottoms of rivers to keep them at set depths, is how the federal government has maintained its waterways since the 1800s. But it’s also part of the reason why Lake Michigan is particularly low these days. Scientists agree that routine dredging of the St. Clair River, which connects Lake Huron to Lake Erie via Lake St. Clair, has permanently lowered average levels in Michigan-Huron by a full foot. Dredging solves immediate problems for shipping, but it does not return water to the lake.

And dredging can have immediate environmental consequences, too. In an industrial place like Indiana Harbor at the southern tip of Lake Michigan, the actual material dredged up is toxic and has to be carefully stored.

Indiana’s not immune

Back down in Indiana Harbor, managers for huge shipping operations agree with the small harbor leaders that the federal government should release all the harbor maintenance funds to the Army Corps to fix up the harbors.

“If we had another summer like we had this summer, you know, lord help us,” said Dan Cornellie of ArcelorMittal steel.

For every inch of water the lake loses, the ships supplying two large steel plants here have to lighten their loads by hundreds of tons. Right now freighters are coming into the harbor with two and a half feet less draft than just a few years ago, so for every six trips a ship makes, ArcelorMittal pays for a seventh to make up the difference. The result is a pricier bottom line for the thin, high-quality steel used to make everything from refrigerators to coffee machines.

Cornellie has been in the industry for a long time, and he remembers the low lake levels of 1964, but he said this time it doesn’t feel the same.

“Well, in ‘64 nobody talked about climate change,” he said. “There’s no mystery what’s going on. It’s a question of whether any of those temperature or precipitation trends reverse.”

A future in drought?

2012 was just tallied as the hottest year on record, and U.S. climatologists predict a continued rise in average temperatures in coming years. Precipitation in the Michigan-Huron basin in 2012 was at 87 percent of its long-term average. Although the drought is expected to let up near Lake Michigan, parts of the Midwest will likely stay in severe drought conditions into the coming summer. The Mississippi River is currently barely holding off a shipping shut-down as it nears its own record low south of St. Louis.

The water will likely go back up in spring and summer, as it does every year; late winter is generally the lowest time in the lakes’ yearly cycle. But another summer of extreme heat or drought, and this winter’s woes will seem like kid stuff.

“Maybe we can’t just glibly talk about hey the lakes go up and down and hey what are you gonna do, give it a few years it’ll be back,” said Buckley, back up in Two Rivers. “We’re not keeping up with the infrastructure needs now, if you exacerbate that situation with dropping lake levels, the economic impact long term could be pretty profound. Now whether that’s climate change, whether that’s the fact that we humans have just sat here and observed these things for 150 years and think that’s the norm when maybe it isn’t, well, I don’t know.”