What’s That Building? Cardinal Meyer Center

The site used to be a hospital for Civil War soldiers and was funded partly by the sale of the original copy of the Emancipation Proclamation.

By Dennis RodkinThere are two monumental structures that catch your eye at 35th and South Lake Park. One is the curving suspension bridge for bikes and pedestrians, its central pylon 120 feet tall. The other is the tomb and 96-foot tall monument to Stephen Douglas, the U.S. Senator from Illinois who opposed Abraham Lincoln in a famous series of debates over the spread of slavery in the United States.

With those two soaring above, it’s easy to miss a building on the southeast corner that has a significant historical distinction: The money to build it came in part from the sale of Abraham Lincoln’s original, handwritten version of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Now an office building owned by the Catholic Archdiocese and called the Cardinal Meyer Center, the building has several additions to the original 1864 structure, which was a hospital and rest home for Civil War soldiers. That part is on the northeast corner of the blocklong building, the four-story part you see first if crossing the pedestrian/bike bridge from the east. The T-shaped part there is four stories high, its arched windows hooded and its roof supported by carved brackets.

This was the Soldiers’ Home, designed by William W. Boyington, who also did the Chicago Water Tower and Pumping Station, the Joliet Prison, the old Illinois State Capitol, the Iowa Governor’s mansion and many other noteworthy buildings. Funds to build the Soldiers’ Home were raised by the Great Northwest Sanitary Fair in 1863. At the time, “sanitary commissions” were something like the Red Cross — civilian volunteer groups providing health care and other support to Civil War soldiers.

In Chicago, the sanitary fair was organized by two women, Mary Livermore and Jane Hoge. The two women met while taking care of Union soldiers in 1861 at Camp Douglas, which was adjacent to this site and later became a POW camp for Confederate soldiers. Livermore and Hoge visited military hospitals in southern Illinois and Kentucky, and in 1863 launched the idea of a sanitary fair to raise $25,000 to build a sanitary home for returning soldiers.

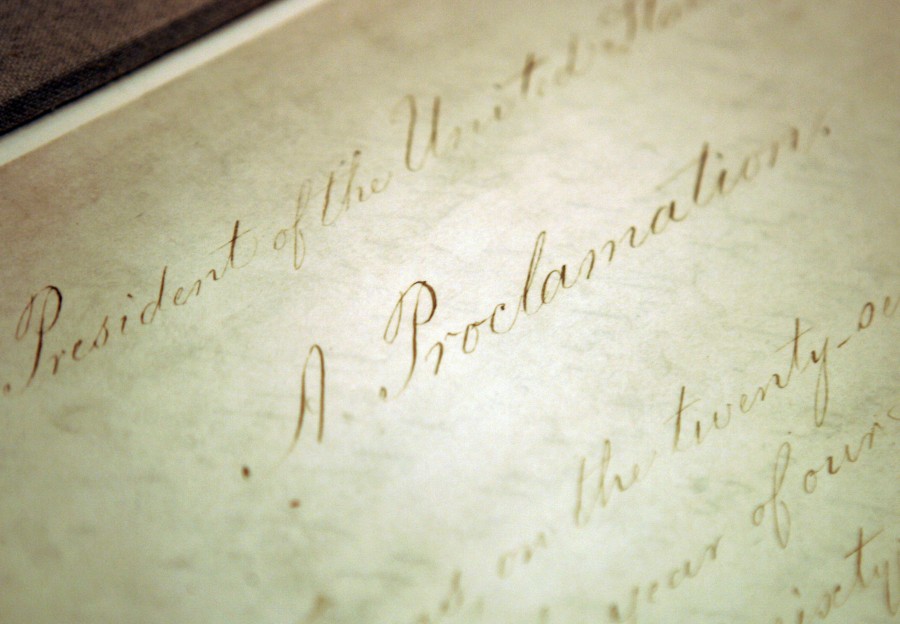

They had an audacious idea. On Jan. 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, in which he declared all enslaved people in the Confederate states “are and henceforward shall be free.”

Ten months later, Mary Livermore wrote to Lincoln to ask for a donation to the fair.

“The most acceptable donation you could possibly make,” she wrote, “would be the original manuscript of the proclamation of emancipation.” Rep. Isaac Arnold, a Chicago congressman and one of Lincoln’s strongest supporters in Congress, seconded the idea.

Lincoln agreed and sent his handwritten copy of this already-historic document. In the letter he sent along with the document, Lincoln wrote, “I had some desire to retain the paper, but if it shall contribute to the relief or comfort of the soldiers, that will be better.”

Hoge and Livermore wrote back to Lincoln to thank him, and described the Emancipation Proclamation as “the star of hope, the rainbow of promise, that has risen above the din and carnage of this unholy rebellion, and will fill the brightest page in the history of our struggle for national existence.”

Thomas Bryan, president of the sanitary fair, bought the Lincoln document in November 1863 for $3,000. Everyone who gave $1 or more to the fair received an engraved copy of the Lincoln donation, and there may have been as many as 7,000 distributed, which is why some historical articles say the Emancipation Proclamation sold for $10,000, not $3,000. Overall, the fair that had been intended to raise $25,000 raised more than $86,000. A second fair the next year raised another $83,000.

The Soldiers’ Home was built starting in 1864 and funded with the proceeds of the two fairs. The Emancipation Proclamation hung on a wall of the Soldiers’ Home until 1868. That year, the Chicago Historical Society opened a new building at Ontario and Dearborn, and the Soldiers’ Home gave the society the Emancipation Proclamation to display there. That would turn out to be the wrong choice.

The document was put in a big frame and hung on the wall of the historical society’s reception room. The Great Chicago Fire started Oct. 8, and in the predawn hours of Oct. 9, a curator of the historical society’s collection, Samuel Stone, was one of the people trying to save its collection. He was attempting to break the Emancipation Proclamation’s heavy frame that was bolted to the wall, but was overcome by smoke and had to leave the building.

Lincoln’s handwritten Emancipation Proclamation was destroyed in the fire.

The tragic irony of that, historical society director Paul Angle wrote in the Chicago Tribune in 1948, is that the Soldiers’ Home, where the Emancipation Proclamation hung until 1868, was not touched by the 1871 fire.

“Thus, the managers of this Soldiers’ Home, seeking to preserve a great state paper for posterity, succeeded only in bringing about its destruction,” Angle wrote.

In 1872, the Soldiers’ Home was sold to a Catholic order of nuns for use as an orphanage because their original building burned down in the Great Chicago Fire. The Sisters of St. Joseph Carondelet used the former Soldiers’ Home, and additions that were made throughout the 1950s, first as an orphanage and later as a school for special needs children. They were there from 1872 until 2005.

Now, the Archdiocese of Chicago uses it as offices. The entire interior has been gut-rehabbed in the 21st century, church officials said, and there are no historical details intact inside.

Dennis Rodkin is the residential real estate reporter for Crain’s Chicago Business and Reset’s “What’s That Building?” contributor. Follow him @Dennis_Rodkin.

K’Von Jackson is the freelance photojournalist for Reset’s “What’s That Building?” Follow him @true_chicago.