Lots of Chicago-area buildings make you stop and ask: “What’s that building?” WBEZ’s Reset is collecting the stories behind them! You can also find them on this map.

The first gay rights organization in America formed right here in Chicago's Old Town neighborhood -- decades before the Mattachine Society in 1950s Los Angeles or the 1968 Stonewall uprising in New York City’s Greenwich Village.

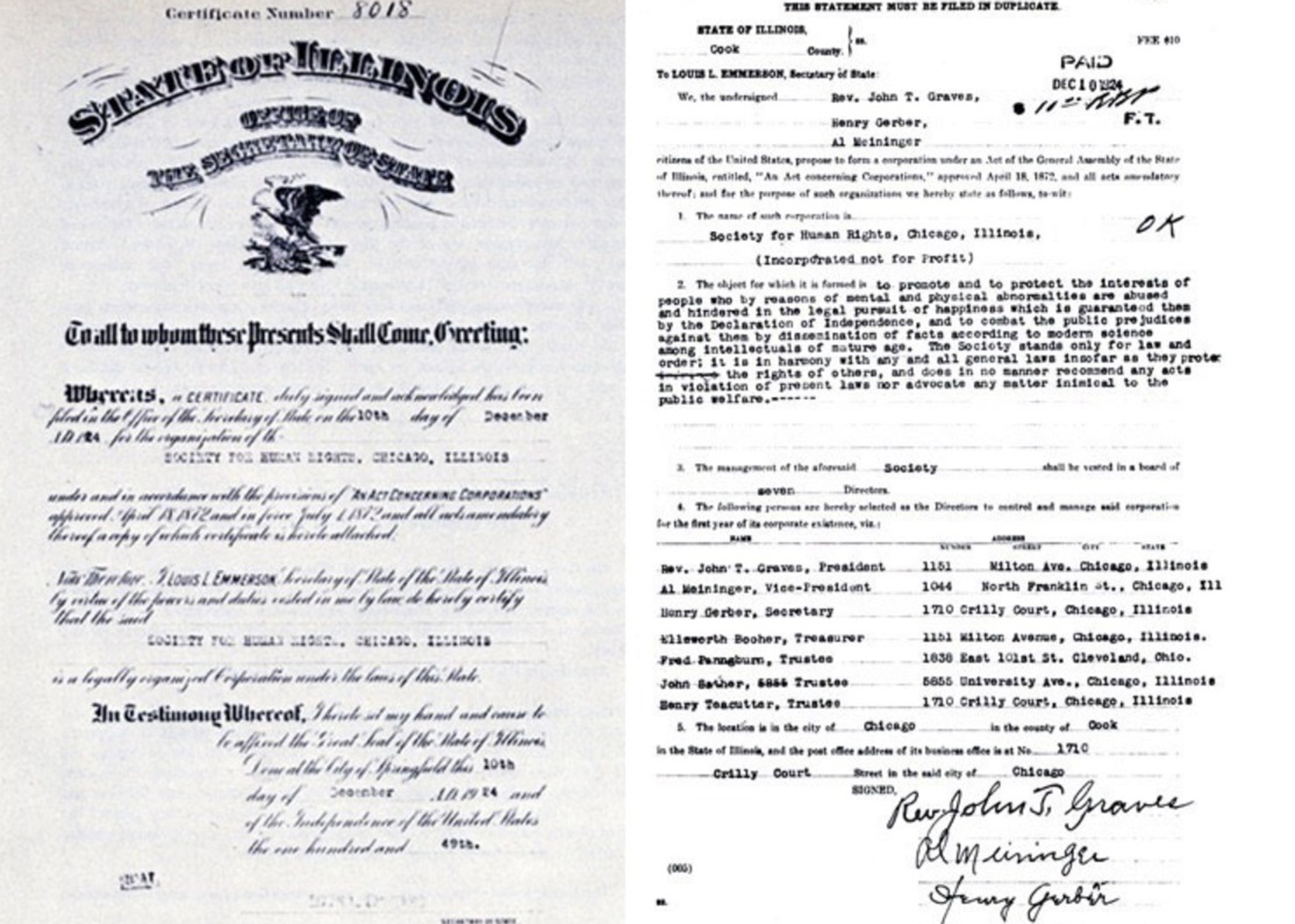

Organized in 1924, the Society for Human Rights lasted less than a year, harassed out of existence by a police raid and lawsuits.

But its origins are in a limestone row house at 1710 N. Crilly Court. In the 1920s, it was a boarding house, where founder and secretary of the Society, Henry Gerber, and the group’s trustee, Henry Teacutter, rented rooms. Today it’s been made into a single-family home.

There were seven names listed in the Society’s founding documents. Two of the seven men lived nearby on Milton (today Cleveland) Avenue; another was on Franklin Street near Moody Bible Institute. A sixth man listed his address as a church in Hyde Park, and the seventh lived in Cleveland, Ohio.

When the group applied for a state charter, they stated their purpose was to: “Promote and to protect the interests of people who by reasons of mental and physical abnormalities are abused and hindered in the legal pursuit of happiness.”

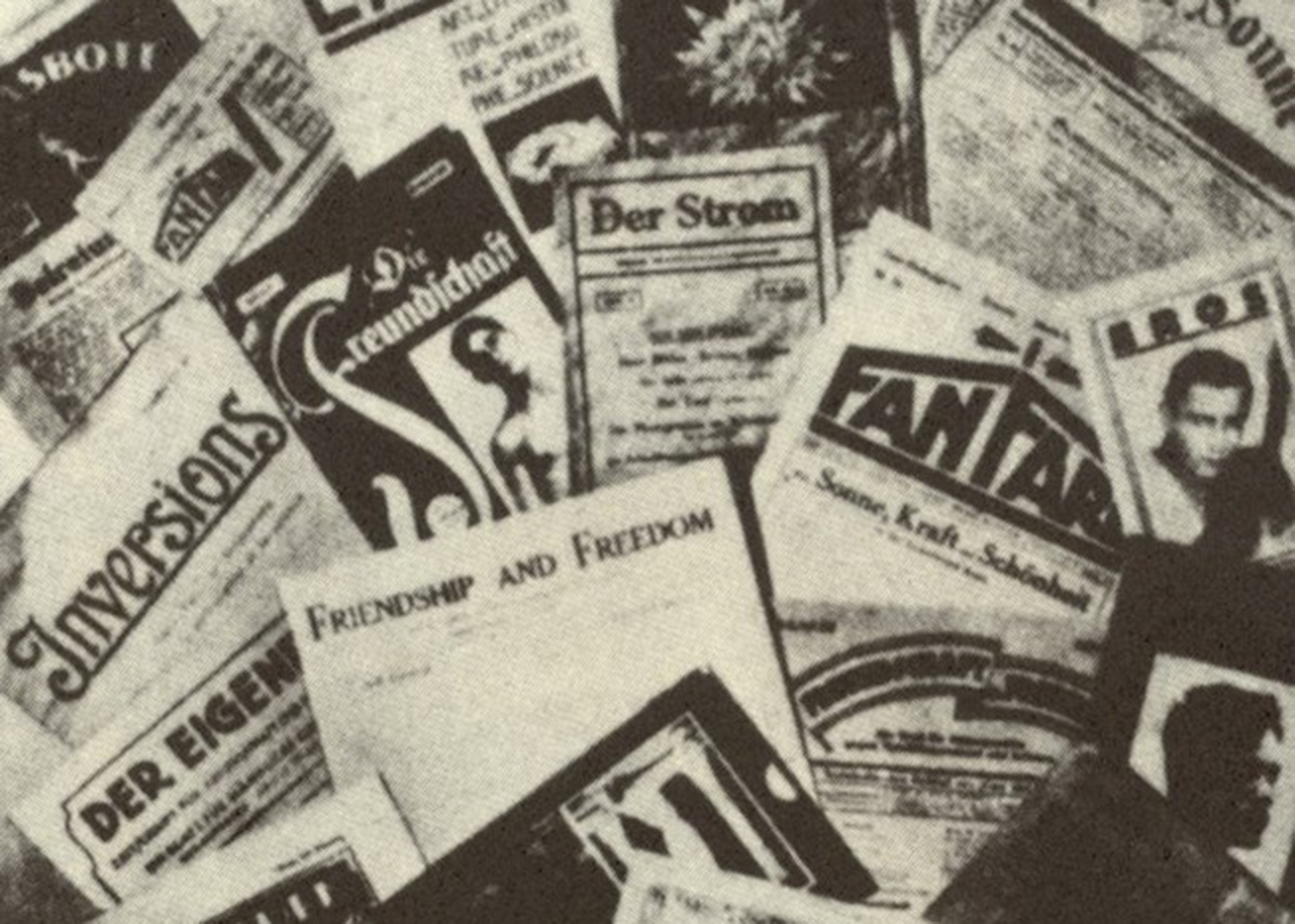

There was no mention of the words gay or homosexual, and the Society received nonprofit status. The group’s efforts included a newsletter called Friendship and Freedom, which only lasted two issues.

The wife of one of the men later described her husband’s bisexuality to a social worker, who went to the police, according to the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame. Gerber and others were arrested in a police raid.

Police presented a powder puff they’d found in Gerber’s apartment as evidence and a sentence where he wrote, “I love Karl.” But the “Karl” was Karl Marx, and the sentence was from a book review, according to Shirley Baugher, who bought the Gerber home with her husband Norman in 1985.

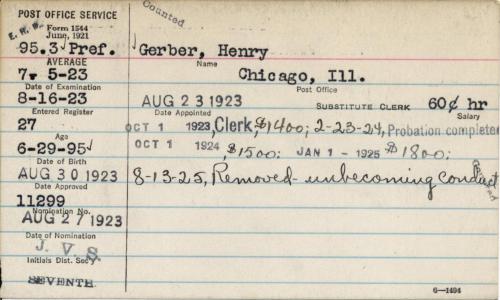

The case was ultimately dismissed, but Gerber was fired from his post office job for “conduct unbecoming.” He moved to New York City in 1927 and joined the U.S. Army for his third time.

The memory of the short-lived Society for Human Rights was all but forgotten.

Then, in 1962, 37 years after the Society for Human Rights was forced to shut down, Gerber wrote a letter to the gay rights publication ONE detailing the short history of the Society for Human Rights.

Prior to forming the group, Gerber had served in the Army in Germany, where homosexuality was more accepted. He wrote, “I had always bitterly felt the injustice with which my own American society accused the homosexual of ‘immoral acts.’ I hated this society which allowed the majority, frequently corrupt itself, to prosecute those who deviated from the established norms in sexual matters.”

Gerber’s letter -- where he wrote passionately about the group’s studious efforts to reform Illinois laws that criminalized homosexuality -- is now a kind of founding document of the movement to secure the right to love. He died in 1972.

Baugher wrote a Chicago Now blog entry in 2014 where she described the trial. The couple didn’t find out their home’s history until more than a decade after they bought it. They completely renovated the interior, so the basement room where the Society held meetings and the Gerber and Teacutter’s upstairs rooms look nothing like they did in the 1920s. The Baughers declined to let WBEZ come inside.

“I’m delighted,” Baugher said of the home’s history. “I’m sorry they were not able to be more successful in the enterprise. I’m sorry they were literally chased away. But as far as advocating for the group of people, I’m very pleased they were here.”

In 2015, the house was declared a national landmark.

“The National Park Service is America's storyteller, and it is important that we tell a complete story of the people and events responsible for building this great nation,” U.S. Interior Secretary Sally Jewell said in the announcement. “As we honor the pioneering work of Henry Gerber and the pivotal role this home played in expanding and fighting for equality for all Americans, we help ensure that the quest for LGBT civil rights will be told and remembered for generations to come."

Dennis Rodkin is a real estate reporter for Crain’s Chicago Business and Reset’s “What’s That Building?” contributor.