On a June evening in 1933, Florence Price enthralled Chicago. An excited audience packed the 4,000-seat Auditorium Theater to hear Chicago’s Symphony Orchestra perform Price’s

.

She became the first Black woman to have a symphony performed by a major American orchestra.

Florence Price’s music and life are becoming more widely known, but that hasn’t always been the case. Curious City recently got a request from Shari Ebert, who’d performed a Price symphony with her local orchestra. The music made Ebert want to know more about this woman and the breadth and impact of her work.

So back to that June evening.

The concert was an event for the Chicago World’s Fair – A Century of Progress. Its theme of invention and innovation had inspired the CSO’s music director Frederick Stock to look for music that reflected a new American experience. He knew Price’s music as the year before, she’d won a prestigious music honor for Black composers called the Wanamaker award. Her classical scores were influenced by African and Black American music, including spirituals.

When the Chicago Symphony Orchestra completed its performance, the audience, made up of both Black and white Chicagoans, roared in applause, giving Price and her work ovation after ovation.

Price, then 46 and dressed in a long flowing white gown, was called back to the stage again and again as the applause continued. The Chicago Daily News reported that there hadn’t been a response that huge since the 1880s. The Chicago Defender said the performance was culturally significant and that it showed "the Race is making progress in music."

A sophisticated upbringing

Florence Beatrice Smith was born in 1887, a decade after the end of Reconstruction, to a middle-class family in Little Rock, Arkansas.

In the tight-knit Black community, little Florence was a child prodigy. At four, she had her first piano performance. At 11, she published her first composition. At 14, she graduated from high school.

She had a list of career accomplishments before marrying Thomas Price, an accomplished lawyer, in 1912. She moved from Atlanta, where she had worked as the head of the music department at Clark College (now Clark Atlanta University) back to Little Rock. The couple had two children, and like her mother, Florence Price balanced motherhood with teaching music.

But in 1927, a series of changes pushed the Prices to join the many Black families moving north. They chose Chicago. Violence against Black people was increasing; the Prices feared for their family’s safety. And Thomas Price’s once-profitable law practice had started to decline.

The Chicago Black Renaissance

In Chicago, the family moved into a home on 38th and Calumet in the city’s Black Belt, later called Bronzeville. It was a vibrant neighborhood, bustling with people. The graystones that lined many blocks were overcrowded, filled with multiple families and boarders. But this concentration of people made the community tight in other ways. It was exploding with Black energy and culture.

Barbara Wright-Pryor, a retired concert singer, professor and music critic, is with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s African American Network. She said Chicago’s Black musicians welcomed Price.

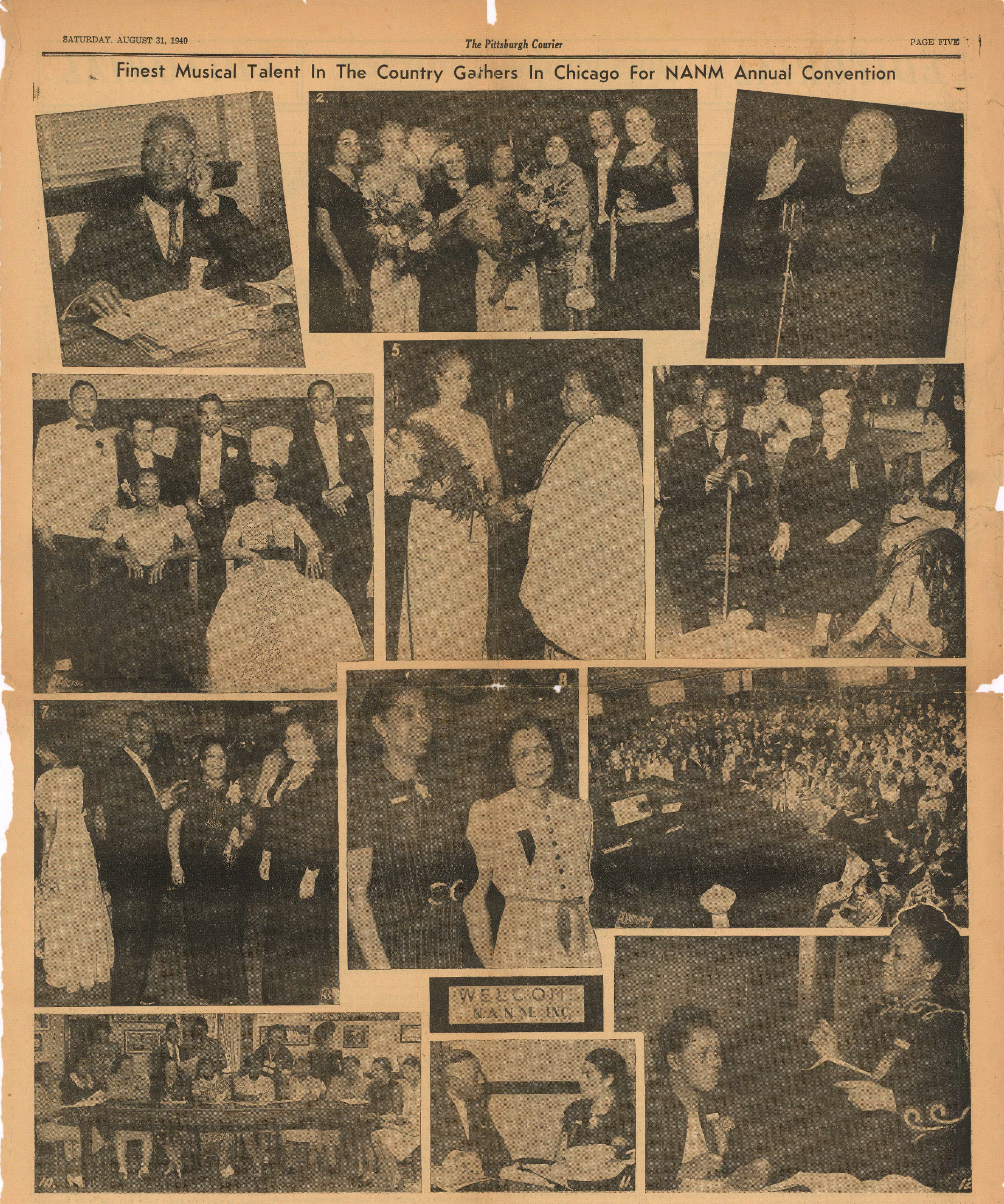

“When she arrived in Chicago, it was the Black Renaissance actually going on — all types of music and art were being performed and exhibited throughout,” Wright-Pryor told Curious City. “She met with a multiplicity of Black musicians here in the city.”

Black writers, artists and musicians gathered to share ideas and inspiration at places like the Hall Library on 48th and Michigan, drawing Black people of all disciplines, and even visitors stopping through the city.

Like its more well-known predecessor in Harlem, Chicago’s Black Renaissance became one of the most culturally significant periods in American history. And Florence Price, along with her classical music counterparts are a huge part of this legacy.

Struggle and success

Even classically trained Black musicians like Price were not always welcome in white mainstream classical spaces. She was often rejected by conductors around the country to whom she mailed her compositions, in hopes they’d play her music. As she once wrote in a letter to a conductor: “To begin with I have two handicaps — those of sex and race.”

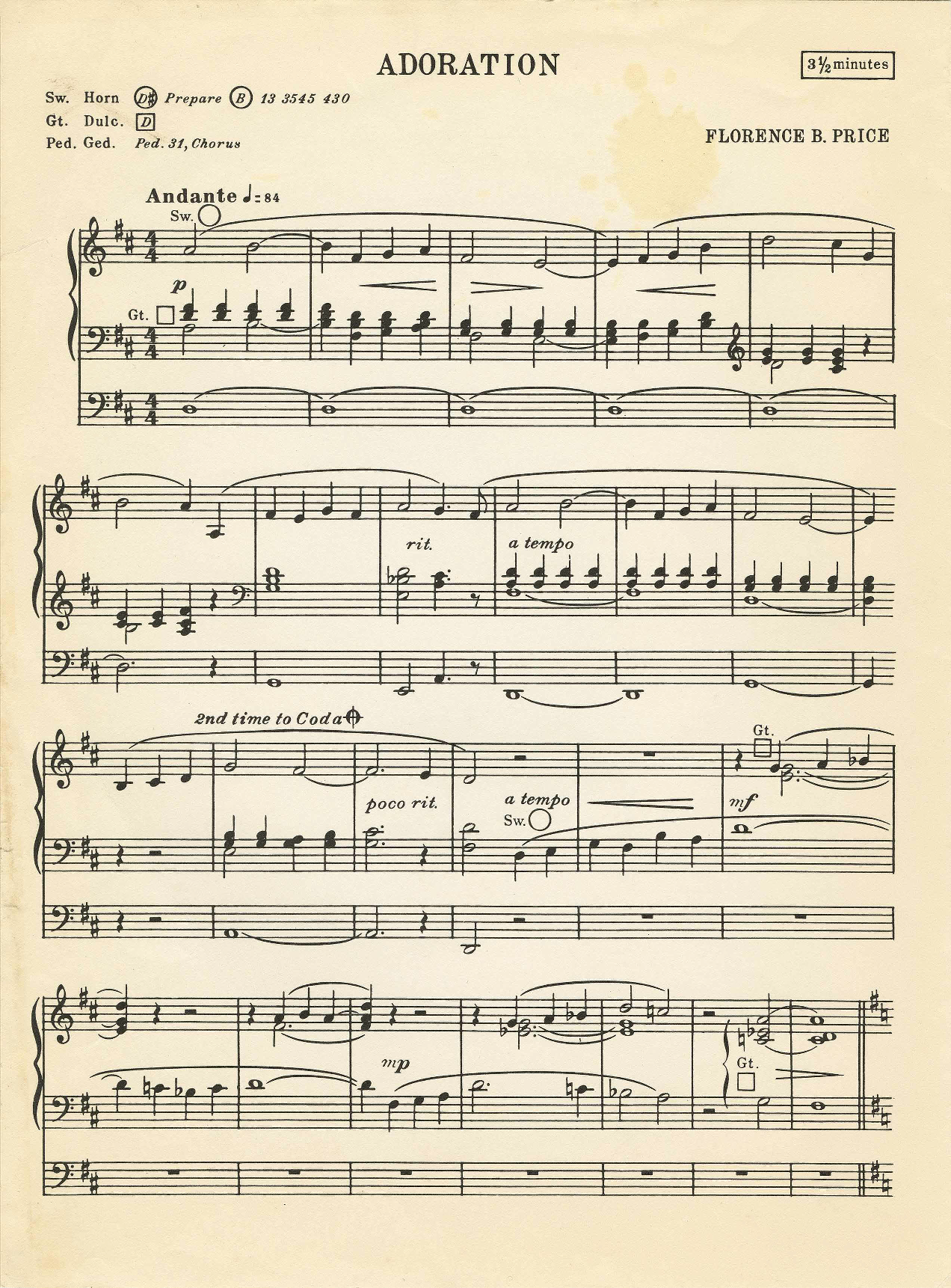

“Because of the segregation problems, they could not get employment in the music industry,” Wright-Pryor said. “So many of them became church musicians, organists, pianists, conductors. Some actually went into jazz, some worked at the … United States Post Office at night and then performed their careers during the weekends at churches.”

Price’s community extended past her work, enveloping her when, in 1930, she filed for divorce from her husband. According to The Heart of a Woman, a biography about Price’s life by Rae Linda Brown, Thomas Price was physically abusing his wife and a judge granted her a divorce on the grounds of “extreme and repeated cruelty.”

Price had to make money to care for her daughters, who were nine and 14. So she played piano and organ in churches and in silent film theaters up and down the Stroll — the stretch of State Street between 26th and 39th streets.

But Price wasn’t on her own in rebuilding her personal life.

Price had befriended fellow pianist Estella Bonds through the city’s Black music organizations. Bonds, a pillar of the community, often took in friends who needed help. She invited Price and her daughters to live at her large three-story home. And soon after, Price became a teacher and mentor to her daughter Margaret Bonds.

Margaret Bonds often entered and won musical competitions along with her mentor. In 1932, when Price’s symphony won the Wanamaker award, Bonds also won for a song. The night the CSO performed Price’s symphony at the World’s Fair, Bonds became the first Black instrumentalist to appear with them.

Under Price’s tutelage, Bonds would go on to become one of the greatest composers of the Chicago Black Renaissance.

A genre of its own

Florence Price and Margaret Bonds are now two of the names people mention most often when talking about Black classical music from this period. But they weren’t alone in this work — that’s something many experts emphasize.

“I'll use Florence Price’s words or phrase: melting pot,” Ege said. “She said something along the lines of, ‘I believe a music very American and very beautiful, can come from the melting pot, just like the nation itself has done.’”

That melting pot is present in the works of other Black composers who were active in the 1930s through the 1950s — especially Black women composers.

Ege said Black women remained the foundation of this creative community: women like Price and Bonds, along with other musicians — including singer Nora Holt, composer Irene Britton Smith, and pianist/composer Betty Jackson King.

“In this era, we hear the influence of the spirituals, we hear the influence of blues, and jazz, and we also hear the influence of these women's classical music training,” Ege said. “So we hear, well, we hear symphonies, we hear sonatas, we hear all of these classical inspirations, and it really is

.”

Legacy

Florence Price lived in Chicago until her death in 1953. Then, in 2009, a couple renovating an abandoned house near Kankakee was surprised when they found pages and pages of Price’s handwritten music and notes.

After the discovery, it took experts a decade to sift through and organize those papers. Scholars such as Rae Linda Brown and Barbara Garvey Jackson worked to turn them into scores that could be played and recorded. And now, as more of Price’s music is available, her life and legacy are becoming better known.

Douglas Shadle, associate professor of musicology at Vanderbilt University’s Blair School of Music, said people are drawn to both Price’s music and her story. Each time her music is performed anywhere in the world, it gets an instant standing ovation, he said.

“It's the kind of story that I think is all too rare in classical music, where we see the composers as these hidden figures occupying secretive spaces,” Shadle said. “And certainly, the act of composition is very difficult and it can seem superhuman. But we have to remember that these people are human, they have human needs, human struggles, human joys, and encountering a composer and her music that we also encounter as a person, I think makes it all the more meaningful.”

Karen Walwyn is a concert pianist, composer, and a scholar of Florence Price’s music. She said the music is intentional: It pays homage to her experience as a Black American, often leaning into music of Black dance and celebratory traditions.

“A lot of the dances were back in the motherland that were used to celebrate the ends of wars, to honor the kings, to bring in new births, weddings, etc., and these rhythms traveled across the seas,” Walwyn said.

Notably, Price’s work includes dances like the Juba, which started in West Africa and traveled with enslaved people to the Americas, and the Cakewalk, which began in the mid-19th century and was performed on plantations.

“The poignancy of this is that she's sharing and telling the story of her ancestry and combining it with European models: the structure, the way harmonies are treated and developed,” Walwyn said. “And what a beautiful way to bring the history to us in such an artful and audibly beautiful way.”

Lara Downes, a pianist and a scholar of unknown American voices in classical music, said it was the emotion in Price’s first

, which is based on the spiritual “Sinner Please Don't Let This Harvest Pass,” that drew her in.

“It was the first time that I'd heard a piece of classical virtuoso — a sort of post-romantic piece of music that's based on a melody from a spiritual,” Downes said. “I played that piece for years, and just, you know, everywhere I went, it would cause this incredible reaction that was … very much like my own, just this emotional connection with audiences.”

Hearing her life story today, it can be tempting to assume — because she did not receive many mainstream opportunities after the CSO performance — that Florence Price’s career was not successful.

Downes encourages us to dismiss that thinking.

“I think it's a mistake to think that because she wasn't having her music played by every great American orchestra during her lifetime that she felt failure or she felt disappointment,” Downes said. “We know that she loved doing what she was doing. She never stopped, she never stopped writing music.”

Want to hear more? We recommend these recordings:

- Chicago Symphony Orchestra Music Director Riccardo Muti conducts Florence Price’s Andante moderato

- Samantha Ege’s Fantasie Nègre: The Piano Music of Florence Price

- Karen Walwyn’s Florence B. Price

- Lara Downes performs Florence Price and Margaret Bonds during an NPR Tiny Desk (Home) Concert

Arionne Nettles is a lecturer and director of audio journalism programming at Northwestern University’s Medill School. Follow her @arionnenettles.