Today, New York City is seen as the backdrop of Spike Lee’s most famous films, Atlanta is known for Tyler Perry Studios, and Ava Duvernay’s ARRAY is based in Los Angeles. But it was on Chicago’s South Side where the start of Black cinema took root.

Even before the first wave of the Great Migration in the 1910s, Chicago’s Black population had already been steadily rising. And like with other industries, Black Chicagoans found their way into film.

During the early 1900s, as silent film production was growing, Black film companies lined State Street in what would eventually be considered Bronzeville — the first of which was Foster Photoplay Company, owned by William Foster. Foster Photoplay is considered to be the first Black-owned film production company in the U.S. that featured an all-Black cast.

But unfortunately, Foster’s films and those of most of his contemporaries have been lost. (Although the exact number of how many silent films have been lost is unknown, it’s estimated that only about 25% of all feature-length silent films made in the U.S. have survived. But for “race films” — those created for Black audiences — around 80% have been lost and it’s likely that number could be even higher.)

“Black history is so many times lost, forgotten, thrown away,” said Sergio Mims, a film critic and co-founder of the Black Harvest Film Festival. “[Black silent films were] not preserved, and so, no, we don't know a lot about William Foster or the other filmmakers.”

But William Foster was a writer, using the pen name Juli Jones, and so even without his films, his writing and the work of the filmmakers he influenced helps unwrap the origins of Black cinema in Chicago — and the legacy it leaves behind.

Foster Photoplay’s ambitious launch

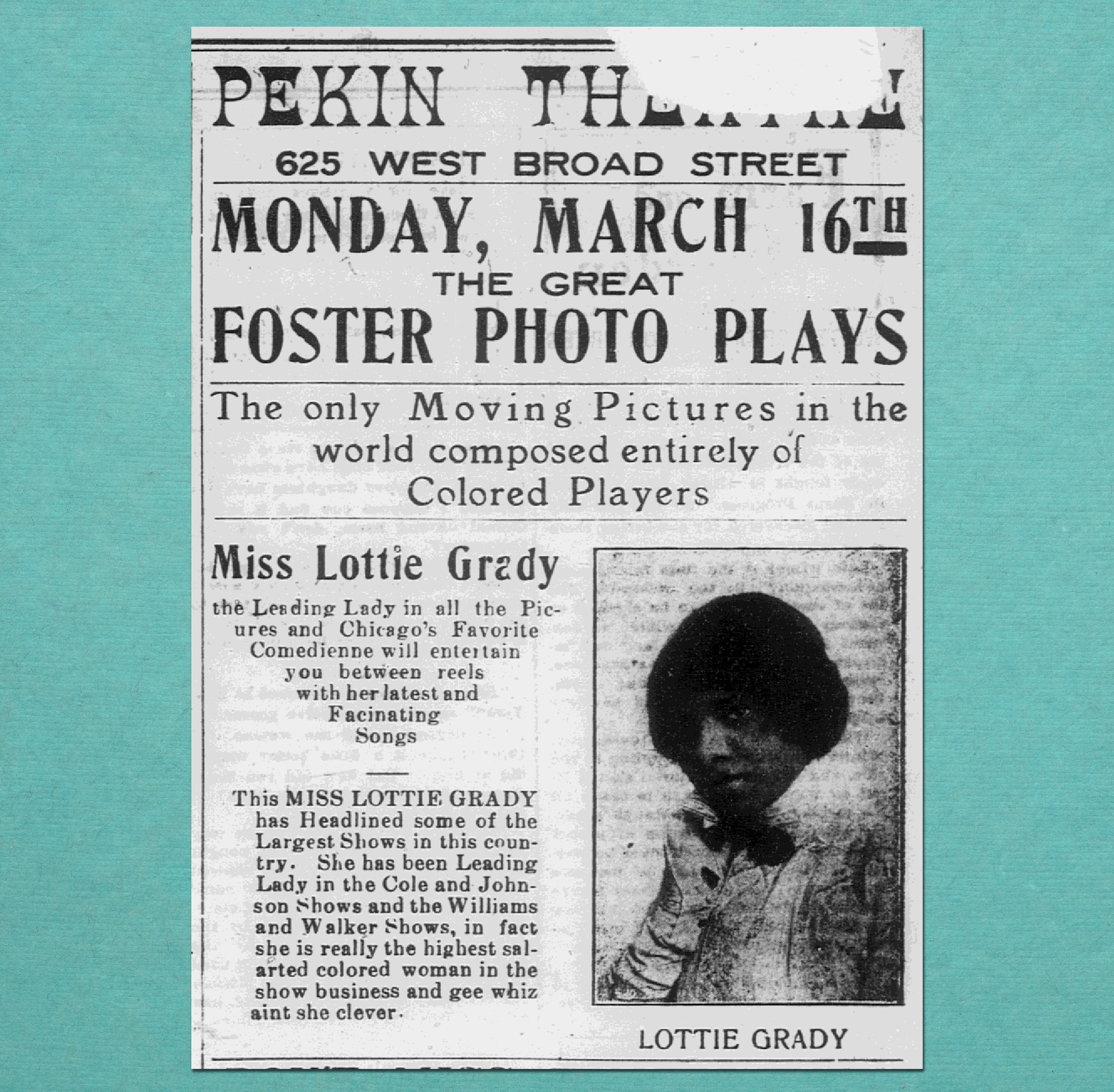

In 1913, Black Chicagoans would have lined up early to get a good seat at the Pekin Theatre. Located on 27th and State Street, it was Chicago’s first Black-owned theater and large enough to hold up to 1,200 people.

Pekin was a popular attraction because Black audiences could watch Black talent perform musicals and comedies, especially Vaudeville — a popular type of comedy that was similar to a variety show. Pekin is thought to be the country’s first Black-owned theater to have a stock company, a troupe of actors that perform regularly.

But on this particular day, the audience wasn’t there to see a live performance. They’d come to see Foster’s first silent film, The Railroad Porter. A short comedy, the film tells the story of a Pullman porter whose wife is being wooed by a cafe waiter and is credited as being the world's first film with an entirely Black cast and director. Music accompanied the film as it was projected on the screen, and one of the stars of the movie, Lottie Grady, sang live between reels.

The Railroad Porter was also screened at the States Theater on 31st and State Street, and would later be shown at the Grand Theater on 35th and State.

University of Chicago professor Allyson Nadia Field, author of Uplift Cinema: The Emergence of African American Film & The Possibility of Black Modernity, said in addition to featuring performers from the Pekin Theatre’s stock company, Foster’s film also featured other Black Chicagoans, including prominent business owners audiences would recognize from their neighborhoods on the South Side. One such actor was actually the owner of the cafe where much of the film takes place.

“The cafe waiter — who’s this fashionably dressed guy who woos the porter's wife — he's played by Edgar Lillison, who was in fact the proprietor of the popular Elite Cafe,” Field said. “So there were all these kind of ‘in’ jokes for Black audiences at the time, who would be watching these films and recognizing these figures that they see every night.”

The Chicago Defender later said singer Lottie Grady, who played the porter’s wife, was “a howling success” as “the leading lady for the Foster Film Company.” The paper also praised Foster himself, saying, “Mr. Foster is to be congratulated and every encouragement given [to] him. It is always gratifying to see a member of our race embark into a new field of endeavor.”

Even as a comedy, Foster’s film meant more to Black audiences than just entertainment. It was a depiction of the modern life that Black people were building in Chicago: owning businesses, working the extremely coveted job of being a Pullman porter, and creating these Black prosperous spaces.

“It's sort of this slapstick comedy, but it's interesting because it really showcased the new professions and modern life that were open to Black people at the time,” Field said. “The hero's the Pullman porter.”

Challenging stereotypes

We don’t know very much about William Foster’s early life. But through his writings we know what his ambitions were: to take advantage of a burgeoning film industry, to create wealth through entertainment, and to counteract the negative and untrue depictions of Black people that were the norm in white, mainstream films.

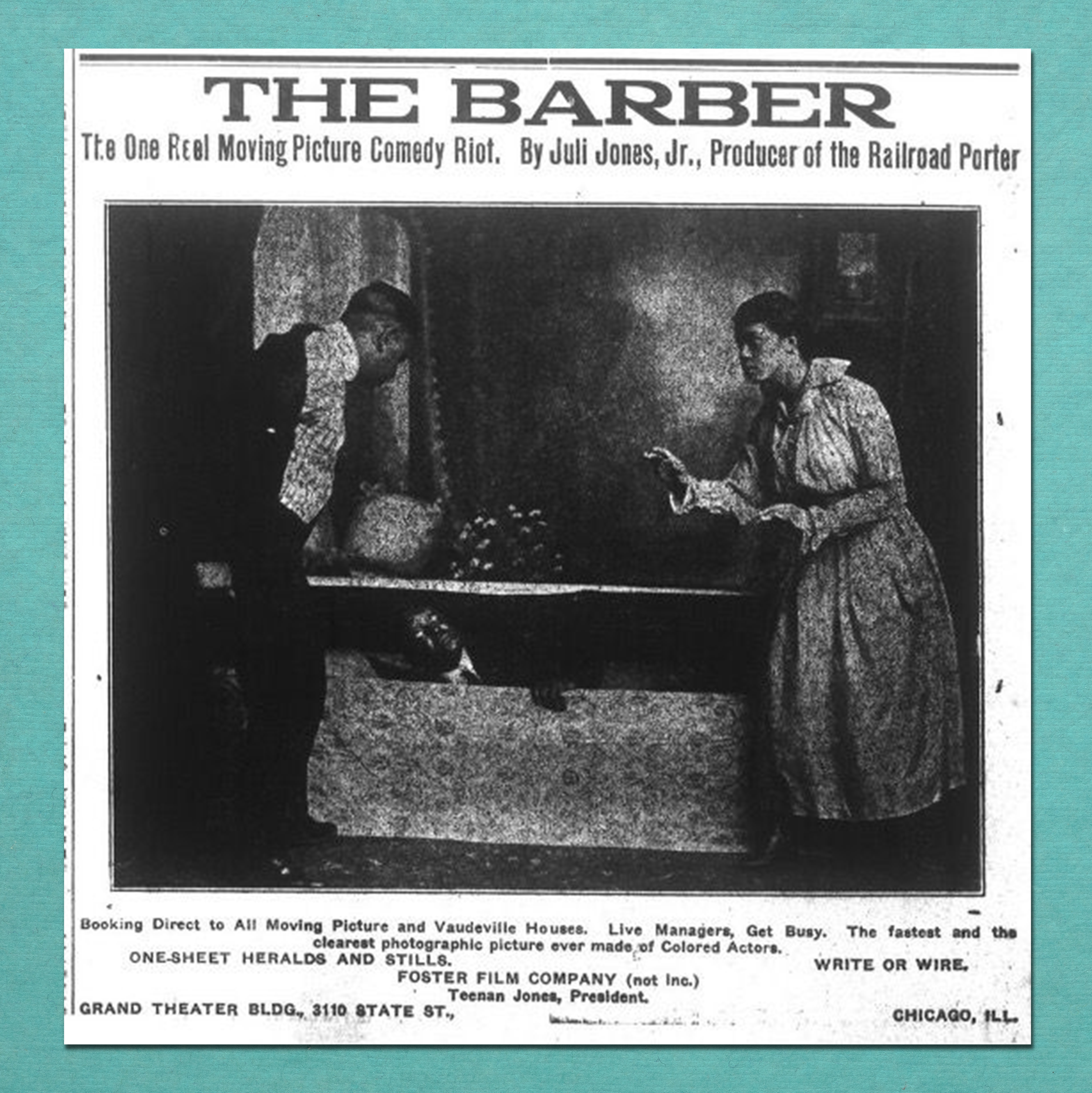

“In The Railroad Porter, in films like The Butler, The Barber, [Foster is] depicting kind of a new wage-earning, cosmopolitan Black middle class that's reflected in the audiences that these films were targeting,” Field said.

Foster wrote about what he hoped to achieve through filmmaking in a piece he wrote in response to the 1915 silent film Birth of a Nation by D.W. Griffith. Still referred to as “the most racist movie ever made,” the film had white people in blackface portraying Black Americans as unintelligent and dangerous. The film, which was extremely popular, became the first feature film to be screened at the White House.

In his article, titled “Moving Pictures Offer the Greatest Opportunity to the American Negro in History of the Race from Every Point of View,” Foster argued against what Birth of a Nation displayed on-screen. Instead, he wrote, through movies, Black filmmakers could “offset so many insults to the race” and “tell their side of the birth of this great nation.”

And Foster saw the potential profitability of movies as an industry for Black people. Looking at music as an example, he believed Black people could come together and popularize Black films across the world. He encouraged this, writing, “there are … three hundred thousand people in America working in the moving picture business in some way. Either making them or displaying them and not a thousand colored.”

Before he opened Foster Photoplay, Foster had gained valuable experience as a manager and publicist of entertainers such as comedic duo Bert Williams and George Walker and as the business manager at Pekin Theatre. So he likely wanted to seize the opportunity to join Chicago’s growing film industry, which already included many white filmmakers.

“I think what people don't realize is just how central Chicago was to the early film industry; a lot was happening right here,” Field said. “This was one of the hubs — New York and Chicago — before folks moved west and really founded Hollywood in Los Angeles, because of climate and a lot of other factors. Chicago is one of the main places in the turn of the century and into the teens.”

Foster's films became an important addition to Chicago's place as a central location for film in the U.S. But they also did something else. Films like The Railroad Porter were monumental because they directly countered the visuals of Black people that were prevalent in films made by white directors at the time.

Mark Reid, University of Florida professor and author of Redefining Black Film, said the common movie themes of the time all came from the same stereotypes.

“It comes out of always creating Black males as passive, Black females as angry matriarchs, who have no sense of love, there's no sense of love between a Black male and a Black female. It's not only that, it's also the image that Black people have this desire for white flesh.”

Long before D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, movies like Ten Pickaninnies in 1904 and The Wooing and Wedding of a Coon in 1905 portrayed Black people in the same dehumanizing depictions.

“D.W. Griffith just took that from literature that was already available on the stage and vaudeville and [the] southern writers who were doing this,” Reid said. “But even in Europe, there were these types of images and so they were borrowing from an international depiction of Black people.”

With all of these negative stereotypes, many of the emerging Black filmmakers like Foster wanted to specifically represent the Black middle class, to show that Black people were smart and respectable.

But even though Foster was known for this type of depiction in The Railroad Porter and other films, Reid says Foster also didn’t shy away from showcasing Black folks of all socio-economic levels. And in showing all types of Black people who make up a community, he also included people who might’ve been involved in illegal activity but who were — and still are — a large part of the wide range of everyday Black experiences.

“Sometimes the more exciting part of the Black community is the community outside of the law,” Reid said. “There were very famous Black gangsters in Chicago, that even though they were gangsters and they dealt in crime, they helped the Black community, just like gangsters in Harlem helped the Black community.”

Foster tries to grow his company

For years, Foster screened his films in Chicago at the Pekin, States, and Grand theaters. He also traveled out of town, showing films not just at traditional theaters but also in churches and social clubs where he would provide the projector, projectionists and ads for the showings. He also looked into expanding his production into other states.

But unfortunately, even after some years in business and with popular films in its arsenal, Foster Photoplay was never able to truly be profitable. Foster couldn’t find stable investors and wasn’t able to translate the popularity of his films in Black communities into a business model that worked for him. He tried everything from renting and selling off equipment to seeking financial support from both white and Black businessmen in Chicago.

Eventually, though, he returned to writing as Juli Jones, produced newsreels, and managed the Grand Theater until he moved to Hollywood in 1929. There he became a director for a white-owned company. With his films in hand, he’d hoped to use the experience to learn how to make talkies — or films with sound — and create another company. But he died in 1940 before he had the chance.

Foster’s work paves the way for other Black filmmakers

It wasn’t until the late 1920s with talkies, movies with sound, that Black filmmakers were able to really find longevity in the industry — but it was because of the foundation that Foster helped create. There was now a Black film industry with Black audiences ready to watch more movies that represented them.

Oscar Micheaux took advantage of that. He made his first silent film in 1919, six years after William Foster’s The Railroad Porter, and was the only Black filmmaker from the silent era to transition into talkies.

Born in 1884, Micheaux worked in Chicago’s stockyards and steel mills and also as a Pullman Porter before becoming the most famous director of race films in the silent era.

Micheaux released his first film, The Homesteader, in 1919. And although Foster made the first film produced and directed by a Black filmmaker with a Black cast, Micheaux’s film was the first race film that was long enough to be considered a feature.

Unlike Foster’s comedies, Micheaux was known for producing films of a different genre — action. In 1920, he made his own response to Birth of a Nation, an anti-lynching film called Within Our Gates. And in 1931, Micheaux released his first talkie, The Exile, the first full-length sound feature with a Black cast. In total, Micheaux wrote, produced, directed, and distributed over 40 films between 1919 and 1948.

We can trace the influence of these early Black filmmakers, like Foster and Micheaux, to contemporary filmmakers such as Spike Lee, who has called Micheaux “the grandfather of African American cinema.”

But even as more and more Black filmmakers make their mark, expanding the breadth of Black representation on film, Mims of Black Harvest offers up an important contextual reminder: “When you talk about independent Black cinema,” he said, “the very beginning, it comes to Chicago.”

About our questioner

Joyce Miller-Bean is a storyteller and retired English professor at DePaul University, who — in a previous Curious City episode — shared her family’s experience of racism and discrimination when visiting Marshall Field’s in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

When we recently asked listeners in a voting round if we should look into Chicago’s silent film history as one of our next stories, she offered up an important reminder: Don’t forget to include the African American film companies that were also active in Chicago at the time. Because like many of us, not long ago, Joyce didn’t know that there were Black film companies in Chicago in those early days of cinema.

She says she was upset that the work of these pioneering Black men and women has gone virtually missing from mainstream recognition. Even when these contributions are significant, they have been overshadowed.

“This has made me a combination of angry and hurt,” she said. “So I'm angry that this rich, marvelous chapter of cinema history that enriches everyone, it was totally pretty much excluded.”

She hopes that when people see this story, that they feel how she felt when she first read the obituary of Herb Jeffries: surprised but then encouraged to learn more about Black people’s contribution to the film industry. That, she says, is how we all can see the full picture.

“Because it's the whole rich, wonderful chapter that is not just for African Americans like us,” she said. “It's for all people to know.”

Want to learn more? We recommend these books and academic articles about Black silent film:

Boyd, Todd, editor. “Early African American Pioneers in Independent Cinema,” African Americans and Popular Culture, ABC-CLIO, 2008 Corcoran, Michael, and Bernstein, Arnie. Hollywood on Lake Michigan: 100+ Years of Chicago and the Movies, Chicago Review Press, 2013 Field, Allyson Nadia. “The Ambitions of William Foster: Entrepreneurial Filmmaking at the Limits of Uplift Cinema,” Early Race Filmmaking in America, 2016 Field, Allyson Nadia. Uplift Cinema, Duke University Press, 2015 Reid, Mark A. Redefining Black Film, University of California Press, 1993 Stewart, Jacqueline Najuma. Migrating to the Movies: Cinema and Black Urban Modernity, University of California Press, 2005

Arionne Nettles is a Chicago journalist and lecturer at Northwestern University’s Medill School. Follow her @arionnenettles.