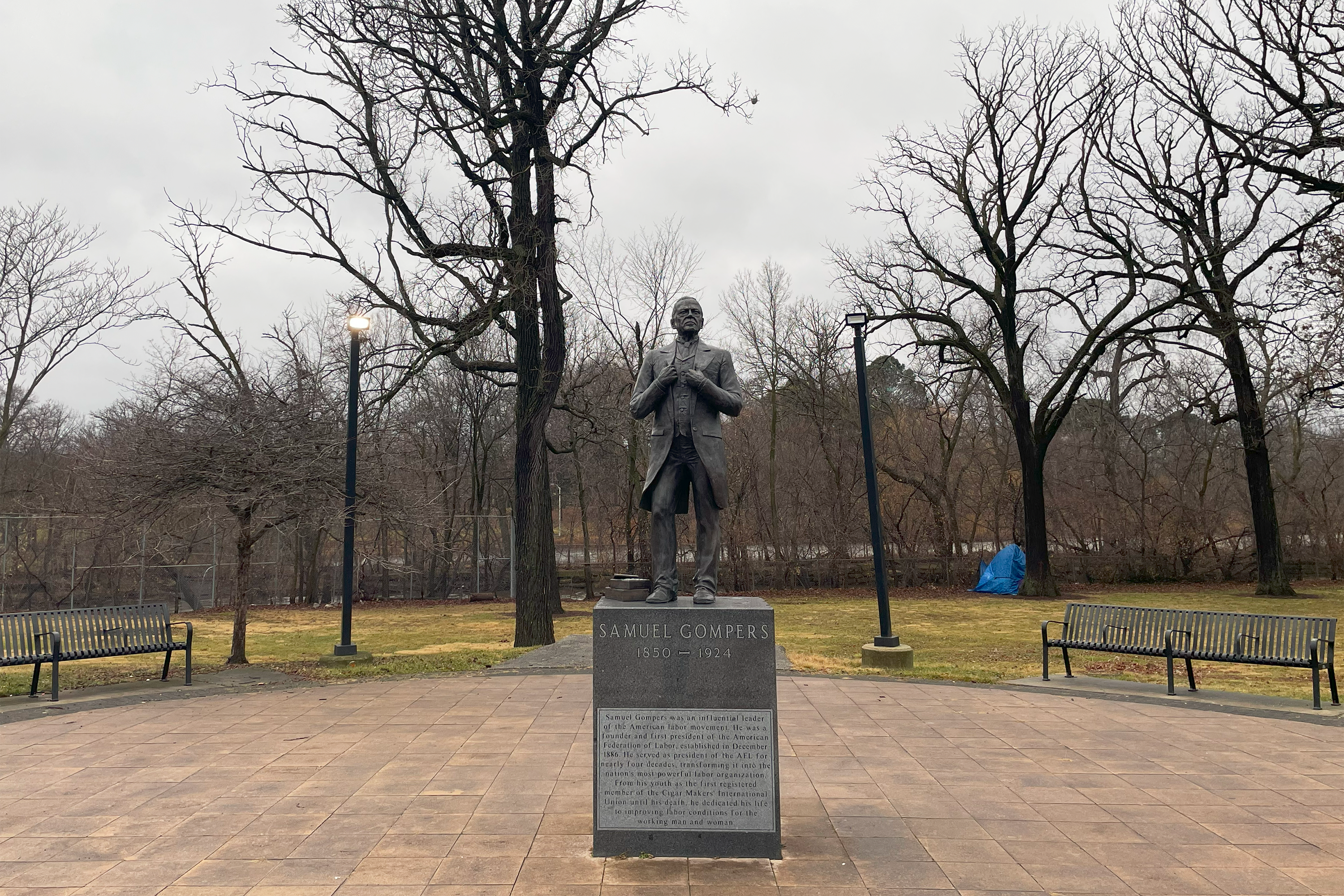

At the corner of Pulaski Road and Foster Avenue on Chicago’s Northwest Side stands a statue of labor leader Samuel Gompers, welcoming people to the park that carries his name. Cast in bronze, he strikes a dignified pose, hands assertively clasping his lapels, his eyes gazing off into the distance. At his feet are two boxes of cigars, a nod to Gompers’ roots as a cigar maker.

This is a relatively new statue in Chicago, unveiled in 2007. It recognizes, among other things, the founder of the American Federation of Labor’s fight for the eight-hour workday and the end of child labor.

For a man who helped achieve so much, Gompers looks small in statue form, compared to other monuments around the city. Or that’s at least what Curious City listener John Cahill thought. Cahill said he used to pass by the Gompers statue every day on way to work. And he often wondered whether its stature was meant to represent Gompers as an “everyman,” or if there was a different reason for its small size.

To answer Cahill’s question, we did a little digging.

We began by reaching out to the sculptor herself, Susan Clinard. Clinard said that when she was commissioned by Chicago’s 39th Ward to create a statue of Gompers, her instructions were to create a life-sized depiction. And Gompers was about five feet five inches tall — average height for a man of his time in the late 1800s.

So Cahill’s question to Curious City about the statue's height seems to be a matter of perspective. After all, so many statues are larger than life. And perhaps we’ve come to expect that.

But answering Cahill’s question about the statue’s height led us down a rabbit hole into Gompers’ life as a labor leader — and how the commission to build the statue changed the course of Clinard’s career not once, but two times.

A statue to celebrate the work of a labor leader

The Samuel Gompers statue was unveiled in the park that bears his name on Labor Day in 2007. It was greeted by a crowd of jubilant

Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1886 and served as its president for 40 years. It was in this role that he empowered local unions to achieve common goals including higher wages and better working conditions.

Back when she received the commission, earlier in 2007, Clinard was excited. She had recently left a career as a social worker in Chicago providing support for children in the foster care system. The working conditions and the low pay had worn her down, leading her to embark on a new career as a sculptor. A statue of the labor leader who helped bring about child labor laws seemed like the perfect way to blend Clinard’s passions.

Clinard remembers the day of the unveiling as one of the best such events she’d ever been to. “The celebratory pride of so many unions there on the unveiling day was palpable,” she said.

Gompers’ anti-immigrant past

Clinard held on to that feeling for six years. That’s when she posted a picture of the statue on Facebook for Labor Day. An acquaintance saw it and reached out to Clinard, telling her that Gompers was not the universally beloved labor leader many imagined him to be.

The acquaintance told her Gompers had been prejudiced against immigrant laborers — particularly people of Asian descent. “That was a punch in the gut,” Clinard said.

Labor historian Tim Messer-Kruse has written about the impact of Gompers’ efforts as a labor leader. He says Gompers primarily fought on behalf of white skilled laborers.

“He, more than any other single figure in the American labor movement, was responsible for constructing the Jim Crow structure of American unions right up until he died,” Messer-Kruse said. “I mean, he is ... primarily responsible for the fact that the AFL eventually becomes essentially an all-white movement.”

Gompers very publicly campaigned against Asian people immigrating to the U.S., even writing a book in which he argued that people of Japanese and Chinese descent were taking away jobs from white workers.

After learning about Gompers’ past, Clinard said she regretted not knowing more about Gompers before taking the commission. “I didn't know that about Gompers,” she said. “I should have known that about Gompers.”

The news changed the way Clinard thought about her work as a sculptor. She no longer had the desire to create statues to memorialize "incredible" figures.

Reckoning with the statue of Samuel Gompers

As a society, we’ve been asking ourselves what we should do with statues like the one of Samuel Gompers that both spark reverence and anger.

One approach is the Chicago Monuments Project, created in 2020 to take a comprehensive look at our public art. In the spring of 2022, the committee issued a report listing which pieces warranted attention or action. Samuel Gompers’ statue was not included on their list of problematic monuments.

But Messer-Kruse said he didn’t recommend taking the statue down. Instead, he thought updating the statue’s plaque or erecting an additional monument nearby could help provide additional context. “Maybe we need a statue to A. Philip Randolph, someone who opposed Gompers’ Jim Crow policies and was actively trying to change them,” he said. “[Randolph] was the first labor leader of color to become a member of the AFL-CIO executive board, after a lifetime of struggle.”

Do we need more statues or fewer? Different people recognized or different ways of recognizing them? These are questions artists, activists and city leaders are currently asking themselves and answering in different ways.

Meanwhile, on a corner on Chicago’s Northwest side, one can consider the ways Samuel Gompers improved our working lives as well as the ways he caused harm to those he excluded and ostracized. As the traffic whizzes by and families head to the park to play, passersby may wonder who the proud man in bronze is, not knowing the complicated answer.

More about our question-asker:

Skokie resident John Cahill used to live right by Gompers Park. Back then, John couldn’t help but take in the scenery — including the Samuel Gompers statue — while waiting for the light to turn at the busy intersection of Foster and Pulaski.

In a follow-up call we had with John, he was relieved to learn that the Gompers statue was true to the labor leader’s actual height, and not intended to belittle him in any way. However, after discussing Gompers’ xenophobia, John replied, “I feel like now we should maybe make the statue smaller, actually.”

John has lived in Rogers Park, Little Village, Lakeview, Portage Park, the South Loop and East Garfield Park. He says he cherishes this union town and its history.

Jeb Backe is a journalist and audio producer living in Chicago.