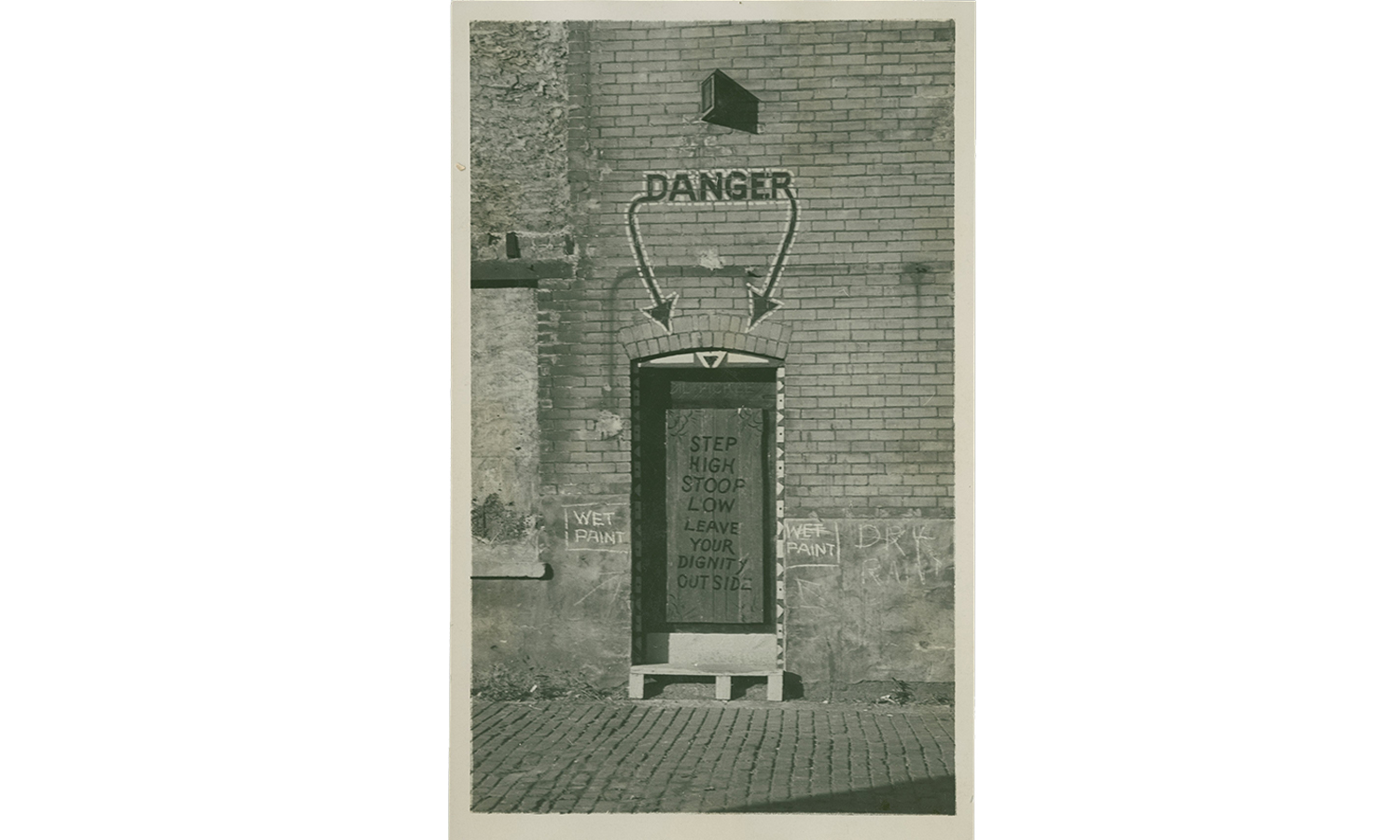

There’s a quiet, unassuming alley between Dearborn and State streets near the Newberry Library in the Near North Side neighborhood. With some overflowing dumpsters, rat poison signs, and a few scattered beer cans, it looks like a lot of other alleys in Chicago. But a hundred years ago, someone walking through this same spot would have come upon an orange door inscribed with the words, “Step High, Stoop Low, Leave Your Dignity Outside.”

From the mid-1910s to the early 1930s, that door was the entrance to one of Chicago’s most influential cultural spaces at the time: the Dill Pickle Club (sometimes Dil Pickle Club).

Paul Easton, a high school English teacher from Skokie who’s had a longtime fascination with Chicago literature and history, had heard about the Dill Pickle, but he wanted to know more. So he asked Curious City:

What was the Dill Pickle Club, and what happened to it?

The Dill Pickle was a political forum, theater, lecture hall, and nightclub. But above all, it was a hub for radical politics and art, where anarchists and labor agitators could spar or collaborate with playwrights, poets, painters, and journalists.

Like a lot of creative spaces today, as the Dill Pickle’s popularity grew, the club began to draw more mainstream visitors — and the neighborhood where it was located began to change as well. And while the Dill Pickle has been closed for nearly 100 years, the need for these kinds of accessible creative spaces in Chicago hasn’t changed.

The origins of the Dill Pickle

In the early 20th century, Chicago was experiencing rapid industrialization and growth.

“But it’s also a place that’s increasingly drawing artists, writers, people interested in the theater to it,” says Paul Durica, director of programs for Illinois Humanities and a Dill Pickle aficionado.

“And you know much like the city itself, they’re really interested in innovation.”

Chicago’s Tower Town (sometimes Towertown) neighborhood, located just west of what today is the Gold Coast, was a hotbed of that creative and political activity. Nowadays, the Gold Coast is known for its high-end shops and mansions, but in the early 1910s, Tower Town was the city’s “bohemian” district.

Radicals of all stripes mixed with writers, artists, hobos, and other transients. They often congregated in Washington Square Park, also known as Bughouse Square, to debate everything from Marxist theory to the benefits of an all-peanut diet.

“What you see happening in addition to all of these creative people moving into the area are the creation of almost what we call DIY spaces today,” Durica says. “The kind of scrappy little efforts that provided a place where people could come together, and create and commune.”

A well-connected labor organizer named Jack Jones recognized the need for a permanent space where these artists, activists, and intellectuals could all exchange ideas. Jones began by organizing meetings and events, and around 1917, he acquired a decrepit barn in Tooker Alley (sometimes known as Tooker Place), between Dearborn and State streets. That space would become the home of the Dill Pickle Club.

Like many stories about the club, the origins of its name are shrouded in myth and rumor. But supposedly, it came from an Irish political leader named James Larkin, who was living in Chicago in the 1910s and was close friends with Jack Jones.

“Apparently, [Larkin] was in a restaurant with Jack Jones and he was eating some pickles off a dish,” Durica says, “and he held one up and said there’s nothing finer in the world than this dill pickle. So that’s the name that they eventually gave this forum that they created.”

A space open to all

From the moment it opened, the Dill Pickle became known for being a place where anything goes and anyone was welcome, says Durica. One night, a professor might have given a talk about the morality of “free love,” followed by an impromptu one-act play, all accompanied by a barrage of audience heckling.

The air would have been thick with cigarette smoke, and you might have stumbled inside to find an Adam and Eve themed costume party or a lecture on “painless childbirth,” including a not-to-be-missed “moving picture of a Caesarian operation,” according to a flyer advertising the evening.

The club quickly grew into a kind of freewheeling, low-stakes creative workshop, frequented by writers like Carl Sandburg and Sherwood Anderson, journalist and screenwriter Ben Hecht, or actress Mae West.

“You might be able to order a cheap sandwich, you might be able to order a cup of lemonade, but what you’re really there for is the atmosphere, the conversation, for the spectacle of all of the different people that have gathered there that night,” Durica says.

Along with attracting artists and thinkers, the club was also was open to queer Chicagoans.

"It was one of the first places in the city of Chicago where people were having candid conversations about homosexuality,” Durica says.

“The Dill Pickle Club was famous for their masquerade balls, for their Halloween parties, and by all accounts, they had very visible expressions of intimacy among same-sex people at the Dill Pickle,” says Liesl Olson, the director of Chicago Studies for the Newberry Library, which houses an extensive collection of Dill Pickle records, handbills, and posters.

The club’s openness extended to other marginalized groups as well. One of the Dill Pickle’s most memorable figures was Dr. Ben Reitman. Reitman was known for providing medical care to prostitutes and low-wage workers, leading to his nickname “the hobo doctor.” Reitman also acted as the Dill Pickle’s promoter, drawing attention from his connections in academia and the press.

Durica says the club’s status as a cultural landmark is “largely because of the marketing and publicity that people like Reitman were doing in the ’20s, which established it for better or for worse as the heart of Chicago’s bohemian and artistic culture.”

The neighborhood changes

By the mid-1920s, in part thanks to frequent newspaper coverage, the Dill Pickle Club’s popularity outside of Tower Town started to grow. But that attention wasn’t always a good thing.

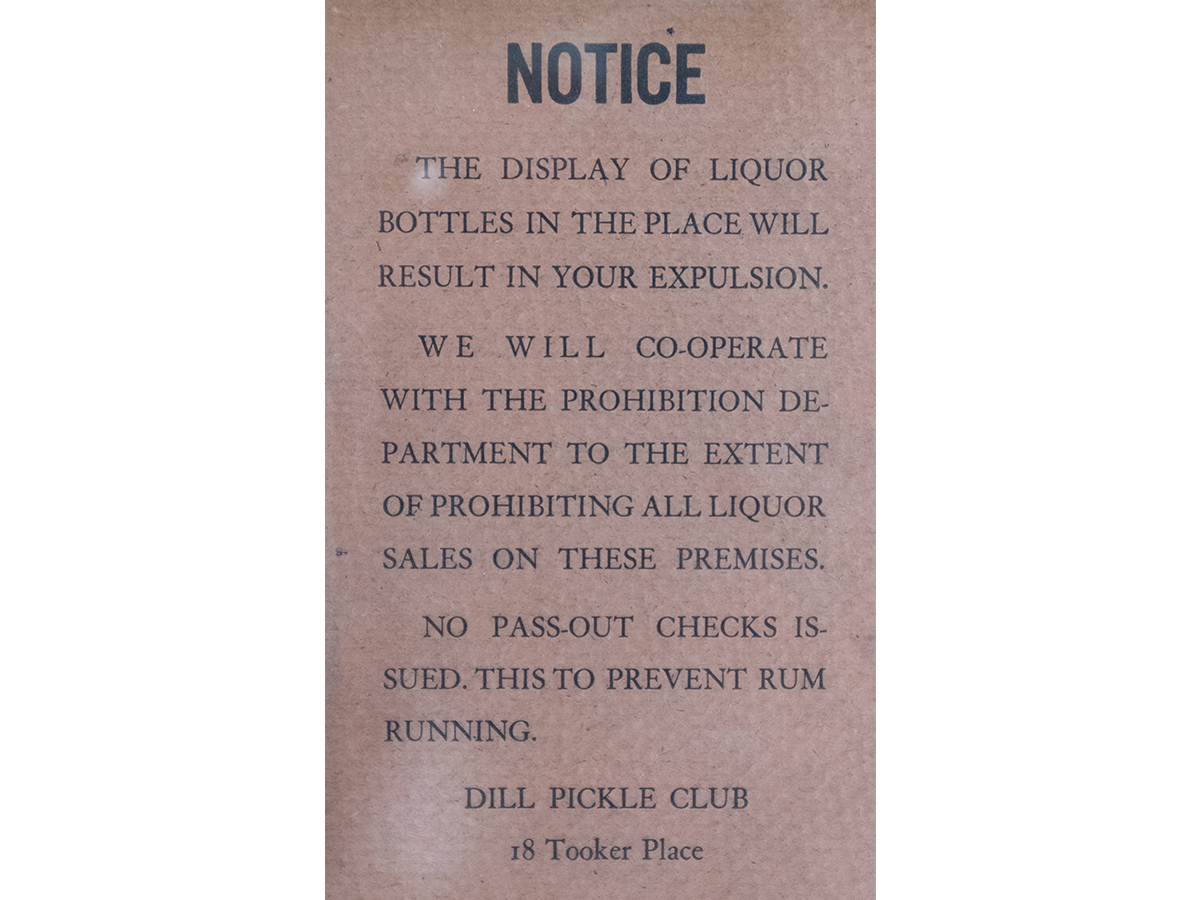

Initially, the club didn’t serve alcohol, although that never stopped anyone from bringing in a flask to top off their lemonade or coffee. But after Prohibition was enacted in 1920, organized crime and corrupt local officials allegedly pressured Jones into selling illegal booze. The mob’s presence led to complaints from neighbors about the noise and increased police attention. Jones was arrested several times, and this put the club in the headlines.

At the same time, the club’s growing notoriety was beginning to attract more middle-class professionals who were looking to observe and be entertained by the bohemians.

Olson says that by 1930, the Dill Pickle “was well-known in the city. It even turns up in some guidebooks in the city. If you want to experience the real Chicago, maybe you go visit the stockyards, maybe you go to the Dill Pickle Club, in that there was something quintessentially Chicagoan about the [club].”

As the club became more popular, the Tower Town neighborhood also began to change.

“It’s remarkable how similar it is to [what] someone who lived in Wicker Park in the ‘90s would say about it now, or maybe even Logan Square 10 or 15 years ago, would say about that neighborhood,” says author Daniel Kay Hertz, who writes about the gentrification of Tower Town in his book The Battle of Lincoln Park.

“There’s totally this sense that feels very modern, like, these people with more money but [who] are less interesting have come in and sort of ruined our neighborhood and taken it over, “ Hertz says.

The neighborhood’s rising prices, buoyed by the newly built Michigan Avenue bridge which connected Tower Town to the Loop, caused many bohemians and artists to move out.

“I don’t want the takeaway to be, ‘Oh, the Dill Pickle Club gentrified Tower Town,’ but the Dill Pickle played its role, which was partly to attract people who otherwise would not have come to the neighborhood to the neighborhood,” Hertz says.

Essentially, the radical underground wasn’t so underground anymore.

But the final death blow to the Dill Pickle was really the Great Depression. The club stopped bringing in money and was forced to close its doors roughly around 1931, Durica says. Over the next few years, Jack Jones tried to reopen several times in other locations but was never able to recapture the success he had in Tooker Alley.

The Dill Pickle and creative spaces today

While the Dill Pickle has been gone for almost a century, the spirit of the club, with its focus on artistic innovation and freedom, lives on in Chicago.

“It’s not so much that the Dill Pickle Club had a direct legacy where you can say, ‘Ah, the Dill Pickle, then the owners went on and opened this other place,’” says Bill Savage, an English professor at Northwestern, who focuses on Chicago literature and culture. “But structurally speaking, in the urban creative environment, the need for that kind of place never went away.”

Savage says the club’s model of accessibility, where anyone could lecture or perform or stage a play or strike up a conversation with a stranger, has acted a model for artistic and intellectual gathering places in Chicago that lasts until today.

He offers a few examples, like the Green Mill jazz club and music and performing arts venue The Hideout. There are also spots like The Co-Prosperity Sphere in Bridgeport, Comfort Station in Logan Square, the South Side Community Art Center, and countless other storefront theaters and DIY spaces across the city.

“We have an amazing creative scene happening in this town that has artistic angles, and political angles, and literary angles, and it all happens in semi-public places where people who own it happen to be interested in fostering creative communities of many different sorts,” Savage says. “It’s easy and fun to look back at the history of the Dill Pickle, but ya’ oughta look up and say: ‘Where’s it going on now?’”

More about our questioner

As a kid growing up in the south suburbs, Paul Easton and his family would visit communist bookstores and attend cultural events like Ban The Bomb concerts. Easton says this forged in him a certain protest spirit, which he sees reflected in the Dill Pickle Club.

“[It sounds] like a place where all Chicagoans could kind of go, and be themselves, and do what they do, and I just love that sort of crazy insanity,” Easton says. “It sounded like a place that I would have loved to have gone to.”

Easton is currently teaching George Orwell’s 1984 to his high school students, which he says showcases the importance of learning about history and the past. He says that same lesson can be applied to places like the Dill Pickle.

“For me, knowing something about Chicago’s history helps keep me tied to my humanity,” he says. “And the Dill Pickle Club was probably a place where people could be human, more than anything else, so I like that.”