If you stand at the corner of Lawrence Avenue and Broadway in the Uptown neighborhood, you’ll see two famous Chicago music venues: the Riviera Theatre and the Green Mill. The Uptown Theater, which closed to the public in 1981, looms behind them. And looking east down Lawrence, beyond the “L” tracks, you can see the tall vertical sign for the Aragon Ballroom, yet another legendary spot for experiencing live music.

Karen Kinderman lives nearby this cluster of music venues, and she’s wondered why they were all built in this small section of her neighborhood. So she came to Curious City to find out how Uptown became the entertainment center it looks like today.

Today’s concert goers might think of Uptown as a place to see live rock and pop music at the Riv and the Aragon, or jazz at the Green Mill. But the development of these venues was influenced by other sorts of entertainment that were popular a century ago: cabarets, motion pictures and dancing. And their locations were determined by the way the Uptown neighborhood itself developed, shaped by the region's geography and its transportation networks. It's a history stretching all the way back to the 1800s.

Cemetery saloons form on Clark Street

Back in 1860, Uptown was a rural area miles north of Chicago’s city limits — located within Lake View Township, which had a population of only 586 people spread out across 10 1/2 square miles. At the time, people flocked to the area to visit the cemeteries there.

Many city residents were clamoring for new cemeteries to open in the countryside to make room for the dead outside the crowded city. Graceland Cemetery opened in 1860, at the south end of what’s now defined as Uptown. Further north, German Catholics founded St. Boniface Cemetery in 1863.

Clark Street, which today runs along the west edge of both cemeteries, used to be a muddy track for stagecoaches traveling between Chicago and Wisconsin. Roadhouse taverns opened along the route to serve these travelers. Many of these saloons were near the cemeteries, drawing crowds of people who’d come to attend a funeral or visit a family member’s grave.

“It is by no means unusual to see a whole funeral procession drawn up at one of these resorts,” the Tribune reported in 1890. “The experienced driver on the (hearse) takes no chances. He has an understanding with certain places. … He is given at least all the whiskey he wants in return for ‘steering’ the mourners to these places.”

One of those popular cemetery waysides, Sunnyside Park, began advertising outdoor concerts in 1895, with performers including the Royal Hawaiian National Band, German and Swedish choirs, opera troupes, military bands and orchestras. Forty thousand people filled Sunnyside Park on Sept. 3, 1899, to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the German author Goethe’s birth, watching a performance by some 2,000 singers and musicians. But after the venue closed in 1903, houses and other buildings were constructed on the land.

Another cemetery saloon was right across from the entrance to St. Boniface Cemetery. In 1918, it became Rainbo Gardens, a popular spot for live music, dancing and drinking.

A third cemetery saloon that opened as early as 1897 was just east of St. Boniface: Charles E. “Pop” Morse’s roadhouse, which would later be replaced by the Green Mill. In its early years, “Pop” Morse’s place was both a tavern and a training facility for boxers. Visiting Chicago for prizefights, boxers from Brooklyn, Philadelphia, and Buffalo trained with the punching bags in the back room. In that era, most of the land around the Green Mill’s future site was vacant, resembling a park. During wintertime, people gathered at Pop’s saloon and other local roadhouses to watch horse races on the neighborhood’s snowy streets.

The “L” arrives

At the turn of the 20th century, Uptown’s center began to shift from Clark Street to the area east of the cemeteries — because that’s where train lines were being built.

The Northwestern Elevated Railroad started running speedy electric trains from the Loop to Wilson Avenue in 1900, using the same “L” tracks known today as the CTA’s Purple Line and Red Line. The decision of where to build those tracks was fateful. It influenced where homes and businesses were built — and it eventually sparked the rise of Uptown’s entertainment scene.

As the CTA’s Graham Garfield explained in a 2016 Curious City story, private companies built the original “L” lines, and they followed the path of least financial resistance when they bought up properties to create their routes.

Real estate developers also pushed for train lines to run through Uptown, which the city of Chicago had annexed in 1889, as they knew better transportation would boost property values.

Charles Tyson Yerkes, the controversial tycoon who controlled the Northwestern Elevated, addressed a crowd of VIPs on the Wilson Avenue “L” platform on May 31, 1900, the railroad’s first day of operation.

“It is a good structure; there is none better, and it runs through the best section of Chicago,” he said. “We do not doubt that many people living on the South and West Sides will now give up their homes and come over here to ride on the Northwestern Elevated.”

As Yerkes and others predicted, the population boomed. In 1900, the area east of Clark Street from Montrose Avenue north to Foster Avenue — which covers the bulk of Uptown — had about 2,300 residents. Thirty years later, Uptown’s population would jump to 67,699. And as increased transportation brought more residents and visitors to the neighborhood, entertainment venues began to open near “L” stations, like the Wilson Avenue Theater and the Arcadia Ballroom (at the site where the Wilson Yard complex, including Target, stands today).

And in 1914, Green Mill Gardens opened its doors, replacing Morse’s Cafe. It included the structure that still stands at the northwest corner of Lawrence and Broadway, but back then, it stretched for an entire block along Lawrence Avenue, with a terraced beer garden behind the building. “The coolest spot in Chicago,” an advertisement proclaimed.

Around this same time, the city renamed Evanston Avenue, calling it Broadway. Business owners on the street had suggested the new name, which evoked the glitz of New York City’s theaters.

Uptown’s entertainment venues began attracting residents from the neighborhood, as well as other people from around the city.

“I’d argue the Uptown nightlife comes from it being a densely populated, renter-oriented district — i.e., lots of people with day jobs downtown, wanting to get out at night and have some fun,” says Bill Savage, an English professor at Northwestern University.

Uptown becomes a hot spot for shopping

As “L” trains and streetcars made it easier for people to get around the city, more Chicagoans shopped in outlying neighborhoods. Uptown residents could buy goods in their own neighborhood, and the area also attracted shoppers from other parts of the city.

“There’s money here, with at least a quarter of a million people all in a bunch,” remarked Loren Miller, who opened the Loren Miller & Company Department Store in 1915 on Broadway south of Lawrence (in the same building that later became Goldblatt’s).

Miller promoted the area around his store as a new shopping zone that could rival the Loop, and he claimed credit for coming up with a new name for the neighborhood.

“It’s plumb foolishness to say that our wives and daughters yearn to travel five or six miles into town to buy dry goods, or even millinery, or coats and dresses,” he later recalled telling a fellow businessman. “… Women prefer going just around the corner for most of the things they need.”

It should be called Uptown, he said — “the aristocratic antithesis of downtown.” The area immediately around Miller’s store became known as Uptown Square, and its rise as a bustling shopping district made it an attractive place to open theaters, dance halls and nightclubs.

Miller started the Central Uptown Chicago Association, a business group that ran advertisements promoting Uptown as the “Shopping Center of a Million People.” One of the ads suggested: “Make tomorrow an Uptown Chicago Day — shop in the morning, swim in the afternoon, and dance or see a show in the evening.”

Dave Jemilo, who has owned the Green Mill since 1986, says Uptown’s emergence as a shopping area in the 1910s and 1920s created a demand for entertainment.

“If there’s so many stores and 10,000 people … shopping on a weekend, it just makes sense to put some entertainment where all these people are going to be,” he said.

Enter cabarets, movies and the dance craze

Uptown’s growing entertainment scene was also shaped by the ways Americans enjoyed spending their leisure time in the 1910s and 1920s, including three important trends: cabaret, movies and dancing.

The Green Mill and Rainbo Gardens were cabarets, a style of entertainment venue that emerged in America around World War I, influenced by similar places in France and Germany.

“Chicago was really the leader in the beginning of that kind of entertainment in the United States,” said Charles A. Sengstock Jr., author of That Toddlin’ Town: Chicago’s White Dance Bands and Orchestras, 1900–1950. “It set up a feeling of intimacy between the entertainer and the audience that could not be realized in a theater.”

During that same era, moviegoing was a national craze, just two decades after the very first motion picture parlors had opened. In 1918, the 2,600-seat Riviera Theatre opened a block south of Green Mill Gardens, with a 30-piece “synchronizing symphony” performing during the silent films.

The Riviera was the second theater built by the legendary Chicago company Balaban & Katz. According to movie historian Douglas Gomery, Balaban & Katz decided to build its earliest theaters in neighborhoods with growing populations, such as Uptown — “near fans who had just moved to what were then outlying districts. New mass transit made access simple.”

In the following years, Balaban & Katz bought up Green Mill Gardens’ outdoor space. That L-shaped property was where they opened the Uptown Theatre in 1925.

“They spared no expense in creating the most modern and lavish theater probably that the country ever knew — and will ever know,” historian John Holden said.

A Balaban & Katz advertisement called the Uptown Theatre “a spacious playhouse of magnificence to meet the requirements of this progressive and rapidly growing community.” When the theater opened, its marquee boasted: “An acre of seats in a magic city.” With 4,381 seats, it was the world’s largest theater, a distinction it held until New York City’s 6,500-seat Radio City Music Hall opened seven years later.

And this amount of seating was necessary to satisfy Chicago’s moviegoing craze. Per capita movie attendance would hit an all-time high in 1930, when Americans bought an average of 38 movie tickets during the year, according to historical research. That compares with an average of 3.8 tickets in 2019.

But films weren’t the only entertainment the Riviera and Uptown theaters offered its audiences; they also featured musicians, dancers and comedians in between the movies. Uptown Theatre ads promised “a stage show of enough splendor to match the startling grandeur of the theatre itself.”

Dancing was also phenomenally popular during this time, referred to as the Jazz Age — a trend that led to the opening of the Aragon Ballroom in 1926.

“Dancing was the prime social activity of the time,” Andy Karzas, whose family owned the Aragon, said in a 1963 WFMT interview with Studs Terkel. Karzas recalled that the dancers at the Aragon were “mostly young people, even late teens and in their early 20s, single people, unmarried. This was the wonderful place for courtship in Chicago. What nicer place for a fellow to take a girl for an inexpensive evening of entertainment?”

At the Aragon, people danced the two-step, waltzes and foxtrots to mellow music played by orchestras and bands of 13 or 14 musicians, led by stars such as Wayne King, “The Waltz King.”

“Conservative-style ballroom dancing is what it was,” said Sengstock, who danced at the Aragon in the 1940s and 1950s.

Uptown’s ups and downs

Of course, Uptown wasn’t the only Chicago neighborhood with theaters and concert venues. For example, the South Side’s Bronzeville was the hot spot for jazz. But by the late 1920s, Uptown was hard to beat.

“It really must have been something,” historian John Holden said. “I can’t imagine what that intersection of Broadway and Lawrence would have been like at the height of its popularity. Undoubtedly, there were thousands and thousands of people going every which way.”

In the following decades, however, Uptown’s glamour faded.

“There was a major push right out of World War II for people to get out of the cities, which were considered crowded and dirty and obsolete, and go out to new suburbs that were accessible from the new expressways,” Holden said. “So there was a mass exodus of the middle class ... from areas like Uptown. And they were supplanted by very poor people, for the most part.”

At the same time, tastes in entertainment were changing. Movie attendance began dropping around 1950, and continued falling as people often chose to stay home and watch television. Big movie palaces like the Riviera and the Uptown went out of style.

Ballroom dancing also waned in popularity, hurting attendance at the Aragon. “Young people today, the fellows don’t want to learn how to dance,” Andy Karzas lamented in 1963. “ … They do a lot of gyrations in record stores, but they don’t learn beautiful ballroom dancing.”

The Aragon shut down as a dancing ballroom in 1964, but four years later, it was reborn as a hall for rock music, featuring concerts in 1968 by the Shadows of Knight, Herman’s Hermits and Jefferson Airplane. Now owned by Live Nation, it was officially renamed the Byline Bank Aragon Ballroom in 2019.

Rainbo Gardens became Uptown’s major venue for rock music in the late 1960s. Known as the Electric Theater and later as the Kinetic Playground, it hosted concerts by Led Zeppelin, the Who and Muddy Waters, among many other big names. Later, it became the Rainbo roller rink, which was demolished in 2003; a residential building stands at the site today.

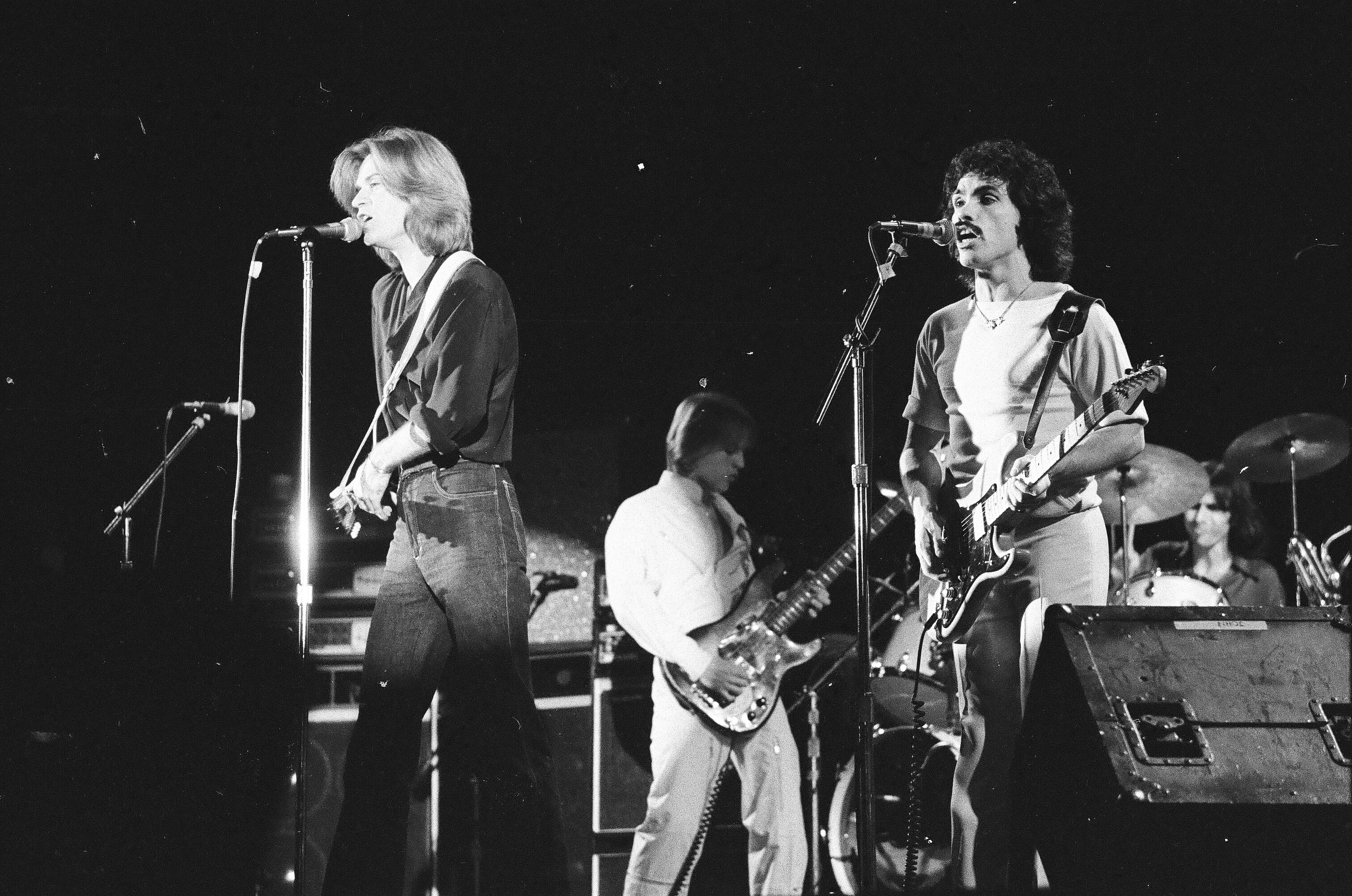

After featuring a mix of movies and concerts in the late 1970s, the Riviera became a rock venue in 1986. It’s now owned by Jam Productions.

The Uptown Theatre screened movies as late as 1978, but it had started presenting rock concerts around 1974 — including 17 shows by the Grateful Dead, eight by Frank Zappa and three by Bruce Springsteen, according to setlist.fm. But the massive auditorium has been closed since Dec. 19, 1981, when the J. Geils Band performed.

In 2018, the city announced a $75 million plan to restore and reopen the Uptown Theatre. Last November, the building’s owner, Jerry Mickelson of Jam Productions, told the Tribune that he was working to secure the final $26 million to complete the project’s financing. If it reopens — and retains something close to its original seating capacity of 4,381 — the Uptown would again reign as the city’s largest theater.

Meanwhile, developers unveiled plans in February to open a theater in the building where the Wilson Avenue Theatre operated more than a century ago, before the structure was converted into a bank. The Double Door rock venue, which closed in Wicker Park in 2017, is reportedly a possible tenant for the space.

Throughout the area’s continuing evolution, there wasn’t any master plan to create an entertainment district in Uptown in the early 20th century. But considering how the neighborhood developed, it’s no surprise that one sprang up anyway.

“Those places — the Aragon and the theaters — were not just placed there by accident,” Sengstock said. “They were placed there because that’s where the people were going.”

But even throughout all of Uptown’s ups and downs over the past century, the Green Mill has been there. An upstairs cabaret space closed decades ago, leaving the Green Mill as a small cocktail lounge. Since Dave Jemilo bought the nightclub in 1986, it has been one of Chicago’s best places to see live jazz.

“When I bought the joint, I found some envelopes in the office,” Jemilo said. Those envelopes included advertisements from the 1920s, touting Uptown as a glamorous destination for shopping and entertainment. “It said, ‘All roads lead to Uptown.’”

More about our question asker

Karen Kinderman, who works as a speech language pathologist at Northwestern University, moved to Chicago from the Bay Area 12 years ago, and she’s lived in Uptown for the past decade. She says her curiosity about the history of the neighborhood’s music venues was sparked by a historical walking tour.

“It was just interesting for me to think about having so many theaters all in one place — thinking about the vibrancy of having such a place for artists and people to gather,” she said.

Karen hasn’t seen a show at the Riviera, but she’s enjoyed attending concerts at the Aragon and the Paper Machete “live magazine” variety show at the Green Mill.

“Both the Aragon and the Green Mill felt very much like stepping into a bygone era,” she said. “With the Aragon … just standing in the ballroom itself and listening to live music was electric. With the Green Mill, it’s fairly dark inside … Thinking about them being part of that Jazz Age was exciting.”

Robert Loerzel is a freelance journalist. Follow him at @robertloerzel.