Curious City has gotten a lot of questions about famous pranks, so in celebration of April Fools’ Day we investigated three historical stunts pulled by (or on) local media.

To help with the backstory, we turned to historian Paul Durica, who’s the director of exhibitions at the Newberry Library and someone with a long-standing interest in the weird backwaters of Chicago history.

Durica told us three tales of Chicago media hijinks: The first involves a killer hawk allegedly terrorizing local pigeons. The second includes a man who hijacked television airwaves — but didn’t have a plan regarding what to do next. And the third is about a phony bar started for the sole purpose of entrapping corrupt officials.

Captain Kidd, The Killer Hawk

The winter of 1927 was a bad time to be a pigeon in the Chicago Loop. Along with the usual threats of cold temperatures and a scarcity of food came the possibility of a sudden death from above in the form of a hawk known as “Captain Kidd.”

The hawk first appeared in a newspaper article in the Chicago Journal early in January 1927, when a reporter wrote that he had seen a “rather large hawk” dining on pigeons on the steps of the Art Institute of Chicago.

But was the story based in reality?

“For some reason, this story completely captured the attention of Chicago, and made headlines day after day,” Durica said.

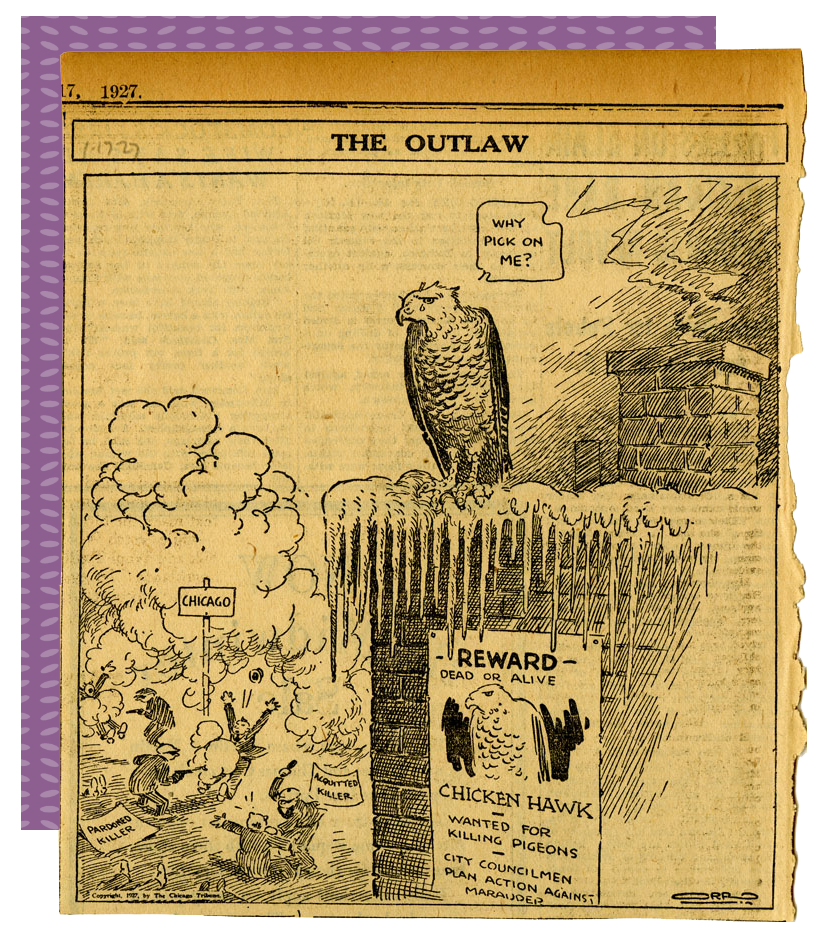

Hawk hysteria had reached such a fever pitch by mid-January that the Journal and the Chicago Tribune offered a reward for the kill or capture of Captain Kidd. The Tribune set the highest bounty: $50 dead, $100 alive.

The newspapers kept tabs on the hunt. Here’s how the Tribune summed it up:

“To date the record reads: one peaceful hawk shot and killed in a tree in Garfield Park; one half frozen hawk rescued, rather than captured, at the Chicago Beach hotel, and one hawk said to have been lured into a mesh spread on the roof of the Transportation Building. Then there was an owl, at first mistaken for a hawk, which killed itself by flying against the walls of the County building. And it still looks as if Captain Kidd, happy in his reflection that there’s safety in numbers, will make his way over the loop today and tomorrow and for the days thereafter in peace and plenty.”

The court of public opinion was divided about Captain Kidd: Some despised the hawk for killing harmless pigeons, while others thought it was doing a public service. Two aldermen actually proposed hawk-related resolutions to the City Council. Even the Board of Trade had an opinion (they were pro-hawk, anti-pigeon).

But then, just as swiftly as Captain Kidd had swooped in, the bird disappeared from the news coverage, Durica said. The Chicago Journal announced it would be publishing a serialized fiction column, “The Hawk and the Pigeon,” and the sightings and subsequent hysteria were dismissed as a sort of 1920s viral campaign, all engineered by the Journal — which the Journal of course denied.

Then, in April of that year, the Tribune reported that Captain Kidd had finally been captured by Larry McGil, who had used his umbrella to render the bird unconscious on an El platform.

“Whether the newspapers had hoaxed one another or the public remains an open question. All we have is the sensational reporting at the time. So, was there one killer hawk, multiple hawks, or none at all? We still don’t know,” Durica said.

The Max Headroom Signal Hijacking

It was the Sunday before Thanksgiving in 1987, just past 11 o’clock at night, and Doctor Who was on WTTW. Suddenly, the picture cut out and a man in a Max Headroom rubber mask appeared on screen. For almost two full minutes, this entity controlled the WTTW airwaves.

The viewers of Doctor Who didn’t know it, but this was actually the second appearance that evening of the Max Headroom impersonator. Two hours earlier, he’d managed to hijack a WGN news broadcast just as they were sharing highlights from a Bears game.

Hijacking a television transmission is no easy feat. It takes a lot of technical knowledge combined with highly specialized equipment and an immense power source.

So considering the effort that must have gone into this prank, you'd think that Max would have planned something to say or do. Instead, the surviving footage suggests that once the signal was hijacked, Max largely improvised — including pulling down his pants to expose his posterior so a woman could spank him with a flyswatter.

Viewers were perplexed, and angry complaints flooded WTTW, Durica said. The FCC opened an investigation — pirating television signals was a pretty serious offense — but they were confident the man behind the mask could be identified and brought to justice. That never happened. Evidence suggests it was someone with inside knowledge of the two stations’ operations and some kind of personal grievance against WGN (and, specifically, sports announcer Chuck Swirsky), but no arrests were ever made.

To this day, the “Max Headroom incident,” as it’s commonly called, remains one of the greatest pranks in broadcast history, Durica said.

The Mirage Tavern

In 1977, journalist Pam Zekman and her colleagues kept receiving complaints from small business owners that city inspectors were demanding bribes either to facilitate permits or to ignore code violations.

“They complained about it, but they didn’t want to cooperate on an investigation for fear that if they went public with their complaints, the city powers that be would shut them down. Understandable fear,” Zekman told WBEZ in a 2012 interview.

So Zekman pitched an idea to her editor at the Chicago Sun-Times. If they wanted to break this story, they needed to catch the corrupt inspectors in the act. Zekman’s proposal was simple: “The only way to document this kind of thing was to become the victims... start our own business, and see what happened.”

Zekman and investigator Bill Recktenwald of the Better Government Association assumed the identities of Pam and Ray Patterson, a married couple looking to buy a bar. And with a $5,000 down payment, they took ownership of a ramshackle dive on Wells Street. They did some renovations and opened for business under a new name: The Mirage Tavern.

Right away, everyday corruption appeared. Their broker taught them how to cook their books and pay off city officials with envelopes of cash. Various city inspectors expressed their desire for personal payments to overlook problems, like leaky pipes and maggots, or fast-track permits. And it wasn’t just city officials. Suppliers of standard bar amenities like pinball machines and jukeboxes had their own crooked demands.

The corruption was widespread, but it was also pretty low-rent: Most people expected very small payoffs of $10 to $25.

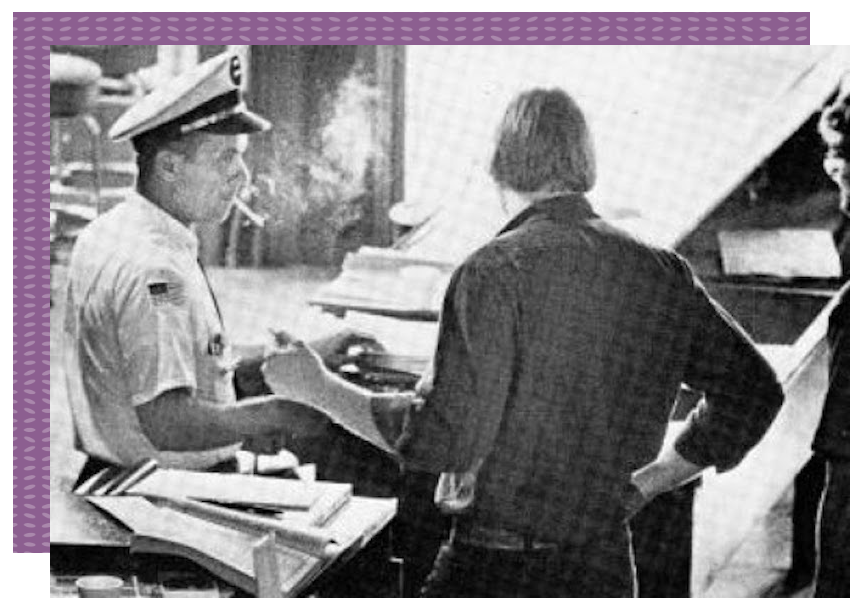

Unbeknownst to all these inspectors, the Mirage had an uncommon architectural feature: A hidden compartment above the restrooms that allowed Sun-Times photographers to look out on the bar’s main floor and snap pictures of everything.

“The photographers did an incredible job, you know we had some idea when the inspectors were gonna come, but not always,” Zekman told WBEZ in 2012.

In addition to documenting corruption, the reporters also had to actually run the tavern. One of them went to bartending school so he could keep up with customer demands. But not Zekman. She said one morning she was working the bar alone when some people came in and ordered margaritas.

“I didn’t know how to make the salt stick to the edge of the glass, didn’t know what went into a margarita. And the customers had to guide me. Which must have been weird to them,” Zekman said during the 2012 WBEZ interview.

After four months, the Mirage Tavern closed, and the Chicago Sun-Times released a 25-part series telling the whole story. The reporting produced results: Some city inspectors had charges brought against them, and the mayor formed the Office of Professional Review to combat corruption.

The Mirage reporting was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, but was ultimately rejected. Ben Bradlee — the executive editor of the Washington Post, known for his role in the Watergate reporting — served on the Pulitzer Prize Board at the time. He put it this way: “We instruct our reporters not to misrepresent themselves, period. We felt a Sun-Times award for this entry could send journalism on a wrong course.”

But not all were critical of the use of a hoax to expose a larger truth. The Columbia Journalism Review, appropriately enough, awarded the reporting an “imaginary prize."

This story was inspired by a question from a Curious City listener.

Steven Jackson is a senior producer for Curious City. Get in touch with him at sjackson@wbez.org.

Paul Durica is the director of exhibitions at the Newberry Library.