The Great Chicago Fire, which lasted from October 8-10, 1871, destroyed most of Chicago from what is today Roosevelt Road to Fullerton Avenue and from Lake Michigan to the Chicago River. Almost 100,000 Chicagoans lost their homes and several hundred lost their lives during the three days the fire burned.

But in 1871, the ever-growing city also had a west and a south side that were left mostly undamaged — areas of the city whose residents, largely working class, opened their homes to those who’d become refugees as a result of the fire, and whose industries played a big part in helping Chicago rebuild.

Even if we consider only the areas of Chicago impacted directly by the fire, there were a number of other buildings that remained standing once the fire was over. There was the Water Tower on Michigan Avenue, which over the past century-and-a-half has become a symbol of the city’s resilience, referenced as recently as such in an episode of Netflix’s “Chicago Party Aunt.”

The water works may have failed to function in the middle of the fire, but when the last of the embers cooled, that stone tower stood tall amid the ruin, proving a point around which all the city could rally and rebuild.

But the Water Tower was not the sole survivor of the fire. The Mahlon D. Ogden House, the Lind Block and the Relic House each tell a piece of Chicago’s history. And while these structures “survived” the fire, they were all torn down in the decades that followed as the city grew, neighborhoods gentrified and developers came knocking.

The Mahlon D. Ogden House

Mahlon D. Ogden was a prominent lawyer and the brother of William Butler Ogden, who served as Chicago’s first mayor. Ogden High School in West Town and Ogden Avenue, which runs from the Near West Side all the way to Aurora, are named after William Butler Ogden.

William Butler Ogden made a fortune in real estate and railroads — investments he brought his brother into, when Mahlon moved to Chicago.

By 1871 Mahlon Ogden was living with his second wife and three children in a two-story mansion just north of the fashionable Washington Square Park, which still exists today, at Clark and Walton Streets on the Near North Side.

When the fire struck on October 8th, 1871, Ogden and his family weren’t home. Their house was saved thanks to the efforts of some guests staying there and, presumably, the family’s servants.

The open space of Washington Square Park slowed the fire’s advance while those inside took everything made of cloth — curtains, carpets, blankets and sheets — and soaked them in well water and cider in the cellar. Then they wrapped the outside of the house like a mummy and waited out the flames.

When the fire had passed and eventually was extinguished by the rain that fell on October 9th, Washington Square Park lay in ruins. Its majestic elm trees had been reduced to ash and its elegant iron fencing had melted into large, tangled lumps.

But the Ogden house stood unscathed. As the Chicago Tribune reported, “The house of Mr. Mahlon D. Ogden, on Dearborn street and Lafayette place, was not even scorched.”

In the days following, tents began to appear in Washington Square Park as refugees from the fire took up temporary residence there. Outside help arrived but so did those who saw opportunity amid the ruins. Individuals photographed the Ogden house and turned the images into stereoscope cards that were sold all across the country.

More than two decades later, readers of the Chicago Tribune opened up the October 9, 1893 edition and were gifted with a full-color illustration of the Ogden house. The accompanying text proclaimed, “as the sole survivor on the north side it will always be famous.”

This was the year of the World’s Columbian Exposition and October 9th was Chicago Day at the World’s Fair. The special ticket for that day included an illustration of the mythical Phoenix rising from the flames — for that was how Chicago saw itself 22 years after the fire, a city reborn.

But Chicagoans wouldn’t have been able to see the Mahlon D. Ogden house on that day.

Soon after the fire, Ogden suffered financial troubles and the trustees of the Walter Loomis Newberry estate saw an opportunity to snatch up some valuable land. They tore down the mansion and erected, as a Tribune article from October 9, 1893 put it, the “magnificent new Newberry Library Building.”

There were no protests when the house came down. The public’s ideas about what was important and worth saving were different back then, and as the article went on to say, “in Chicago all things change.”

The Relic House

Going back to the time of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, while the Ogden House may no longer have been standing, that didn’t mean Chicago wasn’t looking for some survivor of the Great Fire to feature in the World’s Fair.

In a December 28, 1890 article a Tribune writer suggested he had the perfect structure to fulfill this role, and its owner, a man named WIlliam Lindemann even went on record saying, “Yes, I will move it to the World’s Fair grounds if I am paid enough. It would make a good American curiosity.”

The “it” Lindemann was referring to was the Relic House, and it was indeed an “American curiosity.”

The Relic House wasn’t a survivor of the Great Chicago Fire like one might imagine. It didn’t come into being until 1872. And yet it was a survivor in a certain sense.

Every brick and stone, every piece of glass and twisted metal that formed the walls of the Relic House had been salvaged from the ruins of the fire. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of a building, a single structure made up of the bits and pieces of a score or more of others.

The same Tribune article from December 28, 1890 described it this way: “The most interesting and ornamental monument of the fire is the ‘Relic House,’ well-known to North-Siders and Lincoln Park visitors. In 1872 when the ‘leavings’ of the fire could be had for the asking or the trouble of picking them up, a man named Rettig conceived the idea of building a small cottage out of such material as a melted mixture of stone, iron, and other metals.”

For ten years, the “House” seems to have been a private home. Then it was sold and moved to where it became a saloon. Then Lindemann bought it and added an outdoor beer garden. Various everyday objects that survived the fire hung from the saloon’s walls. A large painting depicting the fire reminded visitors of the scale of the disaster.

While the phrase wouldn’t have been used at the time, the Relic House was a “tourist trap.”

In 1920 the Relic House was taken over by Dr. Ben L. Reitman. Reitman had been the speaking tour manager and lover of the anarchist Emma Goldman, promoted birth control and sexually transmitted disease and infection awareness and attended to the medical needs of the homeless. He also performed abortions before they were legal.

After he was kicked out of the infamous bohemian forum and hangout the Dil Pickle Club, Reitman decided to form his own. Where did he go? To that old “American curiosity” leftover from the fire, the Relic House.

There he founded what he called the “House of Blazes.” “Poetry in the Relic House!” proclaimed the Tribune in 1920. “Verse flowing where good beer foamed since Lincoln Park was a grassy plot!”

Reitman tried to get those that gathered at the Relic House to discuss how they’d feel “if your wife runs off with your neighbor.” Few took him up on the offer. Not surprisingly, the “House of Blazes” lasted only a few months before Reitman returned to the Dil Pickle Club. And the Relic House lasted only a few more years.

In February 1929, it was torn down, along with many of the surrounding buildings, to little fanfare, a victim of gentrification. The neighborhood was changing, the land was valuable, and a large apartment building with commercial space on the first level took its place. That building still stands, and counts among its tenants another Chicago institution, one that mirrors the bric-a-brac aesthetic of the old Relic House, the restaurant RJ Grunts.

The Lind Block

On the 71st anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire in 1942, the Tribune’s “Line O’ Type or Two” column acknowledged what it called the “unknown survivor” of the Great Chicago Fire.

This was the Lind Block, but unlike the Ogden House and Water Tower it was largely ignored in the decades after the disaster.

This is a pity because the Lind Block in many ways would have made a better symbol for the city. True, on appearance it was a fairly ordinary commercial block of five stories on Randolph and what was then Water Street, today part of Wacker Drive, right on the Chicago River.

But the Lind Block took its name from Sylvester Lind, the man who built it in the early 1850s. Lind owned a lumberyard on the site and continued to use the area for that purpose after building the five-story commercial building. He also owned a fleet of boats.

But it’s been reported that Lind didn’t just use his boats for transporting lumber around the Great Lakes.

He was a staunch abolitionist and a conductor on the Underground Railroad. Escaped enslaved people would board one of his boats on the docks near the Lind Block and then sail from Chicago to freedom in Canada.

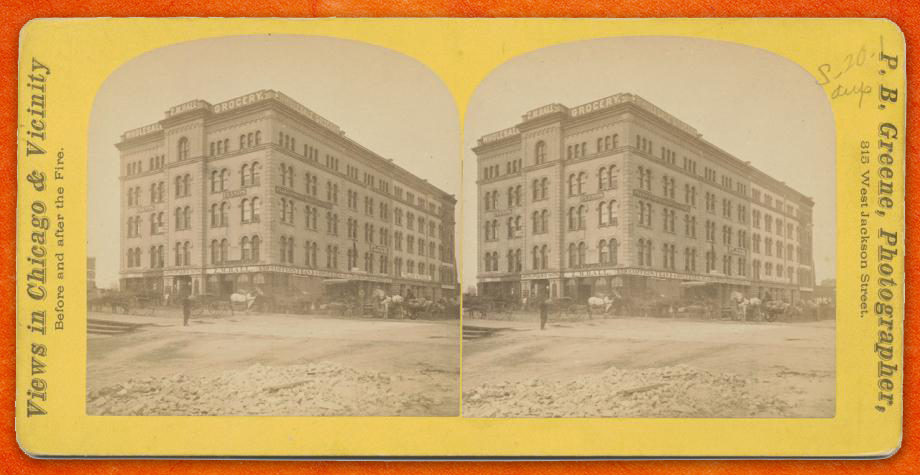

By the fall of 1871, the year of the fire, Lind had sold the building and the Lind Block was leased to ZM Hall Wholesale Grocers, owned by Zebulon Hall.

Like Mahlon Ogden, Hall had come from the East to seek his fortune in Chicago.

When the fire started, Hall’s concern was with his business, the wholesale grocery in the Lind Block. With the help of his two sons and clerks from the firm, Hall fought back the flames.

The Lind Block sat near the river, so water could be hauled up in buckets, and blankets and curtains could be soaked and laid upon the exterior.

As one of the only commercial buildings left standing after the fire, the Lind Block soon became a place of refuge. For three days, Hall gave away what had been in his grocery to fellow Chicagoans made homeless and destitute because of the fire.

A connection to the Great Fire and the Underground Railroad should have made a good case for giving the Lind Block landmark status. Instead, it was torn down to make room for developers coming in to build new construction in the Loop.

In a January 1963 column titled “Oldest Building in Loop Succumbs to Progress,” the Tribune’s Will Leonard lamented the loss of such an important historic building, writing, “snow of 111 winters had melted on the [Lind Block’s] roof, the sunshine of 110 summers warmed its wall. A few years ago, an officer of the engineering firm that owned the oldest building in downtown Chicago said proudly: ‘It’ll be here another 100 years.’ Today they are tearing it down.”

This story was inspired by a question from a Curious City listener.

Paul Durica is the director of exhibitions at the Newberry Library.