In the early 2000s, Jennifer Brandel was working in the media services office of the Bahá'í Temple in Wilmette, Illinois, translating texts about the Bahá'í faith into easy-to-read language. She was struck by one of the texts outlining the group’s approach to learning and service.

“Rather than a religious group going into a community and saying, ‘We know what's best for you, we're going to teach you something,’ they came in with this approach that said, ‘You know your problems best. You know what you need best. I have two hands. How can I be helpful?’,” Brandel recalled.

“They assumed that the people they were trying to help knew what they needed better than anyone else could.”

When she started working as a freelance journalist for WBEZ in 2006, Brandel found herself thinking about that philosophy.

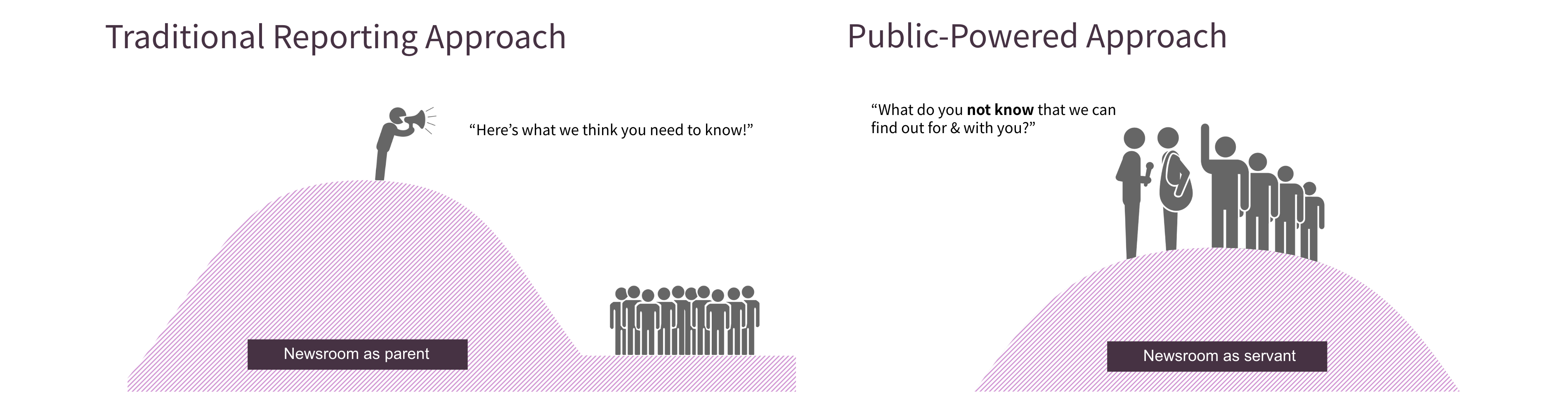

“I thought about what would it look like if journalism started from the same humble posture and asked, ‘What is it that you don't understand, that you're searching for or Googling for? … And how can journalists be a resource to help you get that information so that you can make informed decisions in your life?’”

She started dreaming up an idea for a project that would turn the traditional journalism model on its head: asking listeners what they wanted to know, and leveraging the power of a newsroom to bring them answers. The show would tap the lived experience of the public and involve them in the storytelling process.

The early days of ‘scissors and tape’ (2012-2015)

In 2012, Brandel was accepted by an initiative of the Association of Independents in Radio (AIR) to pilot Curious City at WBEZ.

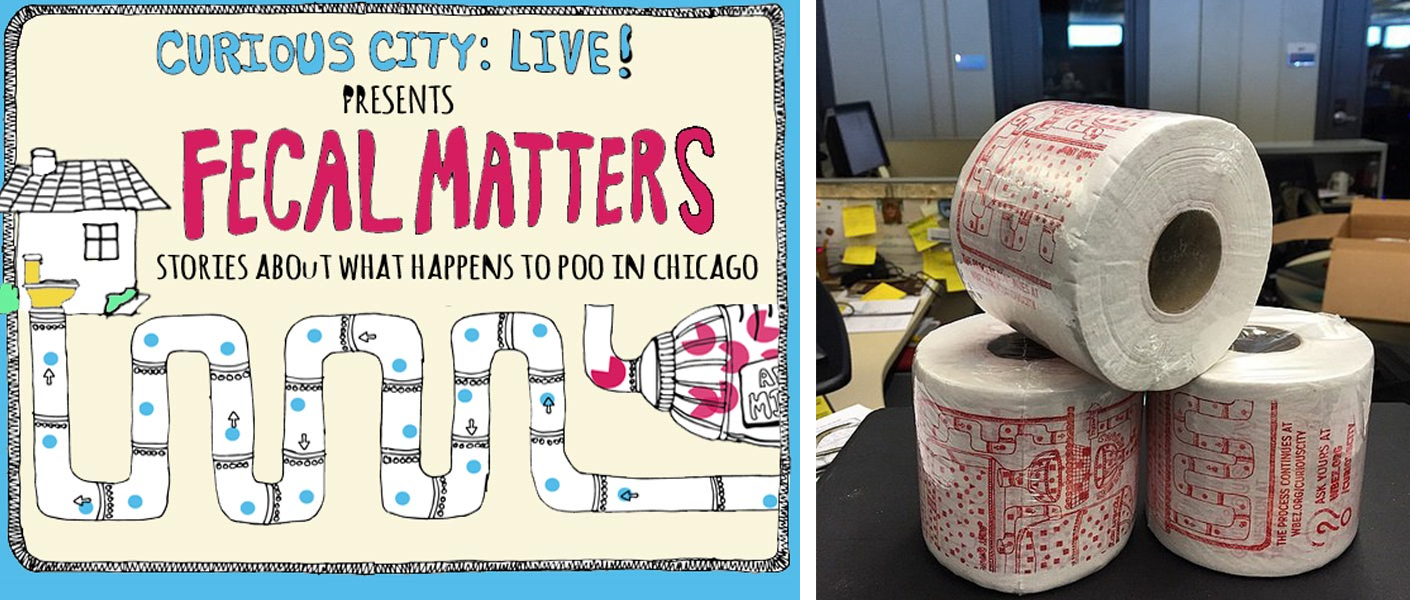

“We called it a news experiment, because we wanted to have the opportunity to really do things that we hadn't tried before,” Brandel explained. “And to just have the liberty to say, Is it a podcast? Sure. Is it an event? Sure. Is it a comic book? Yeah. Why not? Is it a roll of toilet paper that has an answer printed on it? It could be that too. All those things happened, by the way.”

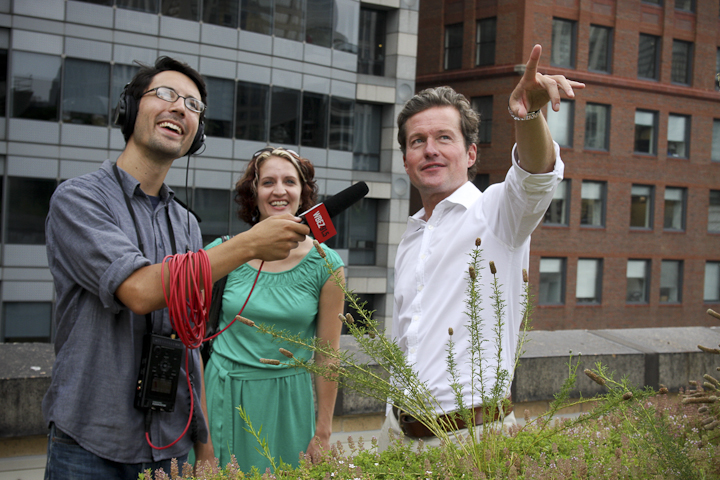

In the earliest days, Brandel, Shawn Allee (Curious City’s first editor) and Logan Jaffe (the show’s first multimedia producer) answered questions about Chicago and the region through live broadcasts, videos, web stories and more on an irregular schedule. People submitted questions through a Google form and questions were stored in a giant spreadsheet. The team took on topics ranging from Chicago’s accents to where your poop goes after you flush the toilet. They also experimented with all kinds of engagement strategies, asking listeners to vote on which questions they should answer and bringing question-askers along during the reporting process.

Jaffe, who started as Curious City’s first intern in 2012 and became a full-time multimedia producer a few months later, remembers the ethos of those early years.

“It was really anything goes,” Jaffe said. “I give a lot of credit to Jenn [Brandel], because she would just think of the wildest ideas. Like for the story about what’s at the bottom of the Chicago River, she had these inflatable kayaks and she was just going to kayak from her house down the Chicago River to Navy Pier — and she did. If your boss is kayaking to work on an inflatable raft for a story, you don’t feel too insecure about pitching your own projects.”

While other shows and reporters at WBEZ had involved audiences in the production process before — from writing personal essays for the annual Chicago Matters series to taking part in listening sessions with reporter Natalie Moore at the station's South Side bureau — Curious City was perhaps the first show at the station to let the audience be the driving force behind every story produced.

“I think the beauty and strength of Curious City has been making that so central to the whole endeavor,” Andrea Wenzel, assistant professor of journalism at Temple University and author of Community-Centered Journalism, said.

In 2015, Brandel was invited to apply to an accelerator program for media entrepreneurs based in San Francisco. “I had the hard decision of: keep going with my absolute dream job at WBEZ … or take a risk and see if I can turn this into a business and help more newsrooms do it,” she recalled.

Brandel chose the latter. She went to California and brought the platform she’d developed for Curious City, which remains the backbone of Hearken’s submission form today: a widget that allows people to easily submit questions on a web browser and a backend system that keeps those submissions organized. Google Forms weren’t going to cut it for a show based entirely on listener-submitted questions; she offered a simple way for newsrooms to do that at scale.

The project got accepted, which helped Brandel receive seed funding and an introduction to the business world, and Hearken was born. Many of its early adopters were, unsurprisingly, other public media stations: KQED and KPCC are two that continue to use Hearken as part of their engaged journalism efforts. (Southern California Public Radio’s VP of community engagement, Ashley Alvarado, is a leading voice on engaged journalism.)

Expanding beyond the ‘public radio listener’ (2015-2019)

As Brandel expanded Hearken, Curious City continued to build upon the model she developed in its early years. However, in 2015, then-Curious City editor Shawn Allee said he noticed a pattern: Many of the people submitting questions were already highly engaged WBEZ members, often from the same neighborhoods.

“The plus is that it got the ball rolling with questions that other people could look to as examples, but the downside is that it pigeonholed the show into a certain type of question and question-asker who was a public radio listener,” he said.

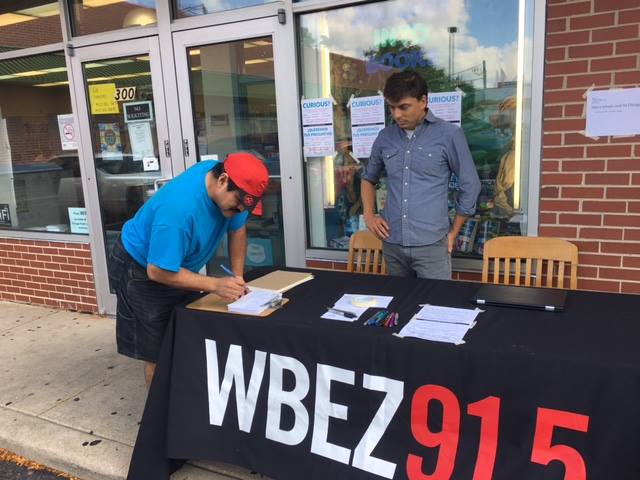

Allee embarked on a quest to revamp Curious City’s outreach strategy to better reflect all of Chicago and the region. He sifted through more than four years’ worth of Curious City questions to understand who the show wasn’t hearing from. He found that the ZIP codes with the least number of question-askers were primarily Black and Latino neighborhoods on Chicago’s South and West sides, as well as suburbs like Cicero, Aurora, Waukegan, and the Northwest Indiana area.

Over the course of 2016, Allee and the team tried various approaches to gather questions from these communities including on-the-ground outreach, question drop-boxes, partnerships with community organizations and social media marketing. Andrea Wenzel closely followed these efforts and documented her insights in this 2017 report for CJR as well as in her book Community-Centered Journalism.

Changing the show’s outreach strategy had an immediate impact. Around a third of all questions from 2016 came from the question-gathering project. Some of the resulting stories include ones about the impacts of pollution in East Chicago, whether the profits from the Illinois lottery actually fund education and why South Side neighborhoods have fewer public murals than North Side neighborhoods. These outreach efforts also led to a live event at the Cicero Public Library about why Chicago has so many rats, where the original question was submitted.

Between 2017 and 2019, the team tried several other ways of bringing stories back to their sources — something Allee said was a persistent challenge for them. In 2017, a question about whether Arab and African American Muslims worship at the same mosques inspired a panel event in partnership with the American Islamic College (AIC) that dove deeper into the roots of division within the community. There was so much audience interest and participation at the panel event that Curious City and AIC partnered the following year to co-host an interactive workshop on building stronger interracial relationships in Chicago’s Muslim community.

The strength of one-off events like these was that by popcorning to locations around the city, the team could collaborate with a broad diversity of people and answer a wide range of questions. But one of the drawbacks was it was difficult to develop a sustained relationship with any one community. The anxiety at the heart of this approach was that if you try to serve everyone, you might end up serving no one.

What’s next for Curious City?

In the past few years, the team has tried new, sustained ways of reaching and serving communities that weren’t already Curious City listeners.

“We knew from the beginning that any reporting we did, we would bring back to the community,” said former Curious City editor Alexandra Salomon. “That was the strategy from the get-go.”

Even when spending several months in a neighborhood at a time, aspects of this approach can still be inherently problematic. A reporter or producer who doesn’t live in the neighborhood asking longtime residents what questions they have about the area can be met with the legitimate reply, “Why should I be asking you?” It can also inadvertently prioritize a flaneur-like attitude of wonderment or naivete, and exclude questions or observations that come from people who already know their neighborhood deeply. This is one of the reasons working with trusted community organizations has been essential to the Neighborhood Series — as has being flexible around what constitutes a Curious City-style question.

Jaffe, Curious City’s first multimedia producer, said a shift she’s noticed from the show in recent years is a move towards making more room for serious stories. “We don't have to always rely on these quirky questions or stories to stand out,” she said. “The principles of the project are enough.”

Looking back on her time with Curious City and Hearken, Brandel said one of the things that’s been most heartening to her is the attitude shift she’s seen across different newsrooms towards readers and listeners. “At the beginning,” she said, “most people were kind of thinking, Do we really want to involve the audience? What if they ask bad questions? What if they come along with us and compromise a source?”

“[But] people are amazing,” she continued. “They're curious, they are humble, they are excited to get the opportunity to learn what goes into reporting and also to understand how difficult it is … There's a lot of rigor, a lot of work and production involved, even in a two- or three-minute story.”

In keeping with that spirit, we’re giving the last word to a few Curious City listeners whose questions have inspired stories over the years:

“Your journalist not only validated my question and did his best to answer it, but also encouraged me to act on his findings. He treated me like an intelligent person with individual agency versus a passive consumer of news.”

“What I deeply admired was that Curious City said, … ‘We hadn’t considered that. Might we interview you? We want to remedy this.’ A lot of places won’t do that. … I love the respect I hear, and that you take your questions seriously.”

“Being involved with Curious City totally changed my outlook. Curious City answered my question, but that meant the ball was in my court to keep advocating for the type of environmental changes that a lot of people want and deserve.”

What do you want to hear about in the next decade of Curious City stories? What should we keep doing? And what can we do better?

Adriana Cardona-Maguigad is Curious City’s reporter. Follow her @AdrianaCardMag

Joe DeCeault is a senior audio producer for WBEZ. Follow him @joedeceault

Katherine Nagasawa is an independent producer. Follow her @Kat_Nagasawa

Maggie Sivit is Curious City’s digital and engagement producer. Follow her @magisiv